Natalie Nakase is many things: a 5-foot-2 former walk-on who became the starting point guard for UCLA, a WNBA champion as an assistant coach with the Las Vegas Aces, and “a unifier,” as Golden State Valkyries general manager Ohemaa Nyanin put it in an introductory presser last October. When the Valkyries play their season opener in San Francisco this Friday, Nakase will add to that list, becoming the first head coach of the franchise, and the first Asian-American head coach in WNBA history. She is a third-generation Japanese American from Southern California, raised by a basketball-loving father who kept his daughters in the gym the way some parents bring their children to church.

Basketball has been an integral part of Japanese-American communities on the West Coast since the early 1900s. Shaped by forcible internment during World War II, Japanese-American basketball leagues (colloquially known as the “JA leagues”) flourished for decades as a way to cultivate second- and third-generation talent, and still operate to this day. The use of digital archives dating back to the 1940s, as well as interviews with relatives and members of the JA league community, demonstrates how the story of Natalie Nakase is the story of Japanese-American basketball. Go through her family history, and you’ll find competition and resilience that transcends the sport itself.

To conclude the 1943 basketball season at Rohwer Relocation Center, in the southeastern corner of Arkansas, the boys and girls “inter-Center” all-star games took place on a Sunday afternoon. Rohwer’s all-stars faced off against opponents from nearby Jerome Relocation Center. All the players were incarcerated in prison camps. They competed on an outdoor dirt court, built atop a strip of drained swampland, surrounded by mud, ringed by barbed wire fences and guarded by military police.

Until recently, the young basketball players of Rohwer had never stepped foot in Arkansas. They were almost all from California, growing up amidst the brown plains of Lodi or the city blocks in downtown Los Angeles. West Coast kids and Nisei (second generation) took to the sport in an era marked by discrimination, when many Japanese Americans were systematically banned from buying or owning property, not to mention exclusion from organized athletics. Perhaps, the thinking went, by mastering a homegrown sport, the Nisei would be more warmly received by their fellow Americans.

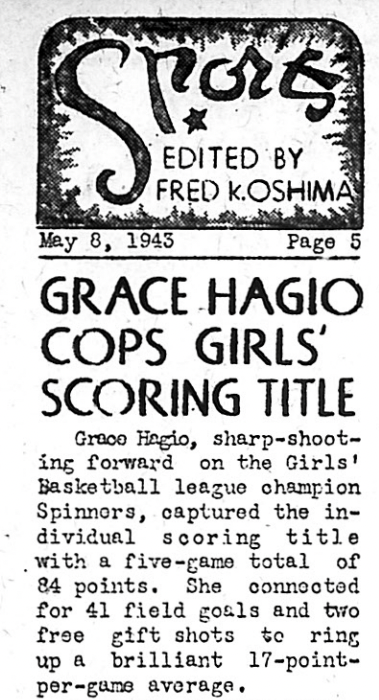

At the start of the 1940s, many Nisei were building flourishing basketball careers. Rohwer’s Tosh Ihara was a standout freshman on UCLA’s 18-6 “lightweight” team during the 1940-41 school year, while Grace Hagio led the Stockton Busy Bees to defeat all Northern California rivals in the Young Women's Buddhist Association, outscoring opponents 477-228, according to archival records. Hagio, known by her nickname “Yoshi” in her hometown, was a dominant offensive presence as a forward on the Busy Bees, while the team competed across the western U.S.

But no amount of skill on the court could counter the wave of anti-Japanese hysteria that overtook the country during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became increasingly preoccupied by the perception of Japanese Americans as a potential military threat—despite intelligence from reports, ordered by Roosevelt himself, finding no serious threat to the country. Following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, Roosevelt invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, widely credited as paving the way for the impending incarceration of Japanese Americans. (The beats of this process may sound familiar to those paying attention to the current presidential administration.) Despite opposition from numerous high-ranking government officials, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February of 1942. What followed was the forced removal of over 120,000 people of Japanese descent on the West Coast, including American citizens and young Nisei hoopers from Washington, Oregon, and California, detained and sent to prison camps in remote areas of the country.

Athletics, including the increasingly popular sport of basketball, were an essential outlet for Japanese Americans who endured incarceration, as documented by the local newspapers published in each camp. Using digital archives provided by the nonprofit organization Densho, I found clippings and articles full of details about the Nisei athletes’ dedication to the sport. At Poston Relocation Center in Arizona, residents evaded the burning 100-degree weather by hooping at night, cutting down cottonwood trees as poles for floodlights. All-star “quintets” received special permission to travel beyond camp for showdowns against local high schools; at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, the all-star boys basketball team practiced outdoors in freezing weather before traveling to a nearby Mormon town to take on future regional champions Lovell Westward High School. And at Rohwer, where the 1942-43 basketball season was troubled by terrible weather and a contaminated water supply that had to be boiled before drinking, the all-stars defeated their rivals from Jerome. As Bradford Pearson wrote in The Eagles of Heart Mountain, which tells the story of that camp's undefeated high school football team, some of the camps were built on former swampland so easily overrun by floods and poisonous snakes that landowners had abandoned it long ago. The land wasn’t much better for basketball courts.

