Last month, ESPN ran a story about 18-year-old Pistons rookie Jalen Duren playing against LeBron James for the first time. “It'll be like a surreal moment, you know what I mean,” Duren said. “To be on the floor with him is legendary in some way. It'll be a cool experience.”

I can relate. To be on this website with Sabrina Imbler is legendary in some way, and indeed a cool experience. I’ve admired their science writing for several years, and so have my colleagues; it was not uncommon for Defector writers to Slack each other “new Imbler banger just dropped!!!” or “Sabrina alert!!!” whenever they published a new, reliably fascinating, perfectly headlined creature story at The New York Times. I could not have imagined, one year ago, that we'd eventually bond over seeing the same bear in a forest. But earlier this year, Tom Ley came to us with the coolest Sabrina alert!!! of all time: Sabrina was going to work here, at Defector! Subscribers have no-doubt enjoyed their work on the creature beat, which is eclectic but driven always by a desire to better understand those little guys around us.

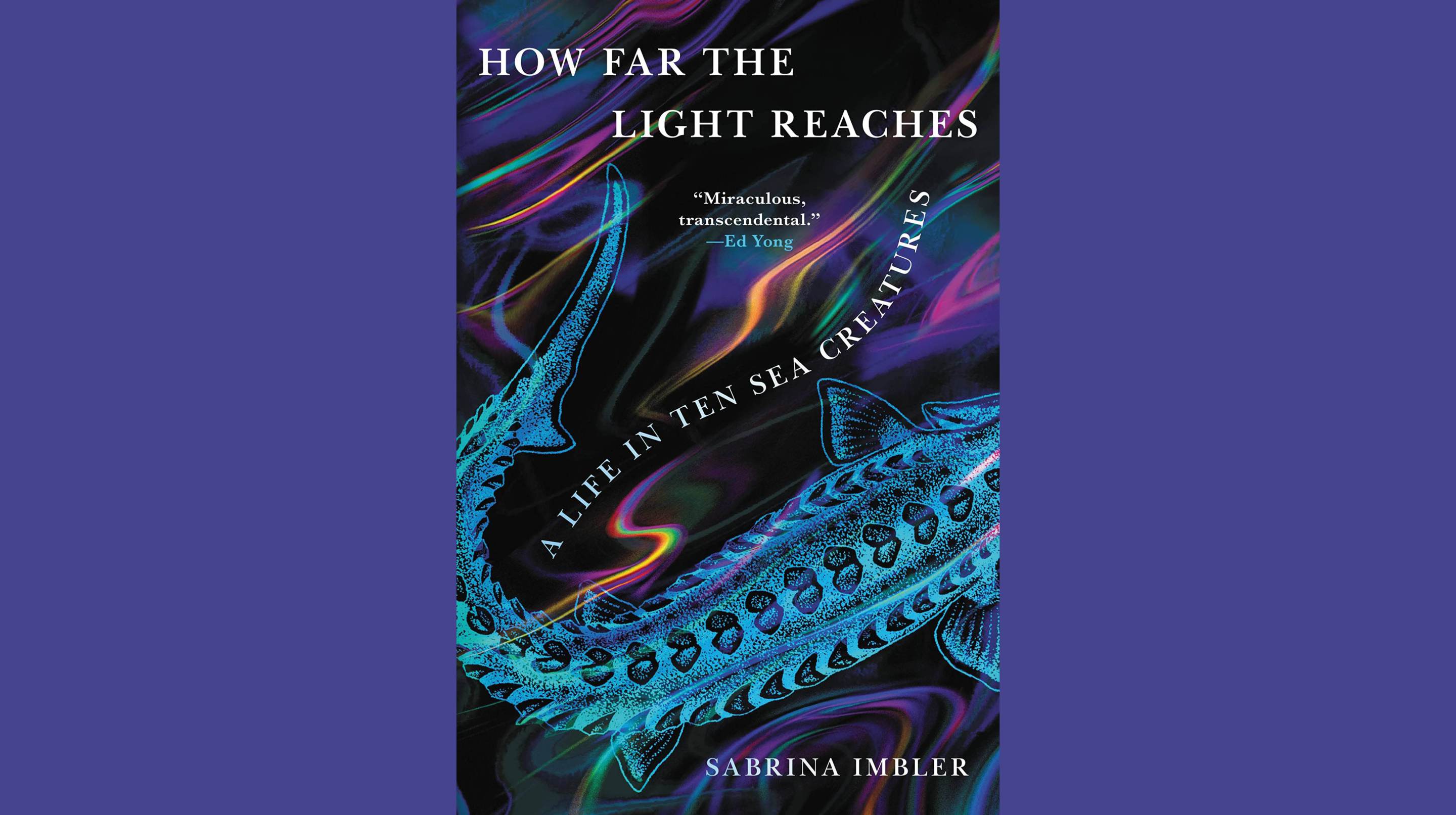

Now it's my pleasure to tell you all that a new Imbler banger just dropped: Sabrina has written How Far The Light Reaches: A Life In Ten Sea Creatures. The book's tender, stunning essays treat humans and creatures all with the same curiosity, contemplation, and care. Sabrina introduces readers to the creatures that pushed them to "envision wilder, grander, and more abundant possibilities" for their own life. In my personal favorite of the essays, about the beadlike and gelatinous and chained-together salp, for whom "home is the rest of its salp," Sabrina writes about the queer history of Riis Beach and the joys of swarming together, in community: "Slow and steady, say the salps. It doesn't matter how fast we go, only that we all get there in the end. We may all move at different paces, but we will only reach the horizon together." Last week, I called up DEFECTOR'S OWN Sabrina Imbler to chat about their singular writing style, the "unexpected poetry" in scientific papers, and their work to find points of connection with creatures. How Far The Light Reaches is out today.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity and, if you can believe it, to make us sound even more charming and wise than we both already are.

The most interesting thing I learned in this book is that your mother is from Michigan. I'm going to count you as a member of Michigan Slack.

Thank you. Have you been to Hancock?

It's in the Upper Peninsula, and I've never actually been there. But it seems nice. A lot of Finnish people live there, I think.

I guess maybe that makes sense if you want to live in, like, the Finland of America. From my limited knowledge of what Finland is like.

I've never been to Finland either, so I don't know. I’ll probably sooner go to Finland than to the Upper Peninsula. You explain a little in the acknowledgments, but I would like you to tell me about the title of the book.

