Given the company's character and scale and long ethical rap sheet, it is reasonable to construe every message issued by the company formerly known as Facebook as a threat. The company surely doesn't intend this, but the story of the company's growth and success has by now been overtaken by the sum of the many, many catastrophic things that it didn't intend or just didn't anticipate or anyway didn't care enough to do anything about until people noticed that the company was facilitating genocidal regimes abroad and speeding the dissociative mental breakdown of basically everyone using their technology pretty much everywhere that technology is used. When people started yelling at the company about all that, Facebook changed its name. It's called Meta, now.

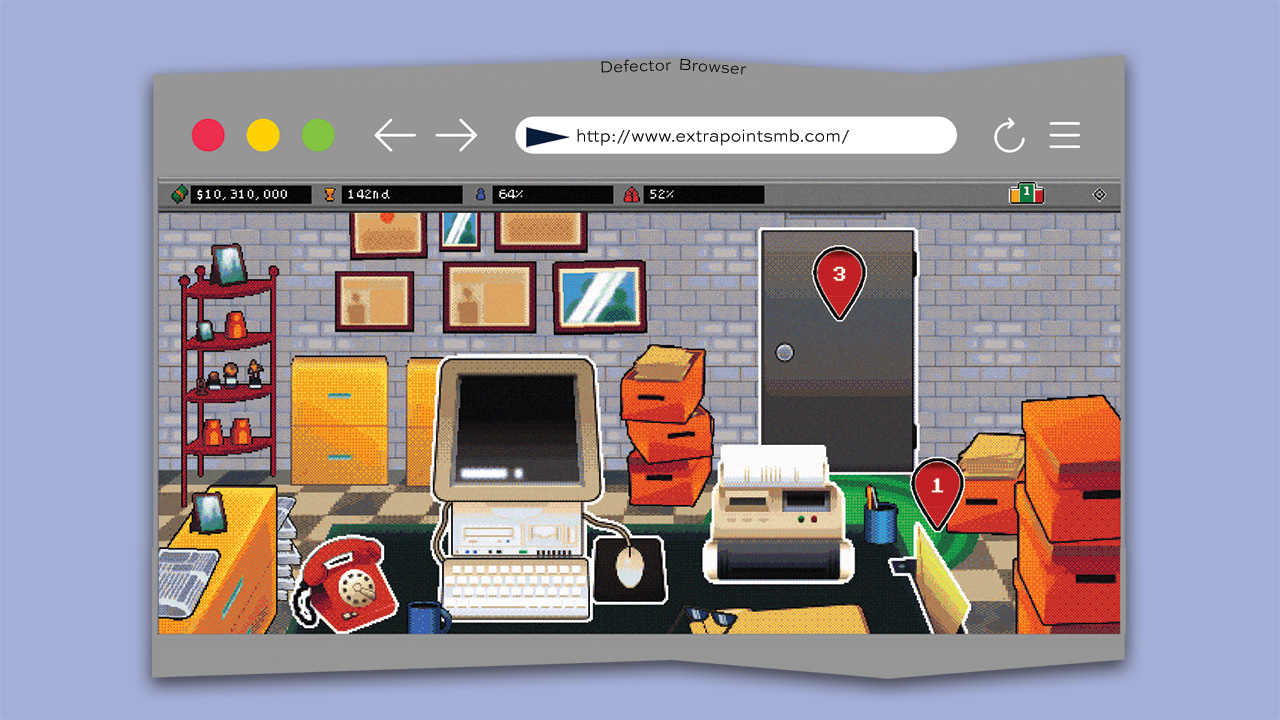

The core business, which is surveillance-driven digital advertising, is still the same, and remains preposterously profitable. Stories about the company's disastrous last fiscal quarter, in which news of declining users caused Meta's stock to crash, also noted that the company's revenues were $33.7 billion, a 20 percent increase year over year; the company turned a profit of $10.3 billion. That massive profit was slightly below projections, though, in large part because Meta spent $10 billion building out its capacities in the metaverse, a wholly virtual and not yet real virtual reality gambit. When and if ever the metaverse matches the experience depicted in the company's promotional materials, it will afford users the opportunity to experience what it would be like to attend a work meeting on their home computer, or in one of the Sims games. At some point after that, the metaverse might offer an experience that was much more nuanced without being any less virtual—the opportunity to pay in cryptocurrency (which will have been purchased with actual money) for a virtual espresso that your virtual avatar can enjoy while you yourself sit somewhere in your hilarious and unoptimized human body, wearing VR goggles and feeling faintly carsick. We are not quite there yet, though.

