The following is excerpted from a chapter of The Dad Rock That Made Me a Woman, by Niko Stratis. The book is available for purchase now.

The first time I ever remember hearing the Wallflowers, I was covered in blood, moldy produce, and garbage. When the garbage compactor jammed at Food Fair, often the only way to get it running again was to climb through the steel hallway that bridged the hollow expanse of the loading bay to the side of the garbage bin, jump into the compactor, and dislodge the bits of rotten food, expired meat, and old cardboard by hand until the compactor moved again. Once you were sure it was moving freely, you could climb back out through the steel tunnel, which was also often covered in blood and rotten food bits and liquids of unknown origin. I learned quickly to bring a change of clothes, and I never really thought about how crushing it was to be getting paid minimum wage to do this.

My dad never wanted me to follow him into working as a glazier. It’s not that he was ashamed of his work; my dad has always been good at his job and proud of it, and rightly so. It’s that he knew it was hard and dangerous work, and I think if you spend your life doing hard, dangerous work it can wear you down. It’s not that he didn’t want me to work like him; it’s that he was worried about me being weighed down by the spiritual cost of hard and demanding labor. This is a common dad denominator, especially dads who work in labor, that they want something different, something that feels better, for their kids.

I never really wanted to be my dad, but I have always wanted my dad to be proud of me. I still, at the time of writing, want my dad to be proud of me. For all the days he and I share on this earth, I will want this. Not desperate for approval but desiring it all the same. I want him to feel like he did something right in raising me, teaching me, guiding me, and showing me the way. My dad is a very accomplished man in a thousand ways, and I want him to feel like I am counted in that number. Raising me was just as much work as any labor he performed with his hands.

