As a general rule, it is unwise to pay too much attention to anything that Stephen A. Smith is saying on ESPN. This is only in part because Smith himself isn't paying too much attention to it, although he isn't. The low thrill of watching Smith comes mostly from the way he will begin a sentence without any real sense of how he's going to finish it and then add switchbacks of blustering stagey distress and various tire-screeching caveats as needed until he figures out how to wrap things up. In terms of the role he plays on ESPN, which features him for many hours each day, Smith is probably better understood as a lead vocalist than a traditional opinion-having guy. This is both because of the outsized role that he plays in the network's programming and because most of what he's doing is more strictly a matter of making the sorts of sounds he makes than it is about saying anything in particular about anything in particular.

Smith is extremely good at that job, as it happens. As Drew pointed out earlier, Smith is if anything probably a little bit too good at it. There is no suitable counterweight for his bombast both because ESPN hasn't provided one for some time and because his brand of bombast is extremely heavy. It is a problem that so much of the programming on ESPN is grounded in the same kind of Stephen A.-style playfighting, and it is also a problem that so much of that work is done by Stephen A. himself despite his abject lack of interest or category knowledge in a lot of the things being playfought about. Smith can run through his proprietary suite of signature sounds and faces, all along his usual attitudes and gestures and perfectly on beat, on virtually any topic. This is one of the ways in which he's good at his job. But when he doesn't really know or care very much about a particular topic, those sounds and faces are all you get. The cumulative effect is deadening in the same way that, say, a radio station that only played Journey's "Wheel In The Sky" all day long every day would be.

