The year 1999 tends to be remembered as a banner year for American cinema. That was when we got The Matrix, Fight Club, The Blair Witch Project, and many other memorable films. It’s also the year that an hour-long animated children’s film called Our Friend, Martin came out.

There was a ripple through the classroom whenever our grade school teacher dragged out the “educational” videos in lieu of a proper lesson—excitement because it meant we probably didn’t have homework and didn’t have to listen to something tedious; dread because it was almost always something we’d watched a dozen times already. Our Friend, Martin was strange. It followed two middle school boys—one black, one white—who travel back in time and talk to Martin Luther King Jr. after a magical encounter with his watch in a museum. Every now and again, the boys jump forward in time: Martin at 12, Martin at 15, at 27, at 34. In each instance, King exposits the racial state of affairs in America, a lesson imparted to the audience through the boys. What’s interesting about Our Friend, Martin is that many of these sequences were blended with actual footage of the time. In one scene, the boys witness the 1963 Birmingham riot, black-and-white footage of Bull Connor directing cops to hose down bystanders spliced with full-color cartoons ripped from a kid’s book. The method was heavy-handed but effective; even now, Our Friend, Martin maintains a frankness about racism that’s surprising. Later in the movie, the boys try to go back in time to prevent King’s assassination, in the process turning the future into a racist hellscape. The implication is that, without King, without the work of a single, exceptional person, America would have descended into a fascist, even more deeply segregated country. It’s a kid's movie. There are worse ways of getting the point across.

I thought about Our Friend, Martin often while watching Ava DuVernay’s Origin, a film inspired by the book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent by journalist Isabel Wilkerson. Specifically, I thought of the drawbacks of didactic filmmaking that, unlike children’s educational programming, aims to teach adults a simplified lesson.

If one were to watch Origin having no familiarity with the source material, one might mistakenly end up with the impression that Wilkerson’s book is a memoir rather than a mainstream journalistic sociological study. The film follows a dramatized version of Wilkerson, played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor, as she tries to formulate the socio-historical theory of everything that underpins her book. What unites the racist oppression of black Americans to the genocidal targeting of Jews during the Holocaust? How might this relate to the Indian caste system and the hierarchical segmentation of Indian society? Ostensibly, Wilkerson’s journey is one of complication. Her argument is that “race” can’t remain the coverall for instances of bigotry that transcend socio-economic and ethnic boundaries. “We call everything racism,” Wilkerson says in the film. “What does it even mean anymore?”

Starting from this supposition and treating it as a layered, robust intellectual throughline of the film might have rendered Origin coherent and compelling. But DuVernay has no interest in presenting novel evidence for her audience to ponder over, and no compunction to allow the very theory she’s dramatizing to penetrate the aesthetic underpinnings of the film. Origin isn’t homework; it’s too pre-digested for that. Because the film is also a hagiography, it indulges multiple, prolonged sequences wherein Wilkerson’s personal struggles—chiefly, the one-two punch of her husband and mother’s death—are supposed to illustrate some inner fortitude and brilliance that DuVernay assumes is already obvious—it’s an accelerated version of A Beautiful Mind’s condescending portrait of genius, without the floating equations or discovery.