Around the same time as that Rohwer all-star game, a young woman named Takayo Maeda arrived at the Arkansas camp. Months earlier, she’d been separated from her husband Kenichi and infant son, held back at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in California to give birth alone to her second-born son. According to her eldest son's account, published in 2022, she and other internees were forced to live in converted horse stables. Finally, Takayo was sent by the War Relocation Authority via train, unaware that she was headed to be with the rest of her family in the prison camp. With her was her baby, Shigeo “Gary” Nakase.

Decades later, on the way to a basketball tournament in Tennessee with his daughter, Gary Nakase drove through the site of what had been Rohwer Relocation Center. According to Natalie, he didn’t talk much about his family’s experience at the camp, or of the fact that he was born into incarceration at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in October of 1942. “He doesn’t speak about it unless we ask,” Natalie said in a 2019 interview. “From the small pieces that my dad did tell us, my grandfather had everything taken away from him and had to start over from scratch.”

Kenichi Nakase and Takayo Maeda's return to California in 1945 was difficult; they struggled to rebuild amidst anti-Japanese sentiment whipped up from the war, and moved between farm towns as both parents worked the fields. According to Gary’s brother, Frank Nakase, the family settled in 1954 in the suburban city of Whittier, near Los Angeles. The family swelled to the size of a small hoop squad itself, with five more children born after Gary for a total of seven.

“I think my dad always tried to protect us [from] the struggles that he went through,” Natalie told me. “I think that's why my dad never brought that up, and then if pain ever came to us, he was like, ‘No, don't pay attention to it.’ My dad was iconic, man.”

In that same post-war period, the JA leagues expanded. New leagues with roots in the camps formed across the West Coast, largely revolving around Buddhist centers and churches, with raucous showdowns between rival cities, from Seattle to San Jose to Los Angeles.

At a time when girls basketball, if offered in schools or physical education programs at all, was subject to highly restrictive rules, the JA leagues actually welcomed women to the court. For her book When Women Rule the Court: Gender, Race, and Japanese American Basketball, Dr. Nicole Willms interviewed Ed Takahashi, a local businessman from Los Angeles who was in charge of the youth leagues for the Japanese Athletic Union in the late 1960s. “What I did was, I changed the rules,” Takahashi told Willms. “Instead of… where you had three girls on defense and three girls on offense and they could never cross the line, and you had two dribbles and you had to pass, I changed it to boys’ rules.” According to Willms’s analysis, gender exclusion and gendered hierarchy in the JA leagues were often “subdued in favor of asserting a Japanese-American identity.” This meant a more promising environment for the women’s game, particularly in Southern California.

“I stuck with the Asian leagues,” recalled Colleen Matsuhara, who played at Sacramento State and was an assistant coach for the Los Angeles Sparks in 1998-99. As a teenager, Matsuhara quit her high school team for better opportunities in the JA leagues, where she competed with a sense of survival. “Very deep in the subconscious, at least for me,” Matsuhara told me, “is that I was outraged when my parents told me about camp. Like, they [had] to come back and start from the ground up. You can’t take anything for granted.”

As the Nakase family entered the 1960s, their Nisei kids developed a passion for basketball, primarily led by Gary, a hyperactive teen who constantly wanted to play. “He was the one who wanted to get a basketball hoop and put it up on the garage,” said Frank Nakase, who admired his older brother’s basketball talent. “I recall him being able to touch the rim with his hands with a running start. He was very quick and very fast, and really a crafty player.”

