In 2006, by the time scientist Sarah Cooley finished graduate school in marine science, oyster larvae in the Pacific Northwest had already begun dying mysteriously and dramatically—unable to form shells. By 2008, the largest oyster hatchery on the West Coast suffered losses of 80 percent. Hatcheries spent thousands of dollars stamping out any possible pathogens. But scientists eventually realized the killer was not bacterial, but chemical. The seawater had become acidic, the result of the ocean absorbing some of the surplus of carbon dioxide in the air. In 2010, researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, determined this corrosive water was killing the baby oysters.

The pH of the ocean is generally stable. But when carbon dioxide dissolves in water, a series of chemical reactions occur to create carbonic acid, lowering the pH of seawater and altering the chemistry of the ocean. In the past two centuries, the ocean has become 30 percent more acidic, a shift that has happened faster than any known change in ocean chemistry in the last 50 million years. This process, called ocean acidification, has profound effects for the many lives, human and non-human, that depend upon the ocean—dissolving the homes of shelled animals like oysters and the skeletons of coral, as well as destabilizing food webs and ecosystems.

As hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest scrambled to save their oysters, Cooley remembers how swiftly the researchers around her approached the crisis. "There was a lot of all-hands-on-deck feeling in the science community," she said. "How can we how can we understand what's going on? How can we rise to the challenge?" Cooley was already interested in the science behind ocean acidification, but these community organizing efforts ignited her interest in working at the intersection of science and policy. It's where she's been ever since.

