About the most that can be said for Donald Trump, as a politician and as a person, is that he didn't let being President of the United States change him. This is not really a compliment, to be clear. Trump's public persona was grandiose enough that he tended to talk about becoming president as if it was something like a demotion, with him benevolently stepping away from his job as The King Of Success and his wonderful life enjoying the finer things alongside the most powerful and influential people to do the world a favor. If he was awed by the power of the office at all, it was mainly in the same way that he would previously have been impressed by particularly large slabs of marble, or the number of models in attendance at an associate's birthday party. He certainly never let the immensity of all that responsibility push him to work any harder; the fantasy that Trump would rise to the moment, which persisted in the elite echelons of the mainstream media through a poignantly long series of entirely unmet moments, was not so much misplaced as it was a category error.

This is what I mean by Trump not letting the pressures of the presidency change him. That stuff could not go to his head, because he considered such things below his customary level of glamour; they did not cause him to alter his behavior in the least because his behavior is all he is. His post-presidency has been similar to his presidency, which was from one moment to the next identical to the decades that preceded it. He watches television and gets upset about it; he gossips and gripes; he eats the biggest and most beautiful piece of chocolate cake you've ever seen. During the years that Trump was president, he really was as impervious as he has always believed himself to be. This wasn't really much of a change, either, but it would necessarily make it more difficult to accept consequences when they arrive.

In the recollections of the various operators and strivers and morally malleable retreads and aspiring genocidaires and off-brand Beltway reptiles and innumerable lawyers whose paths crossed with Trump's during his time in power there is almost always some moment when they awaken to the fact that the person they are talking to, who is beloved by millions and temporarily the most powerful man in the world, is not just a blowzy weirdo but a fucking dunce. It's not like these people were there because they believed in him, although there are a few of those; these people are all, in varying ways and to varying degrees, amoral opportunists who thought that they might be able to get something from Trump, and that helping him do whatever it was that he wanted to do at that moment might help them get what they want, down the line. Many of them surely knew that Trump wouldn't do anything to help them on purpose. The ones that actually believed in him seemed to love him precisely because of how selfish and cruel he was, and saw it as aspirational; the rest realized that he was world-historically distractible and, again, kind of a dunce, and figured that they might be able to get theirs while his attention was elsewhere. It is America's strange blessing and profound damage that it keeps producing more and more people who believe that this sort of thing might work for them, which it never does. Mostly, these people just have to spend their time in his service having interactions like this one between Trump and one of his lawyers, which the New York Times reported last week:

Mr. Corcoran describes meeting Mr. Trump at Mar-a-Lago last spring to help him handle a subpoena that had just been issued by a federal grand jury in Washington seeking the return of all classified material in the possession of his presidential office, the people familiar with the matter said.

After pleasantries, according to a description of the recorded notes, Mr. Trump asked Mr. Corcoran if he had to comply with the subpoena. Mr. Corcoran told him that he did.

That Trump did not follow that advice is only part of what makes the multi-count federal indictment of Trump and a former aide that was handed down on Thursday evening and released to the public on Friday such delightful reading. Trump is just not a guy who likes paying retail, and there's a strange sort of comic tension to watching him confidently and repeatedly try to Do Deals with the increasingly unamused representatives of the FBI vis-à-vis his repeated and unambiguous violations of various federal laws. This comic thread, which was sometimes much easier to laugh at than others, ran throughout Trump's presidency and post-presidency—when he was upset, which he almost always was, it generally stemmed from his blithe, instinctual disregard for the idea that any objectively major national concern or red-letter law could matter enough to even momentarily inconvenience him.

Which maybe oversells things somewhat. The indictment notes that Trump told his lawyers to lie to the FBI and a grand jury, and had his aide hide from the FBI various documents that it sought, and repeatedly suggested holding back or destroying various documents that he had brought from the White House to the Florida banquet facility and event space in which he now lives. "The classified documents Trump stored in the boxes included information regarding defense and weapons capabilities of both the US and foreign countries, US nuclear programs, potential vulnerabilities of the US and its allies to military attack," the indictment notes. That all sounds bad.

Again and again, though, the indictment doesn't so much undercut the significance of that badness as recontextualize it relative to Donald Trump doing the only things that he ever does. Breaking laws in an oafish, overt, seemingly arbitrary way is absolutely Some Donald Trump Shit. But what Trump was doing with all those secret and confidential documents, the indictment reveals, was also Some Donald Trump Shit. While he is certainly one of the most bribe-able individuals of his generation and unquestionably unbound by any higher or finer concerns whatsoever, and while that would not really be the sort of person you'd want having a bunch of sensitive documents in their possession, it is equally salient that Trump is fundamentally an absolutely whopping baby whose deepest personal desire and abiding life's passion has always been showing off in weird ways and pursuing vinegary personal feuds.