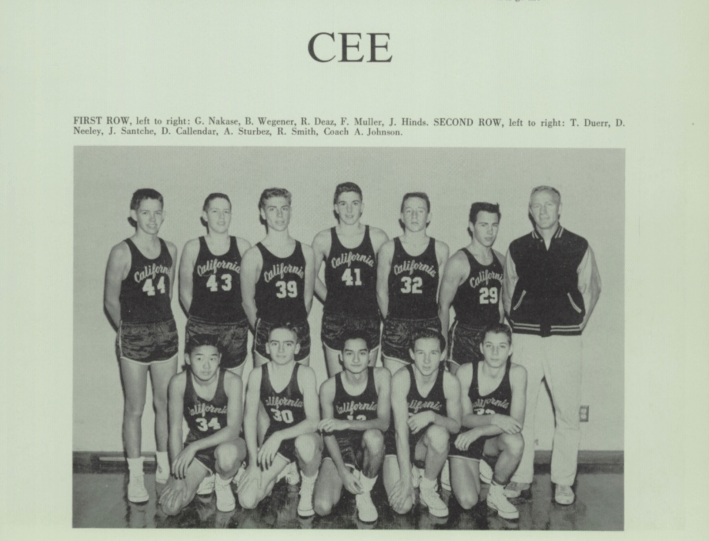

As a senior at California High School in Whittier, Gary is pictured on the boys basketball “Cee” team in 1960, one of the few Asian-American players to compete at his school. “At that time, being a Japanese person and a minority, you’re easily overlooked,” Frank Nakase told me. “I’m sure he could have played varsity, but because of his size he was overlooked.”

By the time the JA leagues reached their prime in the 1970s—with a reported 162 Japanese-American teams in the Bay Area alone for the 1973-74 season—Gary was deeply involved in Orange County’s local recreational leagues. After graduating from California Polytechnic State University with a horticulture degree and meeting his wife Debra in a coed volleyball league, Gary ran a successful landscaping business, spending much of his free time playing and promoting recreational sports.

Later in life, Natalie learned from one of Gary's relatives that her father got his renowned work ethic from Kenichi. "When I went to Japan, I was able to meet one of my dad's second or third cousins," she said. "He only spoke Japanese with very little English, but what I got from him was that my grandfather was the hardest worker he's ever known. I'm like, 'OK, no wonder that my dad is who he is. No wonder I am who I am.' Because it's come through our bloodline."

The community around Gary also benefited from his dedication. “The father of adult sports, Japanese-American sports here in Orange County,” said Jesse James, who met Nakase as a friend and mentor in the mid-1970s. The two men, along with Gil Takenaga, were both tight-knit and fiercely competitive with one another. And in a meeting in 1981, according to James, the men created the Orange Coast Sports Association, an organization that still exists to this day.

Around that same time, Gary hoped to have a son, so he could coach him from a young age. "I was supposed to be Nathan," Natalie told the San Francisco Chronicle. Then he had a third daughter.

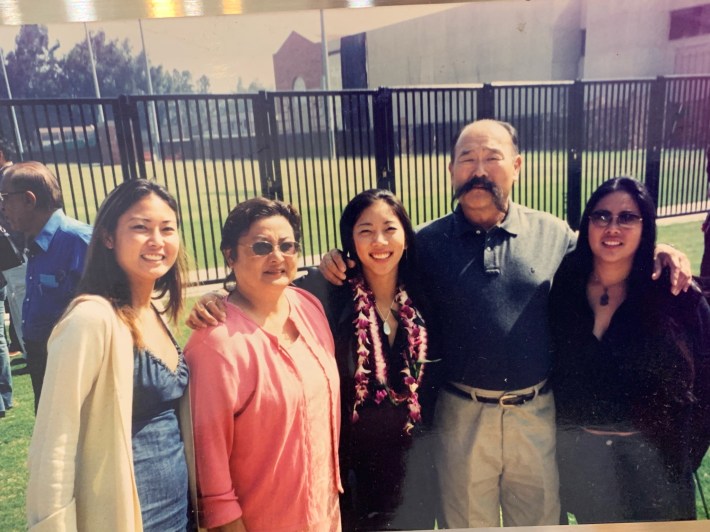

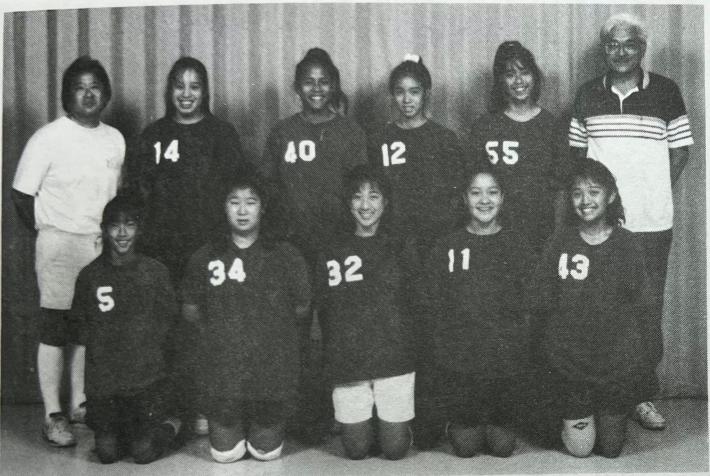

Nicola, Norie, and Natalie Nakase grew up in basketball gyms, watching their father play in the JA leagues. Gary’s close-knit group of friends continued their love of basketball; now with their own kids, the competition changed. “They didn't really care about how much money they made,” Nicola, the oldest of the three, told me, remembering the intensity of the youth leagues. “But they did compare us based on how well their kids did in sports.”