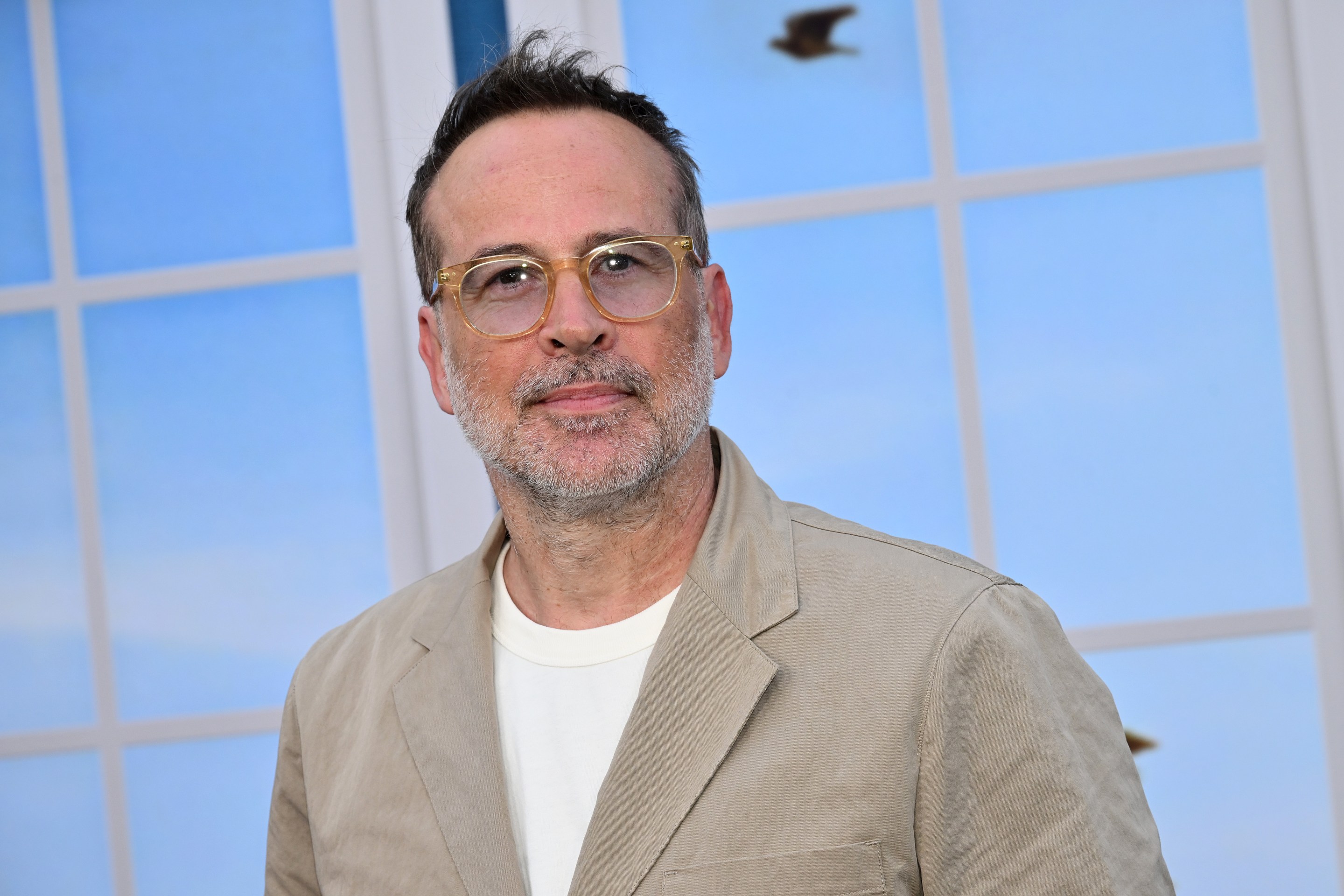

After more than a decade at the nonprofit Ocean Conservancy, last summer Cooley joined NOAA as the director of the agency's Ocean Acidification Program. In February, she was fired along with several other probationary federal workers in her small department, as a result of the mass layoffs directed by Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. This week, Cooley and other probationary NOAA workers were technically reinstated and placed on administrative leave after a series of successful legal challenges against DOGE. This means that Cooley and these workers are receiving back pay but unable to work, pending more legal wrangling. I spoke to Cooley about the threats facing our oceans, the work she hoped to accomplish in her position, and the "what ifs" of the wreckage of NOAA.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You have been working in ocean acidification for quite some time. What first drew you to that subject?

I grew up in the Mid-Atlantic. My dad had always been interested in sailing small boats, so I had a little bit of experience with that. Growing up, when I went to college, I went as a pre-med major and pretty soon I realized that just wasn't for me. I just didn't have the personality for it. I didn't get as jazzed about that stuff as some of my classmates. And yet chemistry made a whole lot of sense to me, you know? And I felt very much in the minority, right? Because a lot of people, are like, "Ah! Chemistry is completely impossible for me!" But to me, it was kind of like Legos. They clip together. They make something new. So it just clicked in my brain.

At the same time, I was always spending as much time as I could on the water, on boats. And at the end of college, I saw a lot of my classmates going on to work in the pharmaceutical industry, because that's a big deal in the Mid-Atlantic. There's a whole lot of pharmaceutical work, and synthetic organic chemistry. And I was like, "Well, I'm a terrible organic chemist. Much better at the inorganic stuff." I was kind of casting about, and then one day I realized, "Oh my god, there are chemicals in the ocean! Maybe I should think about that."

I went from feeling like a permanent student, to being like, "OK, now I've learned all this cool stuff, and I want to help bring it to other people to understand." I'm tired of just talking within this small community about change. I want to talk about, like, how is this going to affect you and me? And my neighbor? I think that came later, just realizing the interconnections of the natural world. We're actually part of that, and the things we do are super-influential on the world around us, although that worldview has not always been the western science worldview. So I think it was sort of personal evolution for me to realize that people have to be part of this equation.

Could you talk about your path towards federal service?

Being in the nonprofit space in environmental advocacy meant that you're advocating for things, often policy. One of the main targets of our advocacy when I was doing that work was NOAA's work on ocean acidification. Basically saying, "Look at the good work this this program is doing. Look at the impacts it's having. Don't you want more of that?" For 10, 15 years, I was sort of hand-in-hand partnering with colleagues at NOAA. I got to learn how policy advocacy works. I got to do some of my own.

Fast forward to the last 14 months or so. The position for director of NOAA's ocean acidification program was advertised, and I had a number of colleagues, both in NOAA and outside NOAA, who were like, Sarah, you have to apply for this. You're absolutely the best person for it. You know the program inside and out. You know the science inside and out. You've advanced the science. You can talk to policy-makers. Please apply.

I wasn't really sure. Then I started learning about the next challenges emerging over the horizon for the program. And I was like, those sound exciting. I want to be part of that. Those are things like, how can we increase the use of autonomous sensors to examine the ocean interior? How can we have that information be assimilated into global models that are going to help us forecast what comes next? How can we do a better job of marrying together what we already know with new experiments to understand the ecosystem-scale outcomes?

We know that ocean acidification is a little bit like a chronic stressor for marine life. It's something that tends to combine with other stressors to really have a harmful outcome. So ocean acidification and marine heat waves are more harmful than either thing separately. Acidification plus oxygen loss, again, can be more harmful than individually. And that's how things happen in the water, right? They're not happening individually, the way we might explore them in the lab. So just that ecosystem-scale understanding was really exciting to me. Also the prospect of a whole lot of research on marine carbon dioxide removal was also coming up. That was also really gaining a lot of momentum in industry and at research universities and things like that. And I was like, yeah, that's exciting. I think NOAA should be involved in that, at least in helping understand whether any of this is possible or a good idea. So I was like, Oh, these are exciting challenges. I would be excited to join the program and help lead through this next generation.

