On Monday, Vanity Fair published the first excerpt of Olivia Nuzzi's monograph to sexting with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a book titled American Canto. The book, as Nuzzi claimed in a glamorized profile published in The New York Times, was written almost entirely on her phone while she was hiking, and this excerpt appears to be robust proof of this claim. Here is Nuzzi's introduction to RFK Jr., a man who, perhaps in some millennial allegiance to J.K. Rowling—another powerful woman under the delusion that she has been cancelled—she refuses to name:

"I would take a bullet for you,” the Politician said. He always said that. “Please don’t say that,” I said. I always said that.

The whole excerpt is pretty much like this: simultaneously clipped and overcooked in a way that suggests Nuzzi has mistaken having heard a lot about Joan Didion for being able to write like her. I posit that using conjugations of "to say" five times in four sentences is not evidence of style. But this repetition is rendered almost immaterial by what follows:

From his mouth the bullet theoretical launched the bullet possible. I did not like to think about it. About the armed man at his speech. Or the armed man who broke into his home. Or the armed men he paid to guard him from armed men who sought to harm him while the federal government denied his pleas for protection from the security agency whose modern protocols were carved by the same bullets that cut boughs from his family tree and cut the track of the American experiment.

There is much to ponder here. Where did the bullet theoretical launch the bullet possible? From his mouth, of course. Does she like to think about it? No! Neither should we, really, spend any more time than we already have on the idea that from his mouth the bullet theoretical launched the bullet possible, as, I am guessing, bullets theoretical are wont to do. If I may, to quote Nuzzi herself, "Please don't say that." After such an arrangement of words, the run-on sentence at the end comes almost as a relief; at least here the bullets are simply bullets.

But just as you find yourself struggling to understand what it means for a bullet of any kind to cut the track (what?) of the American experiment, Nuzzi delivers the goods and invokes what, to me, should be the heart of any confessional about RFK Jr. This is how she summons the worm:

I did not like to think about it just as later I would not like to think about the worm in his brain that other people found so funny.

