“In 20 yrs, this will all be commonplace.”

These words were first penned in 2008 by Chloe Dzubilo. A trans femme, recovered heroin addict, and long-term HIV survivor who had stayed alive more than two decades after she was first diagnosed with a virus that killed her partner in the late ‘80s, Chloe knew what it meant to play the long game, to endure trials that nobody should have to face. By 2008, she’d lived many lives: champion show-horse jumper, drug addict, lead singer of a band called the Transisters, and advocate for younger trans women and sex workers. Looking two decades into the future—still three incomprehensible years from where we stand today—she envisioned a world where trans life was obvious and indisputable. Still, she knew that the future required a fight. In a life marked by long-term disability and routine dehumanization by medical professionals, Chloe held her head high, the act of daily survival elevated to an artful refusal to accept the world’s hostile terms. The challenges she wove into her life and left behind in her art are ones we still face today, making her a critical teacher for troubled times.

Chloe made a future for girls like me to live in. When I first learned about her in 2023, stumbling upon a Visual AIDS book about her legacy, the significance of her life and its ongoing lessons for today was indisputable. More than a decade after she died at the age of 50, Chloe’s ability to persist through so many painful moments, wringing as much joy from each day as she knew how, was a revelation. I’d already spent a number of years looking back at the lessons of older generations of queer and trans elders, trying to make sense of the growing dissonance between the normalization of our lives and the ever-rising backlash directed our way. But coming into contact with Chloe felt somehow different.

Like so many trans elders, Chloe seemed larger than life. Her accomplishments, and the spirit of community-building she channeled, inspired me beyond measure. Yet the challenges she faced—so many of them a product of inhabiting a complex body that medical authorities simply refused to take seriously—were just as present in her life’s story. The hard and scary stuff that I felt got minimized in retellings of our brave and heroic elders was always critical to how I understood her.

As I’ve gotten to know Chloe better through interviews with her chosen family and visits to her archive of art and writing at NYU’s Fales Library, I’ve felt an intimacy that has at times become confounding. Chloe is so present in my life that I almost forget that she died when I was in 10th grade, years before the uptick in trans consciousness that would come to save my life. She knew others would follow in her footsteps, and she honored those she too had followed in a poem called “Dedication,” with photos of Jayne County and Marsha P. Johnson framing the title. “So here’s my humble offering for/ all the struggling goddesses yet to walk. / Things change and many things don’t.”

A new show of Chloe’s artwork, currently on display at Participant Inc. in Manhattan’s Chinatown, is a fresh opportunity to expose the world to the lessons she learned. The show, on view through July 13 [UPDATE: It's been extended one week], captures Chloe grappling with her aging body and the hard work it took to make art through debilitating pain. Yet she kept at it all the same, trusting that others would follow in her wake and knowing we’d need her voice in the future. Vibrant and enduring, heartbroken and hard-working, Chloe reminds us how intertwined all of our liberations must be. Her gift will resonate into unknown futures long after we leave this earth.

Born in 1960 in Connecticut, the youngest of three kids, it would be many years before Chloe became Chloe, the activist and artist we know her as now. While a youthful love of horses stayed with her the rest of her life, her path took several twists and turns, especially after her career as a professional horse jumper was cut short when nine horses she rode were killed in a fiery car crash in 1980, just before a competition. The next decade was in many ways a blur: stints in art school, working at the club Studio 54, and a job as an art director for The East Village Eye happened alongside a debilitating heroin addiction and the mounting impact of HIV/AIDS deaths in her community. The virus took her first serious boyfriend, Bobby Bradley, in the late ‘80s.

The Prince George Drawings, named after the apartment building that Chloe called home at the end of her life, come primarily from the last few years before her death in 2011, though several pieces look back into these tumultuous earlier periods in her life. Chloe created many of them with the encouragement of T De Long, her husband who she met and married in 2007. While it’s not part of the show, a song the two co-produced, “No Glove, No Love,” sets the tone for much of the work on view, speaking to the urgent need to make art that could help others protect themselves from HIV/AIDS. Over a bouncing throwback house track, T raps, “Can I have your attention / 'Bout what we never mention / Clarify our intention / HIV prevention.”

For Chloe, who received her formal HIV diagnosis in 1987 but suspected she had seroconverted as early as 1982 while using a dirty heroin needle, the ‘90s and 2000s were a time to take stock of earlier losses, and then to turn around and apply those lessons to supporting others. Getting into recovery in the early ‘90s allowed her to come to terms with her addiction, and no longer numbing herself allowed her to realize she was trans, offering a fresh path forward to address her own needs and turn those insights into support for others. Her activism work often came in public-facing contexts, particularly when she got on stage to sing tracks she first recorded with her band the Transisters on their 1995 record Goddesses of Pink Rock. Yet she created the drawings on display in the show knowing that the many lessons she’d learned over the years would need to be preserved after she was no longer around. There were so many moments of profound medical neglect, resilient community care, and self-revelation that she could interpret and pass along with just a few colored pens and a long storehouse of memory in her fragile, decaying physical body.