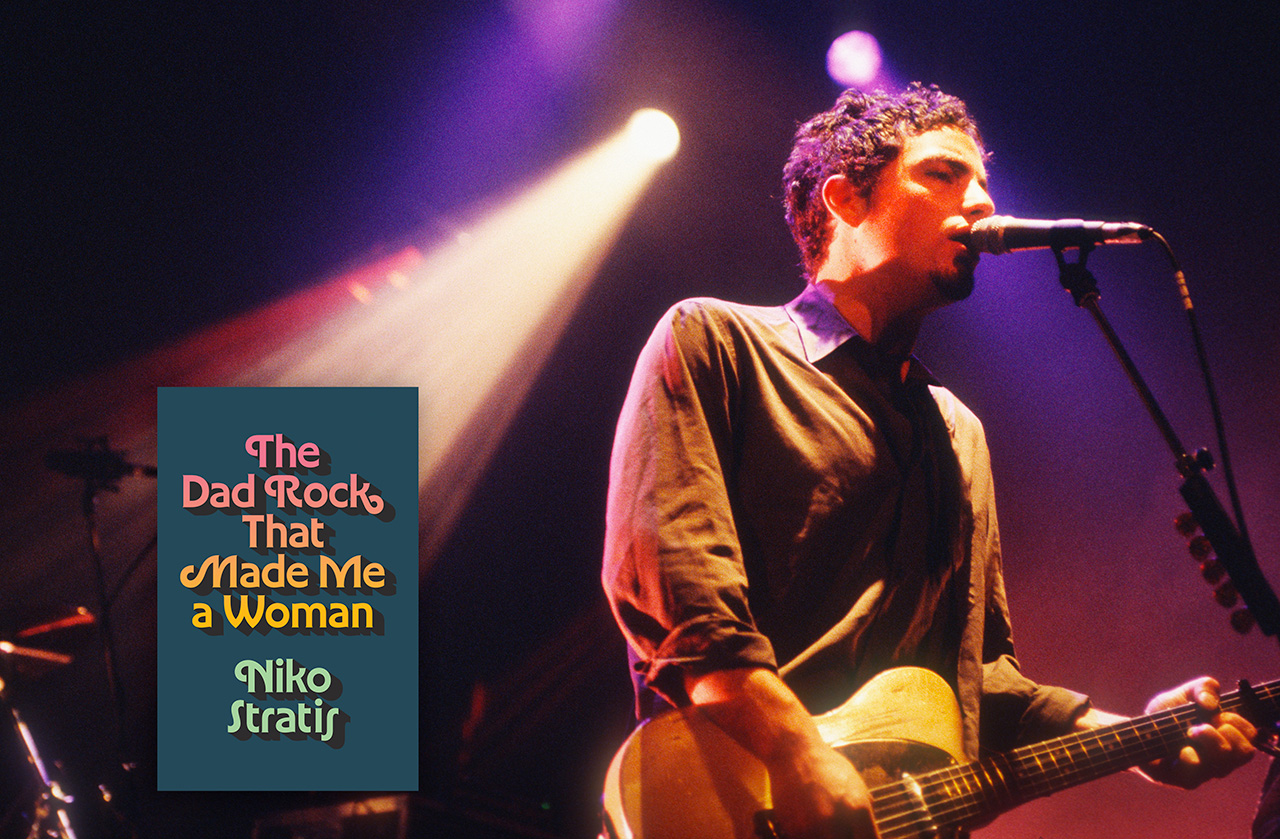

The Wallflowers are fronted by Jakob Dylan, and you will be told immediately that Jakob is Bob Dylan’s kid. I imagine being a musician named Jakob Dylan is like being in Duckburg with the last name McDuck. You can hide the facts all you want, but people are putting the clues together without you. You can hear it in his voice, the tones of his father, the Dylan-esque gravel that inspires his tongue. The influence of his dad shaping the way he finds a way through this life.

I never really understood my dad when I was young—I never understood men in general—but I looked at him as the key detail with which to understand the larger tapestry, a reference piece I could use as a guide. If I could make him proud, then men might see me as something equal. When I was a teenager working a nothing job at a nowhere grocery store, I saw in him this hardworking tradesman, up before dawn, home late, tired and worn through. I started to wonder how I could find a way to emulate him without ever having to follow him into the trade I was being kept at bay from. I looked around the grocery store for the first stepping stone, thought the bakery would be a place to start. Somewhere I could learn a trade that uses my hands, that I could throw myself into, that I could get lost in.

I wanted to make my way in this world on a path I could determine, not ask my dad for help or to open doors for me. I never once thought to sit down with him, ask questions to get his thoughts or his feelings on anything. I made assumptions and drew my life around them.

At sixteen, I asked to be transferred into the bakery at Food Fair. I was going to be a baker. I was going to make my own destiny.

The first single from Bringing Down the Horse, the Wallflowers’ T Bone Burnett–produced second record, isn’t “One Headlight,” which is always a surprising fact to remember. It was “6th Avenue Heartache,” a title winking at Bruce Springsteen’s “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.” For all the Dylan of Jakob’s lineage, you can hear Springsteen in a lot of his work, hear him looking for guidance from the men who came before him as he worked to carve a path to claim as his own. Singles and hits get lost as time washes over our memories, and it’s easy to forget that “6th Avenue Heartache” was everywhere, drive-time radio DJs cutting in with their insistent reminder that this single was from, you’ll never guess, Bob Dylan’s kid.

I believed that all dads were like mine. Protective, caring. Watchful. That all dads hold this one instinct, shared among their kind. Look out and guide where needed, be gentle. But all fathers are not dads, and this is a hard lesson to learn.

The bakery department at Food Fair in Whitehorse in the ’90s was notorious for exactly one reason, which explained why young women didn’t work there: The head baker was a lecherous man who could not let a woman exist on this earth without commenting on his perception of her body, all the things he felt women and their bodies owed him. The things he wanted to do. Women were objects for him to desire and lust after. But it was just talk, always talk. Never serious. And I was by all perceptions a boy, and I believed this made me safe.

I wanted to work in the bakery because I thought this shift in responsibilities would change something in me. This was where I would start finding my own path, discover some passion for dough and kneading that I had never known was there. It took me off the floor and gave me a taste of real responsibilities, no longer part of the common rabble stocking shelves and getting carts. I had transcended and moved into a new arena. Maybe this was how I would make my dad proud, make my own way, and leave my mark.

“One Headlight” is a song that burns slow, like a match struck without need for a flame. The iconic movements that lead us into the music, sparse notes of a guitar, drums without cymbals, the hint of an organ. It’s a perfect grocery store song in that it feels alive, and it feels real and tangible and human. It’s easy to poke fun at or mock grocery store radio rock, but to me and my heart it always feels like home. Songs live and breathe in stores like this, contain all the breadth of their emotions played through shitty speakers hidden away in the ceiling. The music that moves around bodies as they search for something, lost in thought, walking through the world. Lives move through these spaces and are marked forever by them in unseen ways. Dust that builds on the soul to mark time. These are real and human songs that play for everyone, live in all of us, and leave us with their memories. There is, perhaps, no more alive a locale than a grocery store. A beating heart that will always be overlooked and forgotten but will form foundational memories of sound and the banal tactile sensations of the world. Feeling freshly bagged bread in your hands, the brisk chill of water as sprinklers turn on to lightly crest hills of fresh produce. The sound of squeaky wheels on freshly waxed floors, a door opening automatically via a sensor hidden above your head.

This is where I first fell in love with the way that music and the sound of the world can haunt you forever.

All fathers are not dads, and this is a hard lesson to learn.