The title came very early in the process because I was trying to pitch the book, and you need to have a title to pitch the book. I had written a chapbook that I titled based on the Wikipedia article; on Wikipedia, they'll have disambiguation pages with all the different meanings. It was really fruitful for that project. So I was like, let me go back to Wikipedia. I googled, I think, “ocean.” I went on Wikipedia for “ocean,” and just kind of read the whole thing. There's one phrase that was like, the ocean is divided into different zones based on how far light reaches. I was like, that’s a stunning phrase, let me lift that. At first I was drawn to it for aesthetic reasons, but every title I tried that had the word “sea creature” or “ocean” felt very popular science-y. And I didn't want to take readers by surprise, who wanted a very straightforward explanation of different sea creatures. It was sort of a gem on Wikipedia that I really, really liked.

Ah, I love that story. You're very conscious in the book about where you want to shine the light—about the nature of personal writing and some of the trade-offs and considerations you have to make. There was a line I liked: “And this is the part where I might tell you how my parents met—but I don't want to, because I have to keep some parts of my family to myself.” I suppose this is the ultimate personal essay question: How do you decide what parts to keep to yourself when you're writing?

I went to college in the time of the confessional trauma essay. I would read things on xoJane and Jezebel, and I really thought, that's my ticket into writing about myself and that's the only way to do it. The version of myself that pitched the book I think imagined it would take that form of, here's all of my trauma, here's every possible bad thing that has ever happened to me and let me digest it for you. I feel really grateful that I missed every single deadline I had for the book and allowed myself to just grow up a little bit as a person. In the process of writing it, I became a better writer and I became a better journalist. I read all these interviews with David Sedaris, where he's like, “My family hates me because I'm writing about them.” And I don't want that. Like, why are you sharing that? I want to be cognizant of what I share and what is mine to share and what is not mine to share.

For essays that really heavily involved someone else, like the essay about my mother—my mother from Michigan—I shared a doc with her and we talked about it. I was like, I give you full veto power, if there's anything here that you don't want to be in here. She was incredibly generous. It was a really generative conversation because she also pointed out, "Oh, this is how you remember this, but this is how I remember this." And so it was this exercise in what is actually true. These are two memories of a situation that is kind of unknowable and we're going to come the closest that we can to it.

I was nervous about writing a memoir, because I'm young, and I haven't really lived an interesting life, and people are going to find this boring. But I feel like the only ethical way to do this is really to try to focus a lot of the personal stuff just on me. And to ask permission for other people's stories to come in, and if they say no, then I respect that. I went through the final draft several times, and just sort of cut details where I was like, this kind of makes me feel weird. I'm just going to cut it. And so I did several rounds of like, what personal things can go? And if they can, I will cut them. But it's still a very personal book.