Could you talk about what an average day looked like for you as the director of this program?

I felt like I was really rolling in January, and I could start to plan projects. Until that happened, my calendar was fully blue every day with meetings with my staff, one-on-ones, group meetings, budget check-ins with the accounting officer. One of the things about the Ocean Acidification Program is that it really leverages and partners extensively across NOAA and outside of NOAA. And so a lot of my time was dedicated to partnership-building. I was participating in meetings and workshops with internal and external partners, understanding, well what is this agency doing on ocean acidification? How can we braid it together with what we're doing on this issue to make more than the sum of the parts?

Outside of NOAA, our program has a legislative mandate to fulfill, and so there's actual U.S. code that explains there needs to be this program and it needs to do these things. So we spent a good amount of time making sure that the work that we had planned was going to fulfill those requirements. And we did do reporting back to Congress and the executive branch on a regular timeline. Those reports have to be pretty adherent to a template, so there's a lot of work to get those reports done. Always, always budget planning and replanning. What about this new scenario? Or what about this new emerging possibility? Or, like, oh, gosh, somebody's mooring broke away, and now they need a couple thousand dollars to fix it. How can we help pay for that? Constant rechecks on how are we spending our money. How can we be fulfilling the mandate with the money that we have left?

Maybe this is a speculative question, but I'm curious to know what you would have hoped to have accomplished within your first year in this job.

I came into a program that was really, really successful and high-functioning. So there [were] no dumpster fires to take care of right away. Sometimes when you're new in a leadership position, there's all these problems. I didn't have that, so I felt like I had this charmed existence, right? I came in and I was like, all of these people are fantastic. They're doing great stuff. We had ideas to build on all of the great stuff.

As a small program that supports field operations, we have a pretty large amount of collaboration with the other programs and the ship operations activities at NOAA to make sure that our science goes off. And we had some exciting ideas about coordinating with other programs and improving scheduling future years—we call it out-year scheduling—improving that to make sure that everybody was actually getting the science that they were paying for. One of the biggest problems with a collaborative activity is everybody puts in a little money and then the ship goes. But what happens when there's a storm and working days have to get scrubbed? Whose science gets scrubbed? So we were all getting ready to work together to improve that system and make sure that the science that folks were paying for was actually being carried out, which sounds so ho-hum, but it's actually really important. It's an important piece of partnering, making sure that partners are all getting value out of the partnership.

We were starting to think about how we could fast-track the testing of new sensors on autonomous devices to go out and take the place of some of these research vessels. If you can send an autonomous underwater drone out to do your chemical testing, you've potentially saved a number of staff hours. You have maybe changed the requirements for ship infrastructure. You've made it more accessible for a lot of groups. You can maybe get into inshore areas that you couldn't before. So we were getting ready to do some work there to try to innovate and expand our sensing capabilities.

Other work that had been going on that I was excited to help continue forward was the U.S. government's initial investment in marine carbon dioxide removal research. That's something that got a lot of momentum from industry, venture capital, and philanthropy in the last two, three years. And the U.S. government did a coordinated external funding call, and money from philanthropy and from different agencies and from Congress were all pooled together into this big $23.5 million call. It funded like 17 external projects really looking at whether any of these technologies could work. Or if if they can, are they safe? Those were some of the things that I was hoping to really dig into in a big way this year. But didn't get a chance to.

Can you tell me about your termination and how that happened?

With all the buzz in the news, we all knew that that something was going to happen quite soon. My supervisor messaged me while I was on a coordinating call talking about model integration, and she said, "I'm so sorry to do this, but I can see that you're on the termination list."

I would say, 30 minutes after getting that internal chat from her, I got the same form email that everyone else at NOAA seems to have gotten, where it was basically like, "Dear NOAA employee, your skills and talents are no longer a fit." That was probably about quarter to four, and then I had to tell the rest of my team. We already had a meeting scheduled with the team at four o'clock or something. So I basically just got off on the phone, and I was like, "Hey guys, I just got fired." And we all cried together.

We all tried to figure out next steps. I tried really quickly to clear the decks and pass on as many sort of pending things or recurring calendar invites or whatever to my deputy. And so I'm trying to pass all that off and do it right. I'm trying to deal with my own feelings. I'm trying to get the team ready for like, [the] disappearance of two of us. [I] didn't even really have time to do right by my postdoc, who lost her mentor that day. We had two postdocs in the program, and they both lost their mentors on the same day, because both I and the other probationary employee were the mentors. So, yeah. That was pretty terrible. Our leadership was walking around, you know, poking heads in, being like, "Hey, I'm really sorry about this." They they did not have eyes on the termination emails ahead of time. It was a black box to them as well. I think everybody was pretty torn up. Everybody looked pretty dreadful that day.