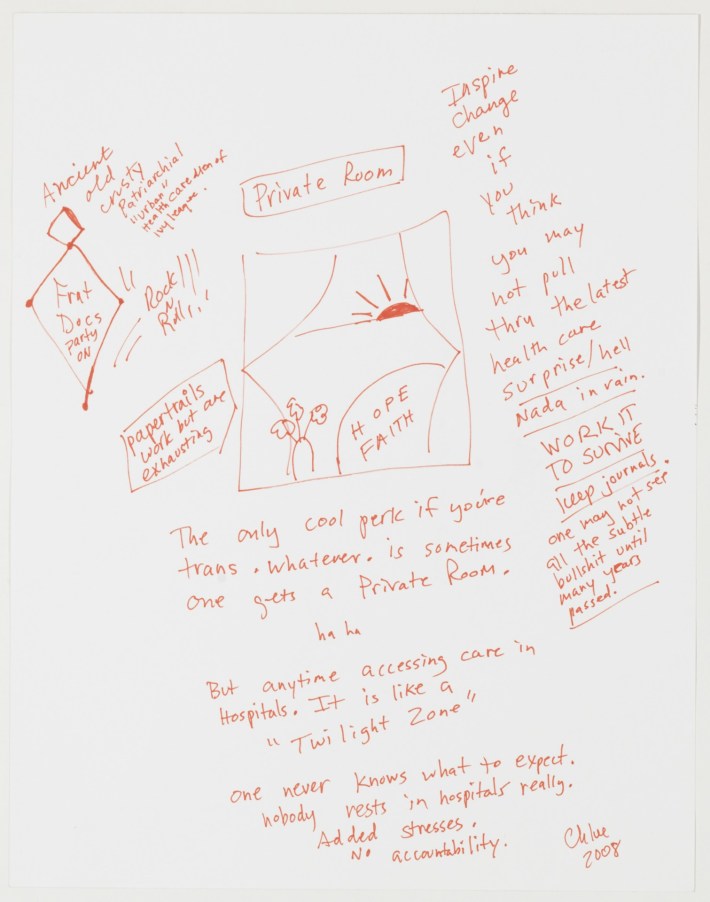

Hospitalization was a recurrent subject in her work. In Untitled (Private Room), she captures a bright orange sun, emerging on the horizon, framed by curtains, flowers, and the words Hope and Faith (her middle name). “The only cool perk if you’re trans .whatever. is sometimes one gets a Private Room. ha ha,” she wrote, able to find levity even when describing these spaces as “like a ‘Twilight Zone.’” “Inspire change even if you think you may not pull thru the latest health care surprise/hell,” she scrawled down the right-hand margin of the piece, perhaps remembering a time where she’d been subjected to cruel treatment at Bellevue Hospital—one of the city’s largest public hospitals—and then lectured a room of doctors before she even left the building, asked to speak up by a sympathetic nurse who knew she would alchemize her painful experience into support for those that followed.