My first memory of hearing “One Headlight” was after crawling out of the trash compactor chute, covered in blood and expired food and garbage. Standing in a loading bay with a coworker who came along to observe for safety, lest I be crushed by the moving steel wall when it got unstuck. Another guy I worked with who had lent me two dollars the week before to buy a cheese bun and a coke for lunch came barreling in to demand that I pay him back what was owed to him. I stood there like a garbage bag that had come alive, incredulous to the immediacy of his needs and trying to just hear the song playing through the speakers. It was always a welcome change when a new song became a hit and started to enter the drive-time playlists and mix things up. New sounds to break through the old. Listening for Jakob Dylan’s voice as he sang “come on try a little, nothing is forever, there’s got to be something better than in the middle” until there were hands on my shirt shaking me, yelling over the music into my ears.

“Pay me my fucking money.”

I am marked forever by this moment just as I am by the song. This guy whose name I’ve long forgotten yelling at me like a loan shark out for blood over a two-dollar debt still in its earliest stages of delinquency. Shaking the blood and expired food juice loose from my shirt. I didn’t have his money, but it didn’t seem to matter. He was shaking me and yelling at me, and all I wanted to do was listen to the song. Just let me disappear into it for a moment and then I’ll find your money. Shaking me again and yelling, “Just pay me my fucking money; you can afford it now that you moved up to your fancy little bakery.”

This was me learning I had been othered in my shifting career. That moving off the floor and into a department had changed me in the eyes of my once fellow stock boys. Even though I had been here longer than most of them now, even though it was my time to move up, to find my calling. I was still poor, still a worker, still laboring for minimum wage. I was covered in garbage and blood from the garbage bin—couldn’t they see I was just like them? Was I even like them at all? I was suddenly alone, not connected to my former brethren stocking shelves and left alone in a bakery with a leering predator.

I remember asking my older sister what she wanted for Christmas, and she told me she “kind of liked that Wallflowers record,” elevating the band to some cooler level than they had previously held in my heart.

My sister is two years older than me, and in our younger years was the picture of everything I wanted to be. Smart, clever, popular but never untouchably so. She was then and remains today a kind and thoughtful person, not one to be cruel or mean-spirited. She is, above all, a protective and careful person. I know it must have been a burden to have a younger sibling who was the polar opposite of her, quiet and weird, the target of ridicule and implied cruelties. I always wanted to be her, or at the very least get somewhere close to knowing how it must have felt to climb to the top of a social ladder.

Working in the bakery meant that I was often alone, pushing loaves through the bread slicing machine or slathering nearly expired loaves of French bread with garlic butter out of a big tub we kept under the counter to turn them into garlic bread. Grocery store bakeries are exercises in repetition: bring frozen dough out from the freezer in the back of the store; pull frozen sticks of future bread out from boxes and put them into the proofer. Once risen, loaves go into the ovens or get formed into cheese buns.

My lasting legacy was making the cheesiest possible buns. Where my boss would sprinkle cheese on top and call it good, I journeyed the extra mile: rolled the dough in cheese, opened up the pores of the dough and found places to hide flavor. My opportunity to rebuild my connection to the workers in all the other parts of the store was in being known as the person making an art of cheese buns. I was frequently reprimanded for my commitment to the fromage experience, but I could not be deterred. I worked alone, a student trying to become a master, rolling frozen premade dough into cheese-based treasures to curry favor with the people I had left behind.

“One Headlight” is that perfect kind of radio song: a hit that plays endlessly throughout the days that contains notes for everyone to take away from it. The work would often feel soul crushing, banal, and demeaning. But if the right song came on at the right time, your day was saved, even just for four minutes.

I would stand behind the counter pushing bread into the slicer and sing along to the songs that tethered us all together loud enough so that my voice might rise over the half wall dividing the bakery from the checkout aisles on the other side in search of friendship. Singing over to comrades to signal that I was still here with them.

Come on try a little, nothing is forever.

Weekends at the bakery started in the early morning, beginning my lifelong love affair with waking up at 6:00 a.m. to go to work. I think about the stereotype of the hockey dad, their lives told in heartwarming commercials, waking up early and bleary-eyed to make coffee with disheveled hair and plaid pajama pants before driving their future superstars to a rink. Legends chasing assured destiny. My dad lived a different path, was always awake and ready to drive me to work in the ungodly hours of the day because he was always doing the same himself. On weekends he drove me to the Tim Hortons down the street from Food Fair. I had to grab three racks of donuts and drive them over to our own store, where we put them on the shelves in the bakery and sold them for thirteen cents more than the Tim Hortons sticker price.