But if you were where Meta currently is, which is presiding over a hugely profitable but ungovernable, unwieldy, widely detested derangement engine ruled by a sociopathic algorithm and an overbearing cadre of psychotic power users, reviled and abandoned by younger users and in every sense but the most literal a haunted space station overrun by goblins and skunks, you too would want to live in the future. There was something poignant about Facebook's insistence, in the last days before the Meta pivot, that it was actually a place for people to find other people and enrich their lives in so doing—poignant because the site was quite obviously by then a place where lonely retirees turn into blood-and-soil fascists, and also because Facebook as a company had long seemed so wildly indifferent to the experience of the people using it.

The company's new presentation, though, is noticeably sweatier and darker. This is only partially because the technology that the company is touting doesn't really exist yet. The true darkness of it all is latent in the sales pitch, which amounts to an admission that the old reality—the haunted space station that generates the profits and luridly deranges America's aunts—is beyond salvaging. There are just too many goblins and skunks running around, for reasons that are not really worth going into, everyone's at fault if you think about it and there's no sense in laying blame and so on. It's regrettable, but what are you going to do? Try to fix any of it?

The ambitions of our reigning tech lords tend to be ridiculous and tacky—imagine, if you dare, a reality roughly as cheesy and brutal as ours, laid haphazardly over the top of this one, with the same people in charge—but there is also something ominous about the specific ways and places in which their powerful imaginations fail. The hyped-up rhetoric about Saving The World with the wonder-working power of cryptocurrency or other web3 gimcrackery is in some ways just familiar Silicon Valley noise, the lorem ipsum text swapped in for "to profit" under the Why heading on everything these people do. But while it is clear what these interests want, which is to continue to control a large and growing amount of money and power and impunity, it is also clear that they have moved on from the systems in which the rest of humanity is left to grind it out. That all is dying, and will be left to die. The new system will have a virtual nightclub in it, where you can buy drinks that you cannot in point of fact actually drink.

Anyway, this is all kind of a long way of explaining how Meta chose to make and air this advertisement for itself during the Super Bowl on Sunday:

The ad is absolutely state of the art, they picked a fantastic song to tie it together, and this vision of the metaverse is objectively a more appealing one than Mark Zuckerberg pitched late last year, which was a virtual space in which Zuckerberg himself slipped into an avatar that looked at most 10 percent more uncanny than he does in real life and then answered text messages. That this advertisement is so well-made, though, only serves to underline what an astonishingly bleak and hopeless vision is for sale, here. Everything you have and everyone you care about will be taken from you by forces beyond your control, the ad says. You will be surplus to requirements, first fungible and ridiculous and then literally disposable. You will lose everything. Which is notably a departure from the normal types of Super Bowl ads, which as recently as last decade were 1) Draft Horse Salutes A Troop and 2) Hot Babe Eats A Hamburger.

The ostensible selling point here comes in the back third. You may get rescued from the trash compactor, maybe. And you also might get a job, and you may, should you happen to put on the right pair of VR goggles, be able to experience a simulation of the world that you remember and see the absent friends that you miss, and so enjoy something like the life you once had, albeit all by yourself and only until the goggles are removed. That's the product, but also that's the threat.

It is unwise to read too much into any advertisement, let alone one prominently featuring Chuck E. Cheese–style animatronics. Also it is axiomatic that you will never see a commercial for anything that is actually and authentically liberating while watching the Super Bowl; that space is just too expensive, and too valuable, for anything but the institutions invested in the opposite of liberation to be able to afford access to it. But there is something infinitely bleak in seeing a company's ambitions laid out as plainly and mercilessly as this. The world we've made is going to use you up, they say, but the next one might be kinder. It's a lot easier to trust the first half than the second.