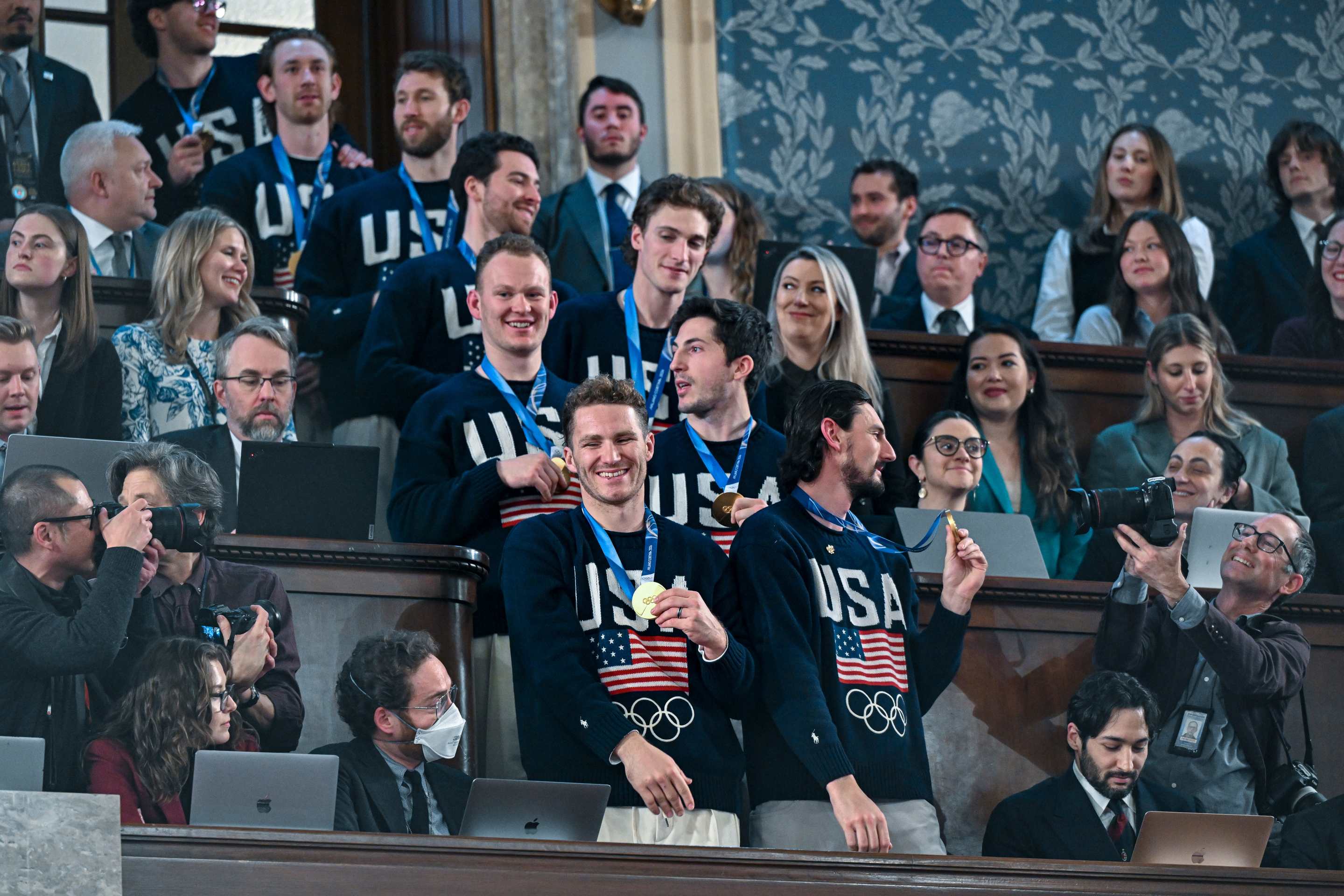

The indictment bears this out, too, revealing that Trump mostly used those highly sensitive documents—which he knew it was illegal for him to possess, and which he was actively hiding from the FBI—to impress upon people visiting him in his quarters at that banquet facility/event space how important he was. The indictment shows Trump shuffling through a stack of papers in front of some people ghostwriting the autobiography of one of his former Chiefs of Staff to prove a point about how dishonest and unfair a third person, unrelated to the subject of that autobiography, was being about him. Trump shows a classified military map to a member of his Super PAC but tells him "not to get too close." Boxes of paper are stored in various demeaning places, with more or less the same care that my parents display for their bulk purchases of paper towels. The aide who was indicted alongside Trump at one point discovers boxes full of folders marked "secret" that had fallen and spilled across the floor in a storage room, and then sends two photos of the damage to a fellow aide, who replies "oh no oh no." The boxes were stored in showers and basement storage rooms and hard by the toilet in a bathroom that also had a chandelier in it and across the part of a ballroom stage where a wedding band might later set up its monitors.

I know nothing sums up the presidency better than the McDonald’s feast photo but this is getting close pic.twitter.com/g8IA8YX9Ez

— Patrick Monahan (@pattymo) June 9, 2023

As part of the extremely calm defense that Trump posted on his personal social media platform, he described the (many) such documents that "the Gestapo" discovered, and which he had denied having, as "just ordinary, inexpensive folders with various words printed on them, but they were a 'cool' keepsake." This is not a workable legal defense, but taken altogether it's tempting to give Trump the benefit of the doubt on it. Whatever specific secrets might have been in those folders—the "various words" printed on them—clearly didn't matter very much to Trump, or anyway didn't matter as much as the fact that he considered them his to keep, and periodically wave around in front of whatever Palm Beach real estate dingleberry he was aiming to impress at that moment.

This, too, is authentically Trump. The club in which he lives fills and empties every day like a gilded, laboring heart; passing through it are people who, for all their differences, share in common the decision to have paid Donald Trump many thousands of dollars a year to hang around him and eat fancy-style food from 1989. If that is all Trump knows about them, it is also all he needs to know—the thrice-divorced orthodontists, the socialites and realtors all stretched and poreless and uncanny in their pastels, the plump yacht flotsam and incredibly racist Europeans claiming some vague royal lineage and the bristly young sociopaths on the make are all marks. Trump holds them in low regard as such, although he's happy to take their applause and money when it's offered. He knows that they want something from him, or believe that they can get something from someone else simply from being around Trump; he knows, too, that his status as a past and possibly future President of the United States is a big part of that appeal. But this is another way in which the job never left a mark on the man—that status still wouldn't feel real, or sufficiently his, unless he had some props around to sell it, and some, any, secret to wave in front of his guests and then keep as his own.