Of all the ways to learn about the creep of age, the most insidious is to notice that the people who would politely argue with you when you complain about getting old are turning all dead. The second-subtlest is to learn that the people you used to talk about to the people you used to politely argue with about your age are turning all dead too.

Thus, the deaths of Vida Blue over the weekend and Joe Kapp Monday night reminded "those of a certain age," as the Brits like to describe advancing decrepitude, that old is everywhere no matter the vehemence of the denial.

Not that those who deny the inevitable (and yes, we're talking about all of you) need a lecture on the bastard that is the time-space continuum, but Blue and Kapp cast long shadows half a century ago, and it is hardly their fault that 50 years ago turns into a million years ago with unreckoned speed. Most of you vaguely remember neither, and that's the job of being young—rejecting that which happened before you started paying attention under the idiot banner "Best thing/person/event I've ever seen," like your memory is some useful and agreed-upon standard of measurement. Trust us, the only thing that sentence is is an admission that you don't know want to know anything you don't already believe. Your children will hate you because of this, and deservedly so.

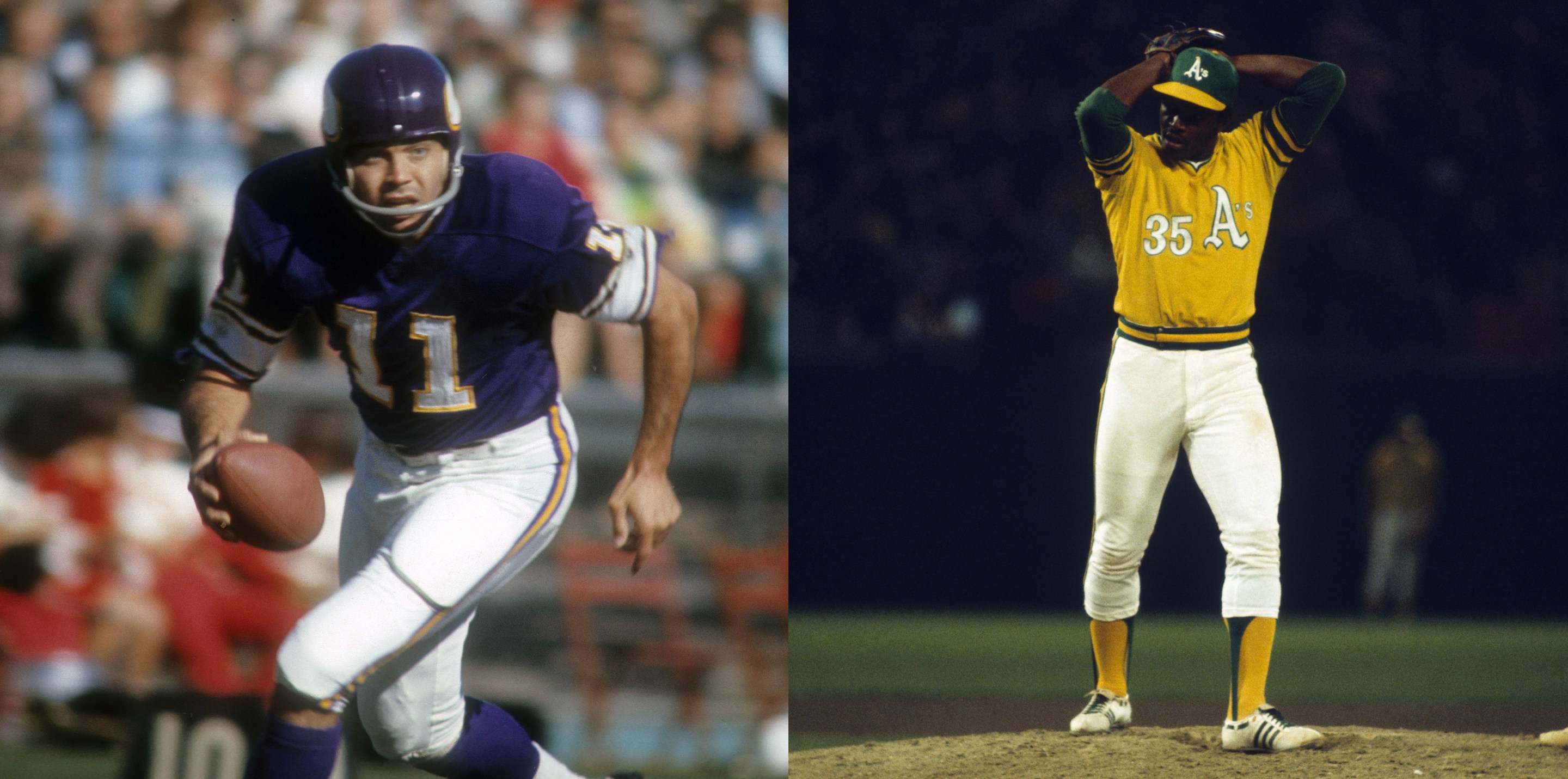

But Vida Blue was a national phenomenon as a 21-year-old pitcher for the Oakland Athletics in 1971, the Tim Lincecum of the age. He went 24-8 with 24 complete games, eight shutouts, and 301 strikeouts when wins, complete games, and shutouts were measurements of pitching excellence, and helped midwife the A's’ early-'70s dynasty with a distinctively explosive pitching motion and a joy for the job that the first miserable Oakland owner, Charlie Finley, needed three seasons to extinguish. Blue later went across the bay to San Francisco and while his performances never matched his early Oakland years, he became one of the few things that A's and Giants fans could agree upon: the pleasure he provided baseball fans when baseball was good at that and the pleasure with which he did the job.

Joe Kapp, on the other hand, was an advertisement for joy through stereotypical tough-guy stuff. He was the last quarterback to ever take California to the Rose Bowl 65 years ago, wasn't good enough to jump immediately into the NFL so he went and won Grey Cups in Vancouver, then came back to the NFL in 1967 and to the perfect place for his stereotype: Minnesota. And not just Minnesota, but Bud Grant's Minnesota, with the winters and the outdoor stadium and the two-bat helmets and the arse-deep-in-snow games. His career there was brief, but nothing warms the heart of the Minnesota fan quite like a quarterback whose breath steam obscures his face, and nothing warmed Kapp for Vikings fans like their 1969 season, the first Super Bowl appearance before Vikings and Super Bowls became synonymous with shoveling your driveway with a popsicle stick.