So what is that experience like—deciding to ask for permission rather than forgiveness from everyone who knows you, so they don’t all David Sedaris-style hate you? Were you nervous?

Yeah, it was frankly terrifying. I talked about it in therapy. I sent these deranged emails to my friends who had significant and also completely "I mentioned you in one line" roles. I thought that everyone would be like, "I hate this and how dare you." It was cool to see people say, "Oh, yeah, I remember that too. Of course you can put that in." But I was really, really dreading the conversation with my mother. And I'm ultimately so glad that I did talk about the essay with her. It's been like, maybe I should have talked about stuff more instead of processing the trauma alone and then writing a whole essay about it. What if I just raised this in a casual conversation? So I'm still growing up.

Well, there would be no good writing if we just talked about things and processed them normally.

Yeah, if we were all healthy.

Something I noticed throughout the book is how perceptive you are about the way you used to talk about yourself or used to tell stories about yourself—the presentation. The first essay begins, “The truth is that I was asked to leave Petco, but I told everyone I was banned." Later, you call this your "origin myth" and "designated fun fact." There's also your essay on hybrids, which lists different scenes and beginnings and endings the essay had once included but doesn't anymore. What do you think has changed about the way that you talk and write about yourself? And what might change in the future?

In the process of writing the book, I realized so many of my formative stories that I would tell, I was more interested in the story being very interesting so that I would appear funny and cool. So many of these crucial moments in my life, I sort of repackaged into things that I can present to people so that they will like me more, and that is mortifying. I've been questioning, why has it for so long been my quest to be liked by people? It was helpful in terms of growing as a person because you revisit these stories and try to excavate, what is the actual truth of it? What is the meaning that this has for me, just in this hermetic chamber, outside of how I would want to tell other people about this.

It has taught me to be more rigorous in how I try to understand what has happened to me but also to be more gentle with my past self and to try to be candid about why I made the decisions I did or why I reacted in certain ways. My editor, several times, would be like, "You're being so harsh on your 17-year-old self. You couldn't have known everything." And I was like, oh, yeah, that's such a weird expectation that I have. Just trying to treat myself with more care has been a big lesson.

Some of the writing about nature that I read can sort of tip into this overly romantic register. And I wonder if, in doing so, it has the effect of distancing humans from creatures. So I appreciated your really visceral, even gruesome descriptions of things. I'm still haunted by the image of a mother octopus in her "death spiral" after brooding eggs. ("Some even begin devouring themselves, tearing into the tips of their tentacles like they would a crab.") I wonder if that's something you ever think about when you're writing creatures and thinking about how we should relate to them.

I want to ask, when you say “romantic,” what is that?

Hmm, maybe that creatures are so peaceful and live these simple, ideal lives.

If you're in a similar project, and you're looking at an animal to be like, what does this tell me about myself? or what point of connection do we have?, I think it's really easy to pick the obvious ones. Like, we both grieve, or whatever, and then to dispense with everything else. But that feels like a really limiting way of finding connection with animals. And there are so many things that they do that are strange and incomprehensible, and have no parallel or connection with us. The death spiral— it's not this octopus wanting to kill herself. That isn't true. It's just a fundamental biological process that octopuses experience, and it is so different from the way that we experience life. But still very fascinating and unsettling.

It can be a good practice to sit with unsettling or strange or kind of incomprehensible practices that animals have. And to be like, this is just another way of living and this isn't better or worse than the way that we live on Earth. Just exposing yourself to the diversity, and to the often gory ways that animals live and eat and reproduce and die. I tried to be clear in the moments of the book where I was sharing this part of this animal story to draw a very clear connection between my life and this creature. There are other moments of "Here's this thing that I learned and I have to share it, because it is just wild."

Did you find it difficult ever to resist the obvious connections? Or really, what goes into writing one of these essays? Do you start with your life? Do you start with the creature? How do the two meet?

I wish I had a formula, but it really was kind of random. The first essay to come out of the book was the octopus essay, where the parallel was very clear: This mother octopus, who isn't eating, to protect her young, and my own mother, and our shared relationship with disordered eating. That was the first essay that I wrote. And I liked the way that the story sort of braided together. So I was like, what else? What else would work? I made this chart of sea creatures in one column, and then my life in the other column. Very elementary school, but it was helpful to see things in my life that I would be interested in writing about and creatures I think are cool. A lot of connections didn't make sense, but I think it was just helpful to see them as things that can be in conversation with each other.