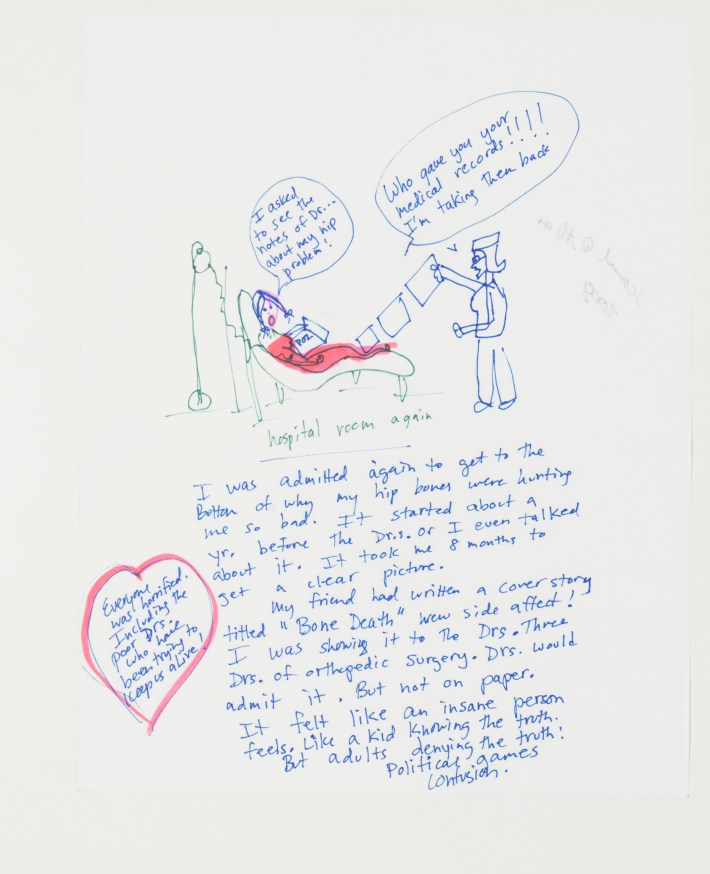

In another drawing, Chloe lies in a hospital bed, holding a copy of Poz Magazine. It’s a publication she graced three times as a cover model, full of useful information for long-term survivors like herself. In this case, she describes a cover story called “Bone Death,” which spoke to recurrent hip bone problems she faced for over a year before receiving proper treatment, still treated skeptically by doctors angry at her for trying to access her medical charts. Even as she built a devoted support team that helped advocate for her in and around these moments of hospitalization, the brute reality of hostile medical workers persisted. “It felt like an insane person feels,” she wrote. “Like a kid knowing the truth.” In these words, it’s hard not to feel Chloe standing at our side, seeing the same heightened backlash making our lives more impossible each day. She reaches out to the children who so often instinctively know they’re different from other kids, yet face increasing barriers to basic care. And she speaks to the mental illness that so many of us face—problems we experience not because we’re trans, but because staying alive as a trans person in this world means painful compromises at best, and cruelty and dehumanization that makes us crazy if left unchecked.

