PITTSBURGH — I was a little surprised by the seriousness of The Andy Warhol Museum. For an artist I associate with playful experimentation, the seven-story building off the northwest bank of the Allegheny is more a tribute to the professionalism, work ethic, and marketing acumen that made Warhol the most recognizable artist of his era—or any that's come since. The layout is tightly chronological, with the four main floors each representing a decade in its patron saint's career. The information presented is devoid of tabloid gossip, keeping Warhol's international fame completely incidental to the narrative of his artistic output. And the only time I laughed out loud was at these deadpan info boxes next to Oxidation, which never break character even as they describe the process of creation through urination, and note ongoing study of the piss painting with a straight-faced "Conservation Challenge."

It was mostly for this reason that I felt like I had trouble gaining a foothold in whatever the museum was trying to teach me. Through the '50s and '60s floors I gawked at the celebrity faces, absorbed the pop of the colors, and contemplated giant dance steps on the wall. But I didn't feel very much at all. That is, until I made it to the '70s floor and got surprised by Silver Clouds.

Described on the wall as "paintings that could float," Silver Clouds is a three-quarter walled room filled with plastic balloons, with fans on either side. The balloons are in varying states of health—some are kissing the ceiling, some have felt their helium mostly decay, and the best ones are somewhere in between.

Yes, you're encouraged to touch the balloons, and I did. I poked at them, admired my distorted reflection in them, and watched closely as they took unexpected paths around the room. I limboed as they glided over my head, marveled at their midair flips, and played goalie at the entryway when they opted for an unruly turn. I smiled at the simple, innocent fun of it. The burden of trying so hard to love this place was carried aloft.

Later on the floor, however, came the spot that I was already prepared to hate, and it was worse than I thought it would be.

My entry point for Warhol's swingin' '60s "Factory" scene in New York City, beyond a teenage love for The Velvet Underground, was its eagerness to mess around with gender and its inclusion of trans women. The most enduringly famous of them was the gorgeous actress/model Candy Darling, who appears, among other places, in Paul Morrissey's Warhol-produced Women In Revolt like Marilyn Monroe if she only ever got one take with zero prep. She died at 29 years and four months old, which I suddenly realized is younger than I am now.

Candy's not quite the lodestar for me that she is for some other trans girls, but I still feel a protectiveness and a kinship with this woman who suffered through an era when even fringe cis artists struggled to think beyond the gender binary. One of the many reasons I think Fran Lebowitz is a hack and a fraud is some stupid stuff she's said about Candy. When people look at or talk to me a little too inquisitively at parties, I comfort myself with the thought This is what Candy Darling must've felt like. I wanted more of her than just the one photograph I saw at the Warhol, but I did see the museum's special little corner for queers: Ladies And Gentlemen.