2017 goals pic.twitter.com/OnHcsltJub

— Ryan Broderick (@broderick) September 13, 2016

Some of the essays started in very obvious, literal places. I saw this meme of the Yeti crab that was like, "This creature has adapted to the crushing pressure and oppressive darkness." And I was like, I can relate, I'm going to use this crab to write about living in Seattle, a place that I hated. And then once I started to write about the crab, maybe I just got lucky, there were so many resonances that I felt like I was able to to excavate. That's how the essay became about your nightlife and thinking about hydrothermal vents on the bottom of the sea—these really are oases, and what was my oasis in Seattle? I learned about the species of Yeti crab that literally dances by these hydrothermal vents, and I was like, IT'S ALL COMING TOGETHER. But then there were other essays that I tried to work on. I had this essay that I pitched that was about Guy Fieri and sea slugs, which was like, "This sea slug looks like Guy Fieri to me." And then I tried to write it and it was the worst essay I've ever written. I was like, I have to cut this. If there's a connection here, I trust myself to not push it too hard. It's OK to try to find the connection, and also to be like, nope, this isn't working and I'm gonna delete.

[After our interview, Sabrina kindly shared with me the Guy Fieri sea slug. Check this guy out! That’s one Guy Fieri-ass sea slug! And sign THIS petition to demand Sabrina release the unpublished Guy Fieri essay on Defector dot com NOW!!!!]

A strength of all your science writing, and not just in this the book, is language that’s so fun and evocative and poetic. Do you ever have trouble doing that and also getting the science right and being rigorous?

Definitely. The person I want to shout out is my fact checker, Hannah Seo, who is just a genius. I always knew that I wanted to get the book fact-checked. I also was trying to find a fact-checker who wasn't just a science journalist, but someone who could sort of play with an appropriately literary way to talk about this. I'm sure a very stringent fact-checker would take issue with some of the ways that I write about things. And that's fair. Hannah and I tried to hash out, what is a fair stretch? Is this poetic language used for a greater purpose? Does it illuminate something? Or are we just describing something imprecisely? It was really helpful to have that partnership in approaching the book. And it was also really hard, because the most important thing to me was getting the science right. Oftentimes, I felt like I had to write it very clinically at first to make sure that I was understanding the process that I was describing, or the biological phenomenon. Then I would be like, OK, now that I feel like I get this, I can sort of tweak.

Scientific papers can have a lot of unexpected poetry in them. I was really struck by this paper that I was reading about—I think it was called, like, "questioning the rise of gelatinous zooplankton in the Anthropocene," or something very clinical. But it was basically, all these reports are saying there are so many jellyfish, so many creatures that are gelatinous, drifting through the water. All these reports are saying they're increasing in huge numbers because of climate change. And while that is true, we also want to point out the fact that these creatures weren't sampled very well, historically. How much of this is we're just finding them because we're looking for them and how much of it is they're actually increasing in numbers? The authors of that paper, the language that they use, it is so resonant with the ways that I've read about queer history and trying to find stories that weren't recorded or were purposely obscured. A lot of papers, I didn't really have to tweak much. I could take what the authors were saying, and just put it in this new context. And it felt poetic in a new context, but it was really just how they were describing it.

A few years ago, I read one of Rachel Carson's books about the sea. There's this wonderful chapter about how the moon was formed. It’s really beautiful. And then later, I found out that it’s completely wrong. It wasn't her fault. Science just advanced past that understanding of the moon's formation. I was pretty crushed, but I guess everything is always evolving.

The book is fact-checked and we did have a very intensive process, and also, I'm sure that in a year, they will make a discovery, and I'll be like, well, OK, sorry.

Yes, in 50 years, some teen will find your book and think it's awesome, and then be devastated to learn that all of it is fake.

And I hope that teen is in Michigan.

Something you write so well in this book and in your work for Defector and in your work before—are these little gems of comparison. The book is filled with these. I picked one essay, and plucked a few just within the span of a couple pages. This is from your essay on the octopus: “In the bright beams of the submarine, the octopus’s edges glowed the reddish purple of a salted Japanese plum.” Or “when the octopus held herself close in this way, she was around the size of a personal pizza.” Or “the tattered egg capsules still clinging to the rock like deflated balloons.” Does that language come naturally to you? What’s the process of crafting the right metaphor?