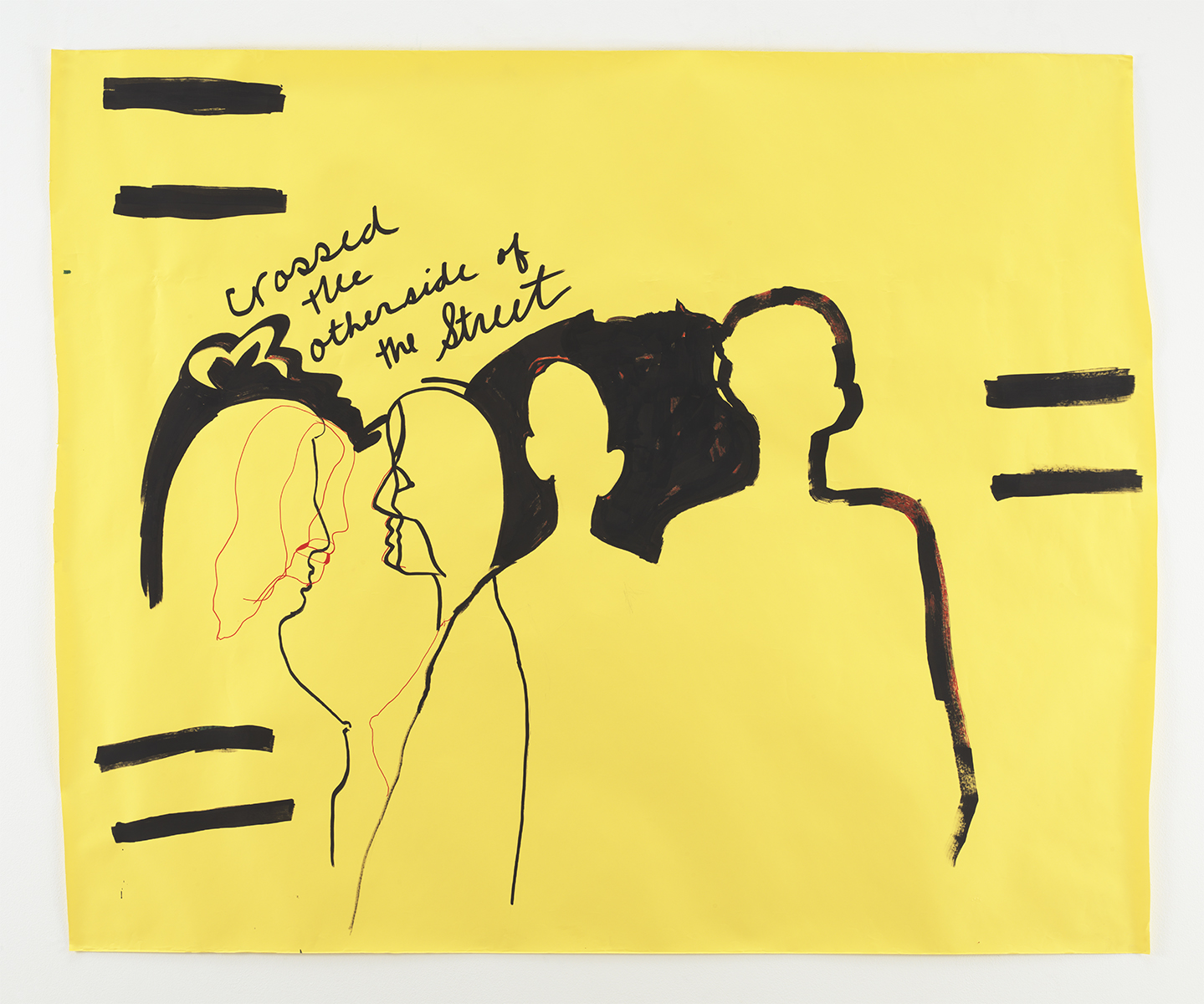

Chloe’s drawing style is unschooled and practical. Its focus is conveying anything she felt like saying, and the images, while sometimes rudimentary, still sing in a way that is uniquely hers. Among the charms in these works is her use of doubled pens or markers, a tactic that gave her more to grip when joint pain threatened to make the work impossible. The words “Stronger than life itself @ this point,” there first in purple and echoed behind in light blue, reveal the intense determination that drove her to make so much through the agony. Her focus could override what daily life often entailed: chronic, debilitating pain, hers alone to bear no matter how much help others gave her. While the doubled lines emerged as a practical choice, I can’t help but see a deeper symbolic meaning in them today: their echoing a reminder that we all make decisions about what we hope might linger on after our deaths. Chloe’s choices were always oriented toward making more livable futures for others.

Chloe was not afraid of aging. She understood the gift of getting older—of living well beyond what could have been expected of an HIV-positive trans femme who seroconverted years before reliable antiretroviral medication existed. The cumulative toll of her AIDS medication prematurely aged her body by 10 or 20 years, and she acknowledged that the medication sometimes made her feel “older than [her] grandparents.” But she embraced the effect, telling people she was five years older than she was and that she looked good for her age. Chloe refused to feel shame about her body and made space for others struggling along similar lines—an embrace that helped her advocate for street sex workers and drug users she served while working at Positive Health Project, a syringe exchange she co-facilitated in the mid-90s. Her work there, among so many other roles she played, was honored in a short film called There is a transolution, created by her adopted daughter Viva Ruiz. Old Hi-8 film footage captured her fragile and beautiful body while it still roamed the streets of Manhattan.

In a potential film treatment of her life, Chloe mused that “this film will have a very bittersweet ending and I don’t think I can handle giving that to the world.” Although they were married, T and Chloe never lived together full-time, because Chloe’s housing-voucher apartment refused to let anyone else move into the lease. That meant that in the early morning hours of Feb. 18, 2011, after being put to sleep by her friend Alice O’Malley, Chloe woke up, likely disoriented by the complex cocktail of medications she consumed, and drifted out into the world. She eventually fell in front of an MTA train around 3 a.m. The same week she died, the New York Times published a piece about suicides among combat veterans suffering from PTSD, many of them on a similar mix of contraindicating pills. It’s no wonder, then, that T has described her death as “pharmacide.” Doctors continually disregarded her unique needs, and her years of accumulated self-knowledge about her body, any time she entered a hospital setting.

Though Chloe understood that her physical body would find a painful ending, she poured plenty of herself into the world that would live on in others. Her graceful dance with the body’s finicky limits was consequential. In the Visual AIDS book about her life, JP Borum wrote, “Chloe’s art isn’t about isolated genius, it’s about being part of a community.” In a moment where governments worldwide are imperiling trans people at a speed that’s astounded even those of us who were warning this was coming, Chloe lives on in the circles I inhabit. She is one of so many elders whose legacies I feel fortunate to share in my writing each day. In a list of roles she played throughout her life, written in a spiral notebook I found while visiting her archives, I most loved No. 11: “great connector and its a fav thing for me to do :)).” What Chloe has taught me most is that while our bodies place a limit on all we can accomplish, the ability to grow our community, to expand who feels included in our company, is theoretically infinite, even after death.

At the show’s opening, I met lots of people who knew Chloe while she was still alive—friends and acquaintances with little tidbits about her to share. So too did I meet others closer to my age, a younger generation stumbling our own way forward and looking reverently to those who have come before for how they managed to survive their own perilous times. The next morning, as I returned to her archives, I flipped through a photo book full of decades-old images of so many who have welcomed me into Chloe’s still-present orbit. I felt her sun still burning bright in each of us. It’s a radiance that’s even more forceful today, and it’s there to light the path ahead, no matter how perilous the way forward might seem.

Correction (6/30, 2:53 p.m. ET): The post has been updated to correct the year Chloe Dzubilo met T De Long.