The way Amanda Cronin sees it, her environmental education began at the farmers' market in her hometown in New York's Hudson Valley. She marveled at the sheer abundance of produce, so much so that, at age 11, she became the market's on-camera personality. Every Saturday, she would go to the market and interview a farmer about their growing process, such as how olive oil becomes "extra virgin." She tasted her first oysters and learned about the distinction between organic foods and other green-washed labels. Eventually she read Michael Pollan's The Omnivore's Dilemma, which cemented the idea that "our food system is broken and Big Ag is really corrupt," she said.

Cronin started working directly for the planet at the age of 13. She interned for an organization called iMatter Youth, which encompassed youth-led organizing for the climate crisis. "Because I was so young, I couldn't really be a full-time employee," she said. iMatter Youth's mission was to train youth activists across the country to make changes at a municipal level, exposing Cronin not just to the power of environmental policy, but the concept of environmental justice: the idea that everyone, regardless of race, class, or any other identity, deserves the same environmental protections and benefits. The idea just made sense to her. "I grew up in a very privileged place where I had access to clean water, clean air, a backyard to roam around in," she said. "I didn't have to worry about living near a power plant, or have direct environmental harms."

In 1992, President George H.W. Bush established the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Environmental Equity, which was the precursor to the Office of Environmental Justice. The office was later renamed by President Bill Clinton after he issued an executive order acknowledging that minority and low-income populations bear the brunt of the effects of pollution. In 2022, President Joe Biden merged three EPA programs into the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights, which would oversee some of the $60 billion allocated by Democrats in the Inflation Reduction Act for environmental justice priorities.

On Earth Day in April 2023, Biden signed Executive Order 14096, calling on the government to take action against environmental injustice. The administration was actively staffing the Office of Environmental Justice, and a month later, Cronin joined as a program analyst. On Jan. 20, President Trump rescinded 14096 and all other environmental justice orders as a part of its plan to repeal diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. Cronin was placed on an indefinite administrative leave on Feb. 6, meaning she is unable to work. In March, Lee Zeldin, the Trump-appointed EPA administrator, announced plans to eliminate all the agency's environmental justice offices.

I spoke with Cronin about the bipartisan benefits of environmental justice and listening to and rebuilding trust with historically marginalized communities. (Cronin spoke to me from her position as an individual, not on behalf of the EPA. The day after we spoke, Cronin received an official Reduction in Force notice.)

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

When did you realize that you wanted to work in some capacity around environmental justice?

I did experience Hurricane Sandy. That was traumatizing. We were without power for about two weeks. Luckily, my grandma lived nearby and she had power, so we ran and lived with her. But if she hadn't been nearby, we would have had to assess our options. That was definitely my first direct exposure to the reality of the climate crisis. Later, when I was older, I learned that the folks in New York City—particularly in neighborhoods that are primarily people of color, like Harlem and the Bronx, and those areas—that people were without power for much longer than two weeks. That they couldn't stay in their buildings, at least while breathing healthy air and having access to basic utilities, and a lot of people really didn't have another place to go. ... Who gets harmed the most? It's usually those people who are the most vulnerable or historically overburdened classes.

How did you decide to pursue a career in public service, working around this issue?

My first experience out of college was to do a Fulbright scholarship in the Buenos Aires province of Argentina. I chose Argentina, and was lucky enough to get sent there. Fulbright is also screwed, which we don't have time for today—that's another story. But I'm really grateful for that experience. I chose Argentina because they are an interesting composite comparison for the United States in that it's also a massive country with lots of natural resources, as economists would say, but as environmentalists would say, a lot of natural beauty and really vibrant, biodiverse ecosystems. I saw a lot of comparisons of, oh, California has wildfires, and the province where Lionel Messi grew up has wildfires. We are dealing with a lot of the same issues.

The university where I taught [English] was, no joke, right across the street from an oil refinery for the biggest gas company in the country. ... The smoke stacks were so obvious from my first day. I saw the campus building, and then looming right over were these villainous-looking—to me, anyway—smokestacks pumping out fumes.

I don't know who exactly to attribute this to—because it's been a quote that's been repeated—but often at EPA our administrator would say environmental justice is where we live, work, play, and pray. The experience of someone's full life and what they do in the course of a day should be encompassed. I would add "study" too, because often young people are forgotten. These students didn't have any choice but to attend university here. It was the number two university, like the Yale of Argentina.