But even for all that, Kapp's real moment was the day in 1982 when, as the head coach at his alma mater, he created the play that became The Play, the five-lateral kick return in the Big Game against Stanford that ended with Kevin Moen running the ball through the Stanford band. It was for years considered without question the greatest moment in 20th-century college football (we are willing to accept the 2013 Iron Bowl as the game of the current century because worshiping the past leads to sclerosis, and age happens to other people). Kapp had designed (or updated) the lateral concept and, as was his wont, he gave it an elegant nickname so evocative of higher education: Grabass. Grabass worked, a bad Cal team knocked a mediocre Stanford team out of the Bluebonnet Bowl in John Elway's final collegiate season—the last perfect moment for a program in danger of not surviving the new hypermoneyed collegiate landscape.

And Kapp, who suffered from dementia for the last decade-plus of his 85 years, even went out of the public eye as only Kapp could: by instigating a fight with fellow CFL alum and future professional wrestler Angelo Mosca at a Grey Cup luncheon in 2011 over a hit by Mosca on one of Kapp's teammates. He went out in full character, making memories in all corners of the football diaspora because Kapp could never really not be Kapp.

But ultimately death is still mostly for the living, so those moved by Blue and Kapp (and the Venn diagram here is two mostly superimposed circles) are moving a bit more gingerly today, looking for people who remember them both well enough for story-swapping. They played when television was already the dominant medium but still young enough to feel fresh, and when money made you rich but not generationally so. It wasn't better, but it was different, and there were fewer ways to impose one's image upon the nation as a whole. Blue, for example, was a Time cover subject in the year that Richard Nixon was Man Of The Year, just to name three other things that are no longer relevant.

Today, they are reminders that everything you know is replaceable and will be replaced, including LeBron James, Ron DeSantis, the Pulitzer Prizes, and you. The contemporary is not the enemy of the past, it's just the past that doesn't yet know it’s past. Americans in particular hate the past while longing for their idealized versions of it. Vida Blue and Joe Kapp were that past, and you appreciate them or not based on your own birth certificates—you old, irritating bastards.