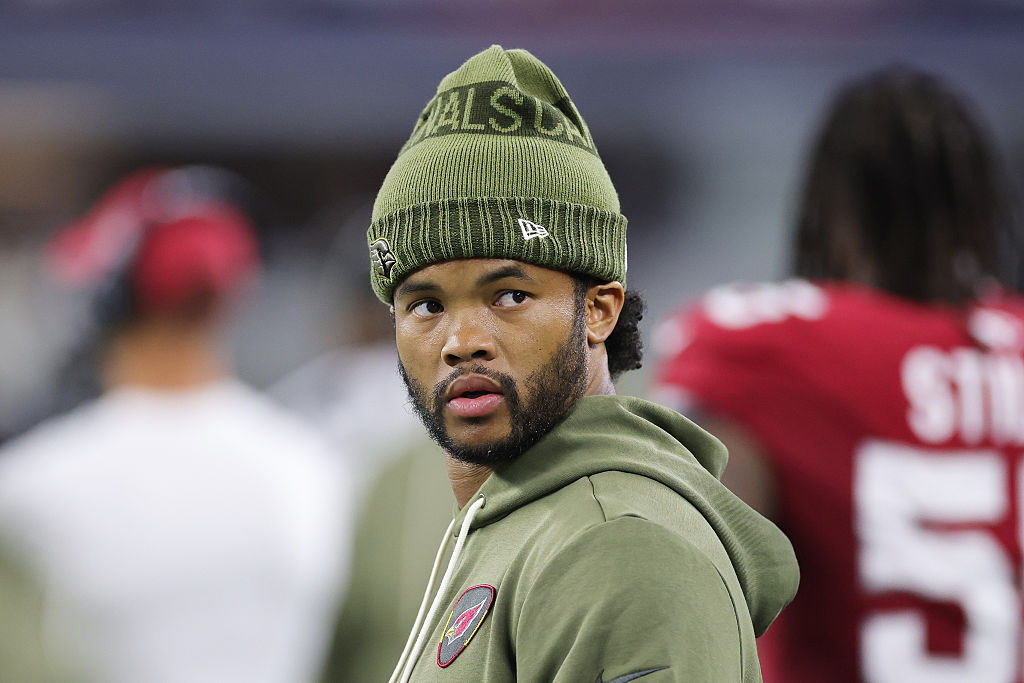

Origin’s opening sequence goes some way toward describing the film’s project as a whole. The movie starts with a dramatic portrayal of the killing of Trayvon Martin. In effect, Martin’s death acts as the catalyst for Wilkerson’s investigative journey. It’s through the intersecting factors of Martin’s place, time, and circumstance that she’s pushed to try and find a method for divining a more comprehensive understanding of oppression. DuVernay is a filmmaker interested in capturing texture and tactile warmth, and in those opening moments she uses those elements to create a feeling of intimacy and proximity between Martin and her audience. Martin walks to the convenience store and down a suburban street, chatting on the phone. DuVernay is working in the mode of intimacy as identification, of the subjective experience of cinema as a conduit for empathy and understanding.

The problem is, these are not scenes and sequences that stand on their own. In every instance, an insistent, underlining score prods the audience toward the correct reaction, each fateful close-up emphasized by sorrowful strings or sentimental piano. Suspense is drawn out in the condescending melodrama of slow-motion, where the ensuing gunshot seems fated. There has never been a linear relationship between empathy and behavioral change, between emotional attachment and personal application. Film can lapse into manipulation, but that manipulation, when it works organically, feels almost logical rather than coercive. If entertainment is the default association of cinema for most audiences, what is the filmmaker’s responsibility to navigating that association? This is the basis of Austrian director Michael Haneke’s moral aversion to Schindler’s List. “The mere idea of trying to draw and create suspense out of the question whether out of the shower head, gas is going to come or water, to me is unspeakable,” he said. Origin functions at the level of Hollywood didacticism, which means it indulges the same tropes as any Oscar-chasing tearjerker, and cannot be separated from entertainment.

A similar failure in this direction is Raoul Peck’s 2021 HBO miniseries Exterminate All the Brutes, which aimed to braid commentary of colonialism, genocide, and racism with intensely violent reenactments of the historical episodes it follows, from Columbus’s landing on the North American continent to the Trail of Tears. Where Exterminate All the Brutes operated in a shock-and-awe mode, with each supposedly unflinching whipcrack and rape delivered as part of a moralizing polemic in the same vein as 12 Years a Slave, Origin appeals to a more standard liberal crowd who would rather cluck their tongues in dismay and dutifully buy a copy of the book than deeply engage with its implications. Origin is a film for people who love Bill Gates, a film where institutions are seen as altruistic theaters of social change, and where the lessons of history are straightforward and easily ascertained.

The film resorts to rote dramatizations of the Holocaust and Jim Crow racism. It holds up interracial, or intercaste, love as a transgressive, history-changing act. Its versions of journalism and academic research exist only in galas, museums, and lectures that appeal to wealthy change-makers. It mistakes maudlin sentimentality for actual feelings. Most of the intellectual conversations depicted in Origin are montaged without dialogue, without any recourse to believing the audience could be interested in the finer details of Wilkerson’s argument. Instead, re-enactments substitute work. Disparate concepts are collapsed, pieces shoved together without fitting. This has led to a refrain that the film would have been better suited as a documentary, a medium where DuVernay has found success in the past. But, at the conclusion of Origin’s two-and-a-half hours, I was left with the impression that a documentary would have left DuVernay needing to grapple with Wilkerson’s work, to say nothing of Caste’s critics, more than she had any desire to.