I designed a survey for the campus community to ascertain what their knowledge level was of the refinery and how it might be impacting their health and public health in general in the neighborhood. ... A lot of people were motivated to do something, but they didn't know exactly what they could do. This gas company is pretty much [the] dominant company. It's as if Exxon was the only gas station in all of the United States.

That experience in particular was what led me to apply for jobs in environmental justice, and I was lucky enough to get hired by this new office at EPA.

I was reading through your resume that you sent me, and I clicked on the [EPA's] link to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and realized that the page has now been deleted. So I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the remit of the council.

This was just the top of the top experts in environmental justice, public health science, local government workers, and environmental policy who were particularly passionate about environmental justice. And also the fathers and the grandfathers and grandmothers and mothers of the movement, including Dr. Robert Bullard, who is a really famous individual, as well as Dr. Peggy Shepard, Dr. Beverly Wright. These are all giants in the environmental space.

They were assembled—about 24 to 30 members—to advise President Biden and Vice President Harris's environmental justice policies and actions. They helped do that by having these public meetings. A large part of my job was helping us prepare for these in-person meetings; assemble all of the folks who came there. What happens at public meetings, just like for a lot of other policy actions, is you have a public comment hearing period. So these work groups would be formed based on the comments that we received. We made sure to have these meetings in environmental justice communities.

We heard the most heartbreaking stories. Oftentimes, it would be the person who was facing, whether it was like a personal health issue like cancer or their family member, or had lost their home, or was seeking to get relocated because their home was being threatened by either eminent domain threats or that they live near, for example, Cancer Alley, Louisiana, and they just couldn't survive living in their family home any longer. My first meeting, I was not prepared for the content of these kinds of comments. I cried. I really couldn't hold back tears, because this is really just devastating. It's a failure of government, in my point of view, and I think a triumph of the Biden-Harris administration was creating this office because this had just been ignored in the past.

Our success was in having these public meetings, having online webinars, and just consistently communicating with people what we were trying to do, and also having them lead in advising us on how to do our jobs in the best way that we could. Because our office was stacked with really experienced people. A lot of people who had never worked in government before, like me. So they brought a wealth of experience, but we always tried to approach things with frontline communities, which are the communities directly impacted by the climate crisis and by environmental injustices [and] know what they need best. There's a term for this called meaningful engagement. Meaningful engagement looks like listening to these communities who face this every single day, instead of prescribing from the top down. It may sound simple in theory, but because these communities had been ignored at best, or actively had laws passed against them in the past ... the trust that had to be rebuilt between the feds, us, and all of the people that we were seeking to help for the first time in the agency's history, was really the work that had to happen.