Their obsession was distinctly Japanese. “Traditionally, like Asian culture, you would think you should be studying, becoming a doctor, becoming a lawyer, right?” Nicola said. “But not the Japanese Americans, two generations in. No, you're gonna play basketball.”

As Gary’s youngest, Natalie was different from her sisters. “More so than athletic,” James said. At three years old, he said, she was “swimming underwater like a darn fish.” Natalie was a lot like her father: unable to sit still, and a sponge for his love of basketball. “We had tons of VHS tapes of games, you know, instructional tapes from old college coaches that he recorded,” Nicola remembered. “[Our dad] was obsessed with learning different techniques and different things, and then making us do it.” And Natalie, far more than her two sisters, loved it.

“All I knew was playing basketball every single day because he played,” Natalie told reporters in her Valkyries introduction. “He made us play every single day. That’s all we knew. Because he was passionate about the sport, I became passionate about the sport.” Gary’s youngest daughter trained with him every Sunday.

“When most people say ‘I'm going to church,’ I was like, ‘Oh, I'm going to basketball practice,’” Natalie told Willms in 2008. “Everyone always said, ‘Do you go to church?’ And I was like, ‘Well, I go to basketball church, is that considered the same thing?’ I just called it that because it was every Sunday morning.”

Gary fully invested in Natalie’s basketball career. He started Natalie in the JA leagues early, always having her play with kids a couple grades ahead of her. While he found success with his nursery business, using skills passed down from his own parents’ agricultural expertise, Gary hired various coaches for his daughters: strength and conditioning, dribbling, and shooting, repeated compulsively with the goal of mastering the game.

Through middle school, while Natalie was often the tiniest player, she also became the most “relentless and fearless” on the court, according to her oldest sister. “Other teams’ parents would cheer for her, which was really funny because she would be like the smallest person on the court, but she would just be very feisty,” Nicola said, remembering Natalie’s time in AAU. “They just liked the way she played, so they would be cheering for her too … she would get a lot of fans just because she was so energetic.”

As a point guard at Marina High School in Huntington Beach, Natalie Nakase led the team to its first CIF-SS title in 1998, earning Orange County Player of the Year. She drew some attention from recruiters—including Colleen Matsuhara while she was the head coach at UC Irvine—but Natalie had become dead set on playing at UCLA. At her height, she faced an uphill battle. “She was too short, and she was Japanese,” James said. “So she had two things against her.” Nonetheless, Natalie held firmly to her self-belief, cultivated by her father Gary.

Natalie began her career at UCLA in 1998 by walking on to the women’s basketball team, then redshirted her freshman season after tearing her ACL in a summer league game. By her senior year, she became the starting point guard and team captain. With a player bio describing her at the time as “a coach on the floor,” she became a source of pride among Asian-American communities in Southern California (even if she was often mistaken for a gymnast or tennis player on campus). After a brief professional stint, Natalie began her coaching career overseas, rising through the ranks of the Los Angeles Clippers to become a player development/assistant coach, before she joined the Las Vegas Aces for back-to-back championships in 2022 and 2023.

The throughline of Natalie’s success was her father’s lessons. “My philosophy is going to be tough love, same as how my dad raised me,” Natalie told reporters after the Valkyries’ preseason victory over the Phoenix Mercury. “Strict. Stern. Truth teller.” Like many other Japanese-American families, the Nakases passed basketball down as resilience. With the history of incarceration, discrimination and hysteria not as distant as we’d like to think, generations of Nisei and Sansei (third generation) athletes made Japanese-American basketball leagues a focal point of their communities. This is the culture that shaped Natalie Nakase, whose new challenge is to lead the WNBA’s latest expansion team, with minimal roster depth and everything to prove. Once again, the only option is to start over.

She'll have to do so without her father Gary, who died in 2021. “For those that just don’t know my background: My dad, who also was my best friend, he passed away a couple years ago,” Natalie said in her introductory Valkyries presser. “And so he was always my first phone call. Whether it was life or basketball, that was my first phone call.”

Her voice trembled slightly as she continued, speaking to her obsession with winning. “What drives me is, again, like my dad taught me when I was young: ‘You always gotta be the best.’ And so I almost feel like he has trained me in a way, or he’s raised me, to be where I am today.”