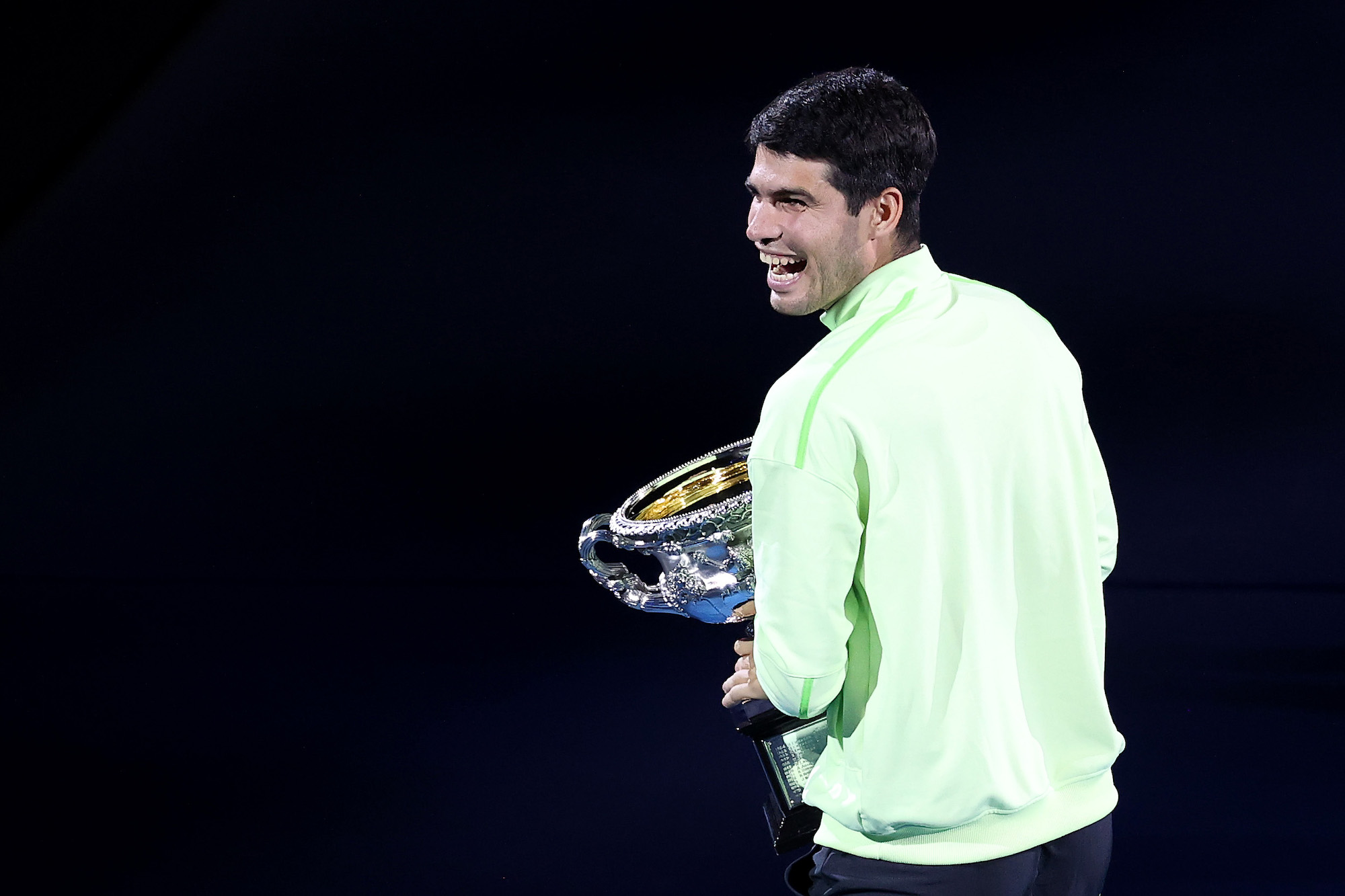

The commentary that got Smith into trouble on Monday, in which he berserkered himself into some extremely antique nativism while trying to defend the bizarre position that universally beloved sunshine superman Shohei Ohtani is somehow hurting baseball's marketability, was an example of how this sort of thing works when it really, really doesn't work. Smith doesn't really care about Ohtani speaking to the press through an interpreter, and it was easy to tell from his commentary that he hasn't really thought much about it, either. To the extent that he has, it seems likely that he knows it is in no way vital to anyone—to fans of the sport, to Major League Baseball, to Shohei Ohtani's burgeoning personal brand, to ESPN or to Stephen A. Smith—that people are able to hear him say into a microphone, in his own voice and in English, "We just battled out there today" while sitting at a folding table after hitting two homers in some desultory Angels loss to the Mariners.

But the broader shape of this failure is clearer in another bit of equally idiotic commentary from Monday's programming, which got him in notably less trouble. In that one, Smith laboriously drags the USA Men's Basketball team for losing a scrimmage to Nigeria not by focusing on anything from the game but by reading the names of the (actual NBA) players on Nigeria's roster in increasing tones of disbelief and outrage—the point of the performance is a demonstration that he cannot and will not accept that the NBA players whose names he knows lost to these other NBA players whose names he doesn't, but the subtext, in both cases, is Smith 1) admitting that he does not know or care or anyway like a thing that is in the news and 2) demanding that someone be held accountable for that.

You can critique the other team without disrespecting us. Put some respect on the flag and the mother land! Don’t forget where your ancestors came from !!!! 🇳🇬😁 https://t.co/d7B1lK0nLW

— Josh Okogie (@CallMe_NonStop) July 12, 2021

It matters that Smith is so wildly wrong about Ohtani, whose wild and broad public appeal has manifestly not been diminished by the language barrier currently preventing him from directly responding to "talk about" questions from beat reporters or swapping strained banter with an actor in a polo shirt with the logo of an insurance company on it. From ESPN's perspective, which is in point of fact not really my business or my problem, it also matters that there's no one on hand to talk about a player whose historic season has been both aesthetically and in terms of viewership the best thing to happen to the sport in ages in a way that reflects how new and fun and good his breakout has been. But while it is a bummer that "hunting for ways in which a popular sports thing is actually bad" appears to be the best the biggest cable sports network can do, it is also the approach that ESPN decided long ago was easiest and most reliable.

This has nothing to do with quality, lord knows, and whatever it has to do with ratings is probably vestigial by now. What is useful about it, from ESPN's perspective, is that it all runs on rails and is absolutely and maddeningly self-replicating. Everything becomes not just content, but a series of news cycles that are somehow both consecutive—Smith has now issued three different and distinct apologies for his Ohtani commentary—and concentric. On Tuesday morning, ESPN baseball insider Jeff Passan joined a funereal edition of the show to hold up Ohtani as "the sort of person who this show, who this network, who this country should embrace" and Hold Stephen A. Accountable in Atticus Finchian tones. On one of the slowest sports news days of the year, ESPN managed to produce hours of ponderous and self-consciously righteous programming out of its star personality's tossed-off cock-up, and to do so in a way that never really connected the cock-up in question to the actual person responsible for it.

ESPN has very consciously steered away from anything resembling actual politics in its programming in recent years, but in so doing it has managed to create programming that somehow feels ever more direly and dourly like cable news than ever before. There is information involved sometimes, but it is mostly used to make things both more infuriating and mystifying, or to justify some clock-killing filibuster or circular spat. Show after show unfolds in ways every bit as sour and recursive and deliriously un-fun as a political argument—joylessly beaten into the same rough shape, with right- and left-aligned halves of a binary respectively arguing the "I do not like and in fact am outraged by this" and "Actually it's fine" sides. The debate-shaped stuff is not really a debate, and it is all very consciously Not About Politics, although inevitably bits of the unreasoning clannishness and wary resentment and all-purpose umbrage that defines the broader political culture invariably make their way in. It is all pretty dispirited and confused and fundamentally negative most of the time, both because that is something like the default setting in most television discourse and because it has all just kind of grown in this way.

This, much more than any individual bit of hackery or hand-me-down legacy grousing, is the broader pity of all this. Shohei Ohtani is a baseball player that fans really are excited about, because he's a big happy dude who is great at what he does, because he does cool things that no living baseball fan has ever seen, and because he is a reliable font of positive energy in a sport otherwise allergic to such things. For all the things that ESPN got wrong here, for all the laziness and cynicism that let it happen and kept it going, spare a moment for the one fundamental error that supports all of it—an institution that can only talk about things in this one dreary way, and that seems somehow to have forgotten what other, brighter, broader joy there might be to find in it.