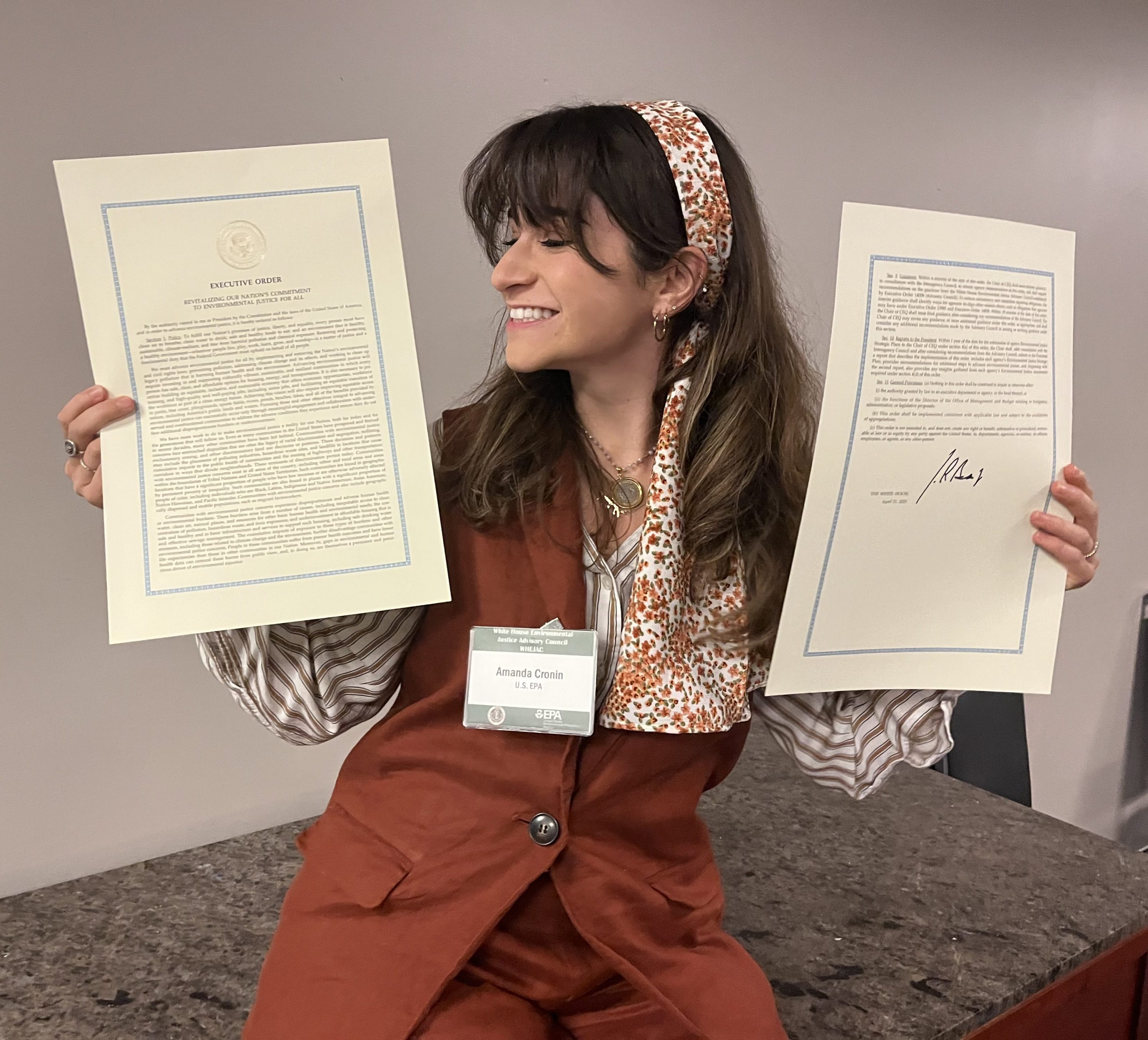

At these meetings, work groups are formed on specific issues. Then after months of meeting and writing, the deliverable that would come from these work groups was a report of recommendations that would then be delivered to the president's desk. And these could be 10 recommendations to—I think there was one that reached 100—about how to reform either existing or proposed new policy or programs. Examples of that were the Justice 40 initiative, which promised 40 percent of funding to be earmarked for environmental justice communities. That was something that was promised in Biden's Executive Order Number 14096, which is not on the White House website anymore ... I have to laugh to keep from crying, because it was a really, really big deal that executive order was actually passed. It was passed on Earth Day of 2023, and I joined the agency, as you know, in the next month. So I just felt I was coming on this tidal wave of momentum of getting the President to say "environmental justice matters" in the Rose Garden with all of these great activists who had dedicated their lives, a lot of them in their middle aged and older years. To have this moment with the president was just, I mean, more powerful than you could describe, for a lot of people who got to attend that ceremony.

Could [you] talk about what it looked like to be carrying out these larger ideas and missions on a day-to-day basis?

A typical day working from the office was commuting to the EPA headquarters building. It's a very grand building right next to the White House around all these other agencies like the FBI. I had a few pinch-me moments taking the metro there among all of these professional suit-wearing people thinking, wow, I am the government.

It's a lot of relationship-building and a lot of convening of people from all over the country. So I did a lot of Zoom webinars. I had one monthly call that I co-hosted with my colleague, Dr. Larissa Mark. That was what we called an all-states call, which is just shorthand for every department of environmental quality office at the state or regional level, and every EPA regional office—there's 10 regions—was invited. We would share out updates, and be the microphone or the loudspeaker for Environmental Justice Policy and Program updates that had happened over that previous month. It's not very sexy, but important, and especially important because it hadn't previously existed in a legitimized call from actual EPA staffers. So I was glad to be able to help with that. We did the same thing for tribes and Native/Indigenous peoples.

Not only were we soliciting public comments from members of the public, but also from these [White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council] members themselves. They were nominated because they are experts in their own experience. One example that comes to mind is an activist Vi Waghiyi. She is a Native Alaskan women. ... She was the leader of Alaska Community Action on Toxics. Her family had the most cancer cases I had ever heard of from an individual. Every time we were on a Zoom for even a work group meeting, she was mourning the loss of another member or caring for someone else.