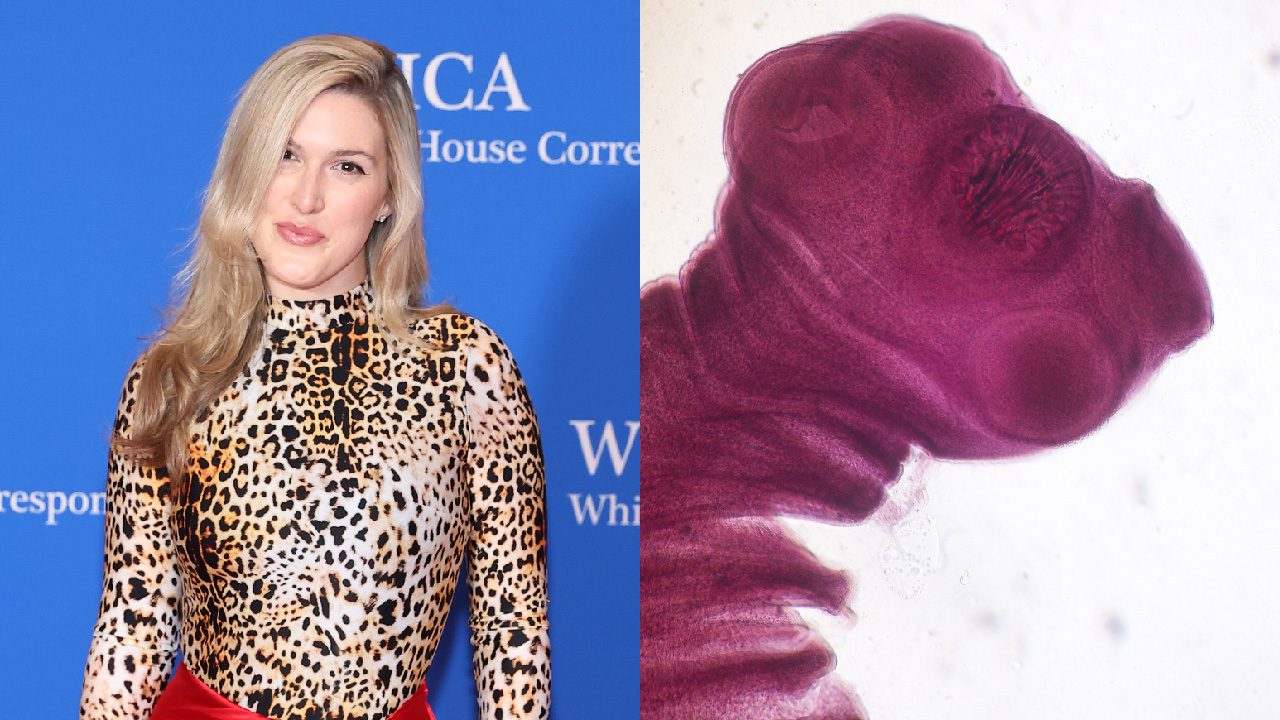

There is no honest way to tell the story of RFK Jr. and his recent, catastrophic rise to power without naming the brains behind the operation, or, rather, who was eating the brains behind the operation. Remember that RFK Jr. learned about the worm from a dark spot that showed up on his brain scans after he'd been experiencing memory loss. Remember that a doctor at NewYork-Presbyterian called him to say that the spot was a dead parasite. Remember that RFK Jr. relayed this information in a deposition where he said the dark spot "was caused by a worm that got into my brain and ate a portion of it and then died," a sentence that might be more beautiful than any found in American Canto.

RFK Jr. did not unveil his worm to the public as a fun fact about him. He only revealed his brainworm in an effort to prove that his worm-related cognitive struggles had diminished his earning power, as he was undergoing divorce proceedings from his second wife, Mary Richardson Kennedy, who would later die by suicide.

It is also true that it is objectively funny to have a worm in one's brain. Yet Nuzzi takes the worm very, very seriously:

I loved his brain. I hated the idea of an intruder therein. Others thought he was a madman; he was not quite mad the way they thought, but I loved the private ways that he was mad. I loved that he was insatiable in all ways, as if he would swallow up the whole world just to know it better if he could. He made me laugh, but I winced when he joked about the worm.

This is perhaps the most revealing section of the excerpt, in that it offers a glimpse into the no-doubt peculiar experience of sexting with RFK Jr. Never mind the sentence "I hated the idea of an intruder therein." Never mind that Nuzzi refuses to name the "private ways he was mad," which apparently stand in contrast to the many public ways he was mad, because here she delivers the goods, sharing what might be the single direct quote from their sexts:

“Baby, don’t worry,” he said. “It’s not a worm.”

Baby, don't worry, it's not a worm. These are the words any political reporter yearns to hear from the man whose brain she has come to love, whose brain has now been revealed to have been predated upon directly by something small and slimy and invertebrate, a creature that could have been controlling the Politician like Remy in Ratatouille, tugging at RFK Jr.'s ears so that the mindless automaton could dismantle the very foundations of public health that have, for so many years, helped us live longer and healthier lives. After all, creating the conditions of mass illness and death could only be the agenda of a parasite.

Nuzzi proceeds with what she presents as foolproof evidence that the worm was, in fact, not a worm at all:

A doctor he trusted had reviewed the scans of his brain obtained by The New York Times, he said, and concluded that the shadowy figure was likely not a parasite at all. He sighed. It was too late to interfere with what had already vaulted from the sphere of meme to the sphere of screwy legend, but at least I did not have to worry about the worm that was not a worm in his brain.

Here's a question: Was this book fact-checked? If it was, I would love to know more about any conversations that might have taken place between a Simon & Schuster fact-checker and whoever RFK Jr.'s "trusted" doctor might be.

In the profile of Nuzzi that ran in The New York Times, she seems thoroughly convinced that her tryst with RFK Jr. ruined her life, a claim that would appear to be immediately contradicted by the profile in which it is found. But of course her life is not destroyed; it appears better than ever. She is the West Coast editor of Vanity Fair, and her book has been attracting a maelstrom of press, including this blog.

In the rest of the American Canto excerpt, Nuzzi threads in statistics about gun violence and the Palisades wildfire that swept through Nuzzi's new home of Los Angeles, killed 12 people, and became one of the most destructive wildfires in the history of the city. Nuzzi ends a paragraph that cites several American gun violence statistics with a metaphor: "I loaded a gun and set it on my nightstand." The gun on the nightstand is, I suppose, sexting with RFK Jr., though I cannot to speak to whether the bullets inside the gun are theoretical or possible. The wildfire gets the same treatment: "You cannot outrun your life on fire," Nuzzi writes, possibly into her phone, at the conclusion of a scene where she watches the wildfire burn from the safety of the Pacific Coast Highway. If you'll allow me to once again return to the words of the poet herself: Please don't say that.

We'll have to wait for American Canto Part 2 to see if Nuzzi can outdo the bamboo metaphor.