I got along well with my boss, the head baker, because for a while he saw me as something I was not: the peacock version of myself as I strutted around in front of other men to try and show them I might be counted in their number. A survival tactic. But when he made comments about women to me, I could never follow his logic or play his game, and eventually he came to realize I wasn’t like him. One morning while proofing bread before the store opened, he asked me if I was some kind of fag. A word spit with malice and bitterness. I protested half-heartedly. I liked women after all, but I also understood myself as a body constrained by a gender I did not connect with. He laughed and pointed out my flaws and failures. There was no way a little thing like me could ever satisfy a woman. I was close to being one myself, he said. Weak and timid and easily broken. Then his wife called to chat and he belittled her in cowardly little ways, and I finally saw him as a sad and broken machine playing at some former glory he only ever imagined was real.

He loved the worst music, like KISS, which is always and eternally now a red flag. I would disassociate and let him talk at me about KISS and Gene Simmons, just waiting for “One Headlight” to come on the in‑store radio.

“One Headlight” sounds like a conversation with death, as Jakob Dylan laments the loss of an old friend in the opening verse. In interviews since, he has talked about how he likes to lean on metaphors and images in his work to circumvent directly telling you what he means, but it never stops the song from being read as something much more literal. Jakob Dylan is a songwriter like his father in some ways—despite neither of the two ever speaking much about the other— playfully hiding behind poetic subterfuge to avoid a direct path through. Letting you lose yourself in the rhythms of their work instead.

All the same, the song sounds dark. Brooding and introspective but not cold or detached. There’s something hopeful in here, yearning and sifting back through the past while building the truth of the present. “There’s got to be something better than in the middle.” It felt dark and foreboding but promising, like a transitional season slowly brushing away memories of old weather.

Fall mornings in the Yukon were quiet and crisp. There is a delicate silence to the changing season, a movement that happens swiftly. You only have to blink to miss it.

One fall morning—quiet and crisp—I arrived at work, dropped the Tim Hortons donuts on the counter to be rebranded as our own, and went to the freezer in the back to load carts full of frozen dough to fill the day’s labors. Down the plywood and cardboard–lined hallway of the stockroom, I heard the head baker calling my name, yelling at and about me. The iron-tinged blood of aggression stained his voice. I walked out of the freezer to find his voice and asked what he wanted, and he yelled at me that he had been looking for me all over. When I asked him what for, he looked at me plainly, dead-eyed, and said that he was going to pin me against the wall and fuck me in the ass.

A silence. Nothing. I was a teenager becoming an adult in the void left between his comment and any further movement. I had become just another something to him, an object to leer and joke at. I said I wasn’t feeling well, told him that I needed to go home, that I thought I had the flu, and then I sat outside and cried until I was nothing, walked home alone with puffy red eyes, climbed into bed, and felt numb for a very long time.

I wasn’t seen as a man, I was seen as something else. Something to be preyed on, a victim in the making.

The one part of “One Headlight” Jakob Dylan has emerged to explain is the central theme, one that starts to appear in the first verse. It is about the death of ideas, that there should be a code of respect and appreciation. He was talking about the music industry at large, but the same can be extracted and placed over the lives of so many of us. I assumed that I had safety working in the bakery with this man because he was older, he was a father, he saw me as a body that wasn’t his to turn into an object. But that idea was killed, broken in a moment with an offhand joke in the back hallway of a grocery store. It broke me, killed my spirit and reminded me that I existed as something else.

I had been struggling with the perception of my gender for years. Early memories of stomping around our house wearing my mom’s boots and announcing the desire to be a woman out loud to anyone who could hear emerged from the mental filing cabinets where I had hidden them away. I thought if I worked with all these men in all the man areas of the grocery store that I would eventually learn how to be one too. Like when your classmate spends the summer in Australia and comes back with a somewhat convincing accent. But now it had been made clear to me that I wasn’t seen as a man, I was seen as something else. Something to be preyed on, a victim in the making.

The numbness I felt became a lasting impression. I went back to work a few days later but was a little quieter, more reserved, insular. When songs came on the radio that I liked, that connected me to the world I lived in and the people working there with me, they didn’t hit the same anymore. I sang along less, pretended to be someone else more. This is how nihilists are born, by giving them everything and showing them all the ways in which it will hurt and never explaining how to live with the pain.

I asked to be taken out of the bakery shortly after. Just put me anywhere, I didn’t care. I wasn’t trying to make anyone proud anymore, wasn’t trying to prove to my dad or any other man that I could be someone if they just gave me a chance. I went inside myself and threw away all my ambitions, looked for a way to survive. Leaned into feeling nothing and accepting fate.

“One Headlight” is somber and brooding but ultimately grasping at hope. There is always a way to get by. That one headlight is often all you need to survive—nothing is forever—you only need to learn how to survive long enough that someone somewhere might heal you.

Published with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2025