She was specifically trying to get the Army Corps of Engineers to clean up these abandoned military sites that are all over Alaska that have really harmful, toxic waste that is leaching into the water supply, the soil, the air, and harming every aspect of the ecosystems, but particularly the animals and plants that they in their culture use for subsistence living and that they have for generations. That they rely on for substance and sustenance, because buying food in Alaska is quite expensive and difficult to ship there. And it's also just their way. I'm sorry to say that no recommendations report was issued to target that issue. She beat that drum the whole time she was on the council, to her absolute credit, and it's a shame, because it was such a small window of time that this council existed. There was only so many things that could be accomplished. I think there was about 10 recommendation reports that were ultimately submitted, which is impressive in the span of almost two years.

I am really proud of helping get those recommendations—which in some cases were like 80 pages long—to the finish line and convert oftentimes very heartbreaking, devastating stories into actionable policy items. Going through that translation process was the bulk of writing these reports. How do you turn the story of someone's cancer story or mold growing in their home, into "the Department of Energy needs to revise this law"? A lot of the members [weren't] fluent in that kind of language. So that was the the kind of expertise or help that we could provide as government officials who are more familiar with those laws.

Of course, lot of the members of the council are familiar with [the National Environmental Policy Act] and the Endangered Species Act and a lot of other laws against their will, because a lot of people who are on these councils got involved with this work because it was a matter of their survival, not because this was their dream job that they've always wanted to do. So I want to make clear that I don't want to fetishize this work. I do say that it was my dream job because I was so excited to be able to do something about this. But I see that I had a choice in taking on this job, whereas a lot of other people really do not.

Could you talk about your experience of being fired.

Tomorrow is Earth Day, and I've heard rumors and threats about Administrator Zeldin passing all sorts of policies and firing more people on that day just to make it burn a little bit more for us. As well as I've heard whispers about executive orders being passed tomorrow. So it very well could be that tomorrow I'll be fired. [Editor's note: On Earth Day, Cronin and her colleagues received a Reduction in Force notice announcing the EPA's intention to fire or reassign them starting on July 31.]

Our environmental justice staffers at EPA worked under the Trump administration in the past and were able to accomplish great things. And I see his agenda and his attack on environmental justice as pretty ironic because a lot of his voters are folks who live in historically marginalized communities. Poor folks who live in rural communities who feel that they're being ignored by the government is exactly the kind of people that we were trying to help.

Here's one example: Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, Republican, actually sent a letter to the EPA inquiring on a status update for an organization in his community from his constituents. I think that organization had either applied for a grant or had been awarded a grant, but they hadn't received their money yet. So their representative, Mike Johnson, wrote on their behalf, asking the EPA, "When is this money coming? My constituents really need this money." So we have concrete evidence of this is a bipartisan concern. There is really nothing political about helping people who have tried to deal with inequitable systems in the past. It's a real shame. Not to get too political, but I see that it could very well come back to bite Trump and his other staffers in the future. Because I think we're seeing in real-time how his voters and his supporters are dealing with the consequences of policies like pausing the dispersal of these grants. Because a lot of communities were expecting them to make payroll, to build climate resilience hubs for the next flood or the next hurricane.

What are your fears for the communities that you were working with, or for the nation more broadly, and for the natural world amid these cuts?

It can be a matter of life or death in a lot of these communities receiving attention, support, policy change, funds from the EPA versus not. Or active, malicious policy against them could be a matter of someone surviving or not, or having to leave their home and try to live somewhere else.

I don't want to keep using the same words, but it's hard to find more negative words to describe this kind of stuff. The climate crisis is only getting worse. We see on the news and face ourselves new extreme weather events every passing week, it seems. The frequency is just greater and greater. We didn't only focus on climate change in our office. But that was absolutely one of our priorities, was to create resilience hubs and create policy and create resources to help environmental justice communities prepare for these kinds of extreme weather events. To speak broadly about the most immediate impacts is that these people are the most vulnerable. Of course, we're all vulnerable to the climate crisis. That scares me the most, because it is so both immediate and unpredictable and we really were doing something about it and were being so creative with the approach. I hope that sometime in the future, we can resurface all of this good stuff, all of these programs and great ideas, and somehow we could pass a new huge spending bill.

The government employs maybe more people than any single entity in the country, and yet there is still this prevailing notion of a government worker as being this dusty, stodgy, kind of boring, pencil-pushing person. I think the Office of Environmental Justice and Civil