Hari Ramesh, reviewing Caste in Dissent Magazine, wrote, “Adopting caste as a transnational historical category generates some important insights, but pressing it too far risks confusing different political circumstances. When we conceptualize and resist racial subjugation first and foremost because it is a caste system, we risk losing vital, context-born insights that might aid and energize our political endeavors.” Origin isn’t interested in context. For a film that aims to fold various sociological histories into a single concept, there’s a shocking, or perhaps unsurprisingly blatant, lack of material discussion. “Capitalism” is mentioned once in passing. Money seems to exist as an ephemeral concept: plane tickets are booked, contracts are negotiated, salaries are paid, but all offscreen. The movie depicts Wilkerson as someone who floats above her theory, unmoored from the same concerns as her subjects.

All of this would be easily dismissed if DuVernay wasn’t going out of her way to impress the importance of Origin onto the world. In an interview with David Remnick at The New Yorker, DuVernay had the following exchange:

I wanted it to be out this year.

Why? Because of the election?

Yes. I wanted it to be out this year. I want us to pay attention. When I say us—this whole country. I really feel like we are tired. We are exhausted, and it is hard to focus because there’s so much going on. We are overstimulated, and we have got to wake up and focus on what is happening. I want this film to contribute to that conversation . . . this transition of power that is to come, perhaps. We have to figure this out.

Here, DuVernay’s film is situated not just as a lightning rod for the nation’s soul-searching, but as an actual means of steering reality. As Lauren Michele Jackson wrote in her review of Caste, “It’s a nice place to be, a place where we can believe people in power are one sincere interaction away from radical empathy.” Of course, a member of the Gates family did help finance Origin, along with the Ford Foundation and the Emerson Collective. Trust in a facile understanding of democracy and civic engagement is what such places aim to generate. Origin seeks to interrogate humanity’s collective understanding of hierarchy and subjugation firmly within the parameters of the C-suite. At a certain point, it becomes unclear what the film actually is. If it's an investigative thriller, what few elements there are cheapen the drama by resorting to ridiculous instances of shorthand. A scene in a German Holocaust museum features close-ups of excerpts and quotes on the walls, snippets without deeper context. Then again, DuVernay puts too much stock in the humanizing power of a close-up.

Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter, she said, “If I’m showing you enslaved people on a ship, I’m going to show you a close-up of the faces. You hear the words [via Isabel’s voiceover narration], ‘This was the son of the baker.’ ‘This was the niece of …’ It’s humanization. The same in the concentration camps. It’s not just a mass of people. Break out and show the one woman who sees her son and says, ‘I’m going to touch you, one more time.’ ” But what the audience is shown aren’t people, but caricatures. Any texture found in the film is in the image, not the material. Fawning celebrations of German memory culture, passing references to the Armenian genocide, Palestine, indigenous communities—these are gestures, not politics.

The end result is a movie that seeks to inspire thoughtfulness without trusting its audience to do any real thinking (prime example: a third-act whiteboard montage where Wilkerson practically speaks in direct address to the viewer about her book’s argument), a movie that hopes to insulate itself from critique because its importance should be plain.

In Origin’s final moments, as Wilkerson narrates her triumphant findings over a tracking shot of her moving through her mother’s home, the historical characters introduced throughout the film—Trayvon Martin, Nazi turncoat August Landmesser and his Jewish lover Irma Eckler, sociologists Elizabeth and Allison Davis, Dalit activist and scholar B.R. Ambedkar—stand outside on the lawn. As Wilkerson passes, each figure nods or smiles at her. It's a stunningly ridiculous sequence, followed by an even more ridiculous series of title cards connecting Caste’s book sales to the results of the 2020 election, but it makes sense in accordance with the film’s sprawling, mawkish construction. Its implication is nearly identical to Our Friend, Martin’s: understanding the past enables you to change the future. But one comes away from Origin as one might a TED Talk, with all the attendant fealty to the ingenuity of donors and foundations clanking in the background. At least with the kid’s cartoon, I sort of believed it.