What does your loss, and the loss of your colleagues, mean for this program? It sounds like your deputy is not going to have two jobs?

I'm super-worried about overwhelm for everybody. It's a small program to start with. Seven feds, seven contractors. It's a small program. Folks are very effective and very cross-functional. We can all lean in and help somebody else out. But we already needed help. And now we're going in the wrong direction.

Burnout is real. Dropped balls are probably inevitable.

Even though the program, you know, only received $17 million last year in federal appropriations, we were able to punch above our weight, where we're actually getting a whole lot more benefit for every dollar put in because of the effort on partnerships and collaborative goal-setting and really thoughtful division of labor between us and other programs. That takes time. It takes time and it takes mental space to sit down and say, well, OK, how can we both get our goals met, while also doing some really cool stuff in the in-between space? And frankly, when you're constantly having to respond to "What were the five things you did last week?" and "You need to scrub your website of these terms" and "You can't actually buy anything because your credit limits have been destroyed," it does not give you the mental space to actually build anything. You're just bailing at this point.

This goes back to my my sailing days, right? You are just bailing as hard as you can because the water is just spilling in over the sides. That's what it feels like. And that's what it felt like for the couple of weeks since Jan. 20. It was like, look for these terms. Scrub out these terms. Fill in the spreadsheet. Get permission for that. All of that stuff prevented so much of our real scientific work.

Could you give me an example of how this might manifest for communities?

When it comes to the program's role as a grant-maker, inability to basically get grants out the door means that that causes science at NOAA labs, other federal labs, or universities, to wither. So there's this slow-motion, downstream effect that could happen. If we have gaps in our data streams and our routine monitoring and stuff, that is going to really harm our ability to do the statistical analysis to understand what may happen. If you have a historical data set that's full of holes, you have almost no predictive power with it. The fewer holes, the more you can run analysis to anticipate what may come tomorrow and get a fine-scale prediction. So our ability to understand conditions in the near future and even the far future could really be damaged.

We're just less ready for ocean change. The less of this work that gets completed, we're going to be less ready for these things where you have a compound event, for example. Like the blob on the West Coast a few years ago. That was a huge compound event where you had a marine heat wave and you had harmful algal blooms, and it resulted in widespread effects across the whole food chain. It delayed fishery harvest seasons. It jeopardized fishermen's abilities to pay their boat mortgage. We know that compound events are happening more often and with more severity. And taking our eye off of the ingredients that contribute to these compound events means we're less ready when they happen. They're going to catch us flat-footed. And the human toll and the ecosystem toll is going to be way worse.

What are your fears for NOAA, your colleagues, and the ocean as a result of these layoffs?

It's hard to put them into words. I have just shadowy "what ifs" lurking around in my head. What I said about [how] we're less prepared in general, is what I see, right? We're less well prepared for helping people make decisions about, like, Am I going to grow old here? Am I going to take out another boat mortgage? Are we going to build a coastal industry in this city, or are we going to do it someplace else? Because we have to remember that infrastructure investments are made on multi-decadal scales. You don't build a highway without thinking about it decades and possibly even a century in advance. If we're not doing things to help anticipate what the conditions are going to be like decades and centuries hence, we're going to make some very bad investments in what choices we make today to set ourselves up for the future. Those are the things that I worry about when it comes to hollowing out NOAA's ability to look at what's coming next.

There are certain things that you're just not going to choose to do if you know that that space will be inundated, or if the coral reefs will be dead in 30 years, or if fisheries will have moved north. You'll just make different investment choices today. And I think without having that benefit of gaming out what the future might look like, we run the risk of throwing away a whole lot of money now and still having seriously harmful consequences as a result.

Being a climate scientist, I'm a scenario-planner, right? I think about scenarios. I think about what happens in a high-emissions world, a low-emissions world. So that training kind of leaks into, I'm thinking about what happens in a high-NOAA-wreckage world or a low-NOAA-wreckage world. I'm trying to figure out what exactly that future looks like. And I think that's what we're all trying to do right now. Maybe as the dust clears and I get a cooler head about all of things, I'll be able to kind of figure out what elements must we retain so that we can have something to raise out of the wreckage in the future. But it's the uncertainty. It's like taking everything that has been set up so deliberately over decades, and just like throwing it against the wall to smash on the ground.