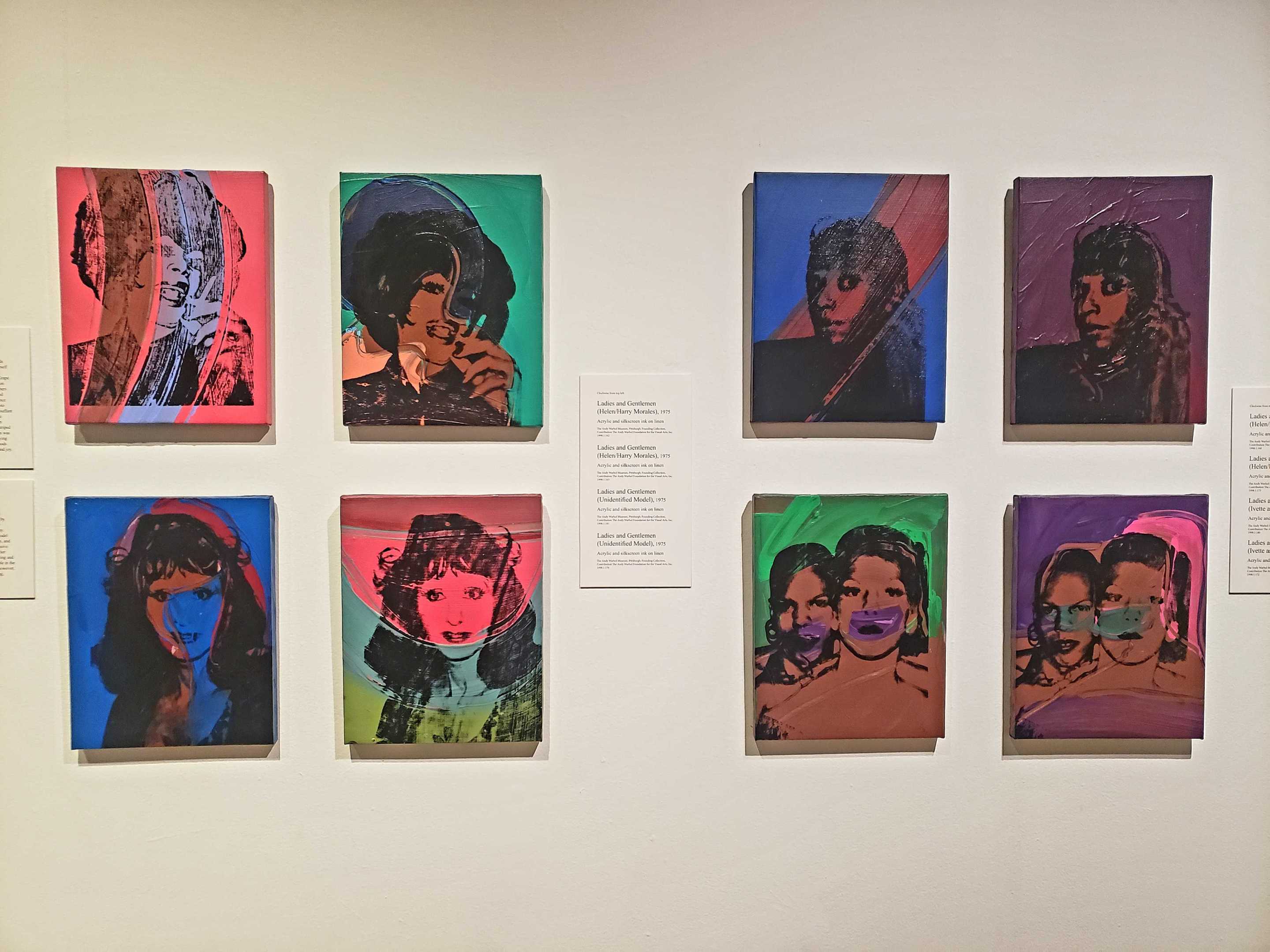

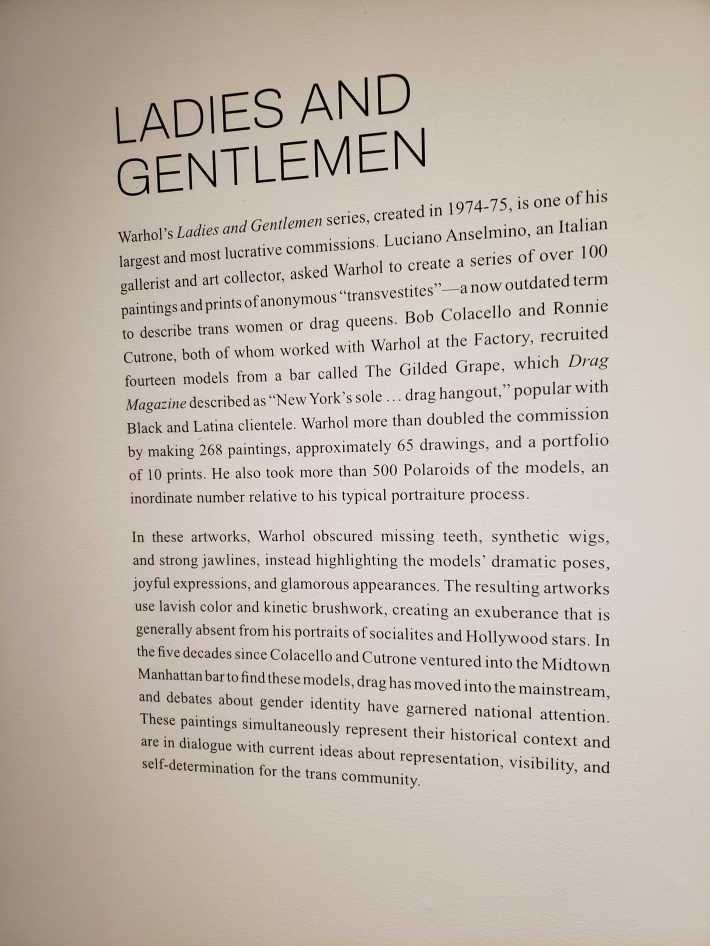

The winkingly titled Warhol series from the mid-'70s saw him apply his much-imitated portrait style to depictions of trans women and drag queens (including Marsha P. Johnson). That in itself is not a bad concept, but the sin of it was that there was no credit for any of his models when they were first exhibited, apparently following his leering patron's command that they be "completely anonymous and impersonal." People who cared more about their identities eventually went back and figured out the names of all but one.

"Andy Warhol silkscreens of Marsha sell for $1400 in a Christopher Street gallery while Marsha walks the sidewalk outside, broke," wrote the Village Voice in 1979.

The anonymizing act of omission frustrated me in much the same way as Lou Reed's "Walk On The Wild Side," the cis male singer's massively successful tribute to the Factory. The first verse is about Holly Woodlawn's transition. The second is about Candy Darling giving blowjobs. The overwhelming impression I get is that Reed really wants you to know he hung around trans women who fucked, like he's using this odyssey through the freaks of gender as a means of beefing up his own cool.

All of this is context ripe for discussion, and I'd happily patronize a museum that was willing to explore it all. But the Warhol, instead, took a cowardly route, opting for vague neutrality in place of insight or empathy. At a time when I'm freaked on a daily basis about whether or not we can safely use our passports, or if our clinics are going to shut down, or what's going to happen to those of us they're throwing in men's prisons, the Warhol merely offers that "debates about gender identity have garnered national attention." Its copy is nonsense that reads as if it were specifically designed to prevent cis people from thinking.