Thank you, I'm happy that you liked those comparisons. The octopus essay really just hinged on a couple of papers, but primarily this one paper about this specific octopus. So I'd spend long stretches just looking at the photos of this particular octopus, because they really are the only images that we have of this one that I was writing about. I wanted to be as precise as possible. I was reading a lot of the news stories about it, and they're all like "purple octopus, purple octopus." Then I looked at the images, and I think I was imagining this octopus being so purple. But there are so many different kinds of purple. What is the precise shade of purple? I remember spending a really long time just looking at different purples to be like, is this purple right? And I'd be like, oh, this purple isn't quite right. And trying to find a purple that was specific enough to sort of like conjure a specific hue, but also recognizable enough that people would know what that is. Or even if they don't know, it conjures like something for them. And then when I looked at the octopus's diameter—it's really hard to find size comparisons on the internet, which is frustrating. I wish that there were better options.

It really does not come easily or naturally. It's kind of just me googling a bunch of different things, trying to find like, how long is this seed? I'm always trying to find out what the size of a kernel of corn is. And the result will always be for an ear of corn. I want the kernel! So yeah, it was a harrowing Google experience to find those comparisons.

We need, like, a database of dimensions of things for you.

Exactly.

It seems like a lot of them are food comparisons, which I appreciate, as most of the objects in my life are foods.

There's a whole trope in science journalism of "as long as a deck of cards" or "a football field" or "the size of an Olympic swimming pool." And I guess because I'm describing creatures, they're generally not the size of a football field. Maybe my mind is just like, what is a pleasing thing that people could encounter? It's a cantaloupe. It's a jug of milk. It's eating things. Chewing foods.

Well, not to be rude, but I'm sort of relieved that this does not come naturally to you. Because if it did, I would be very envious. They're all great.

I wish I had a database of sizes. I like having an Excel spreadsheet where I put—whenever I use a size comparison, I put it in here. So I don't come back to things. Because sometimes it's so specific. In one of my stories at the Times, I described something as the size of a stroopwafel and I can't do that again. Nothing else can be that size. But for corn or a sesame seed, sometimes that's the best thing to use. I don't know if I'll use personal pizza again. It's a good size.

I liked personal pizza! And I remember reading stroopwafel. Do you ever put things in the spreadsheet to use for future comparisons?

Oh my god, that's a really good idea. I don't, but I really should. I should bring a little pocket tape measure to restaurants.

You're comfortable writing in that granular sense, with a close lens on one particular creature. But I was also interested in the way you could zoom out at the field more broadly, to look at who has the power in science research. There's a story about a giant worm with powerful jaws, the sand striker, which was first kind of cruelly named after Lorena Bobbitt, a victim of abuse.

When I first started writing the book, I thought that it would just be like, here's me, and here's a creature and it's just us. A lot of popular science says to tell the story of the creature, you also have to tell the story of the scientist. And so many of those scientists are white men, and I didn't really know how much they should factor into this book. But there were these moments where it's part of the story, and so I had to tell it. The Bobbitt story I actually reported on when I was at Atlas Obscura, about the push to rename the worm the sand striker. I had interviewed the guy who originally named it and he was, I think, very upset with everyone blaming him for naming the worm this. He was very resistant to being interviewed and it was this moment of this reckoning also happening in the sciences. There are all these different layers of people who are being accused of sexual assault and people who are just sort of upholding this culture or making jokes of survivors.

And so, when I first started writing the sand striker essay, I really thought it would just be about the worm and me. And then I was like, no, of course, this is also about people. With other stories, like the hybrid essay, I also didn't really think that the scientists who discovered the hybrid fish or who described the hybrid fish would really factor into it. Then I read about them, and was like, well, now that I have this information, it feels weird to not include that. There were moments it felt impossible to extricate a creature's story outside of the realm of science and the scientists who made this discovery and decided how this would be named or how this would be shared or how this would be chronicled.

Before we wrap this up, is there anything else you'd like to tell our readers?

Wow. There isn't lot of poop in the book. And I apologize for that. I'm honored that anyone would read it. But especially honored that DRAB and my coworkers would read it.

Thank you for writing such a wonderful book. And we are all very proud of you. I will transcribe this and post it Tuesday...and sales will skyrocket as a result. Just warning you.

Instant bestseller.

We're like, you know the Reese Witherspoon book club sticker at bookstores? We should actually get a little sticker.

Like a physical sticker.

Yeah, like the Oprah one or whichever George Bush daughter has a book club. She's got a sticker. I'm going to look into getting a sticker for this.

That would be super cool. And then we can retroactively sticker them.

I’ll personally sticker all of them myself.

“You’re defacing our books!” No, we’re improving them.