It might actually be the angriest I've ever been in a museum, looking at this and wondering how different the phrasing would be if it were a zoo exhibit teaching humans about a rare species of animal. The presentation of Ladies And Gentlemen solidified my belief that the "exotic" transgressions of gender around the Factory only mattered to the men there insofar as it made them seem rebellious by association. The museum's celebrity portraits of the '70s, like Ryuichi Sakamoto and Douglas Cramer, included sufficient write-ups to prove their notability. But in the telling of the Warhol, it's Bob Colacello, Ronnie Cutrone, and Luciano Anselmino who deserve the credit, rather than the "fourteen models."

I felt pretty off-center when I left this section. I tried to go back to Silver Clouds to recapture a more pleasant emotional state, but the spontaneity felt drained from it all. I wandered through the '80s floor, not engaging closely with the Basquiat collaborations. But then I stumbled into an unoccupied room that helped salvage the trip. Inside were two gigantic Skull paintings, including this one:

The picture doesn't do justice to its size. It reminded me, in its majestic portrayal of death, of the giant Christ on the cross mounted at the front of my Catholic church where I grew up. You could lose yourself in the darkness of the eyeholes alone, and the unnatural choice of color around it only adds to the surreal, macabre wonder of the viewing experience.

The sick morbidity and strange beauty of Skull somehow matched perfectly all that had been storming in my brain over the last several weeks (and several minutes). It's the kind of work that helps me grasp at the idea of something larger than myself—and that this something may not be pure joy but a force with a healthy quotient of madness. The thing about a skull is that it could represent anyone at all: Jackie Kennedy or my neighbor, Elvis Presley or the guy walking past in a Mario Lemieux jersey. And the thing about a skull at this scale is that it can be nobody, just a commonplace necessity for our existence placed in a lofty and unobtainable spot. Maybe there's actually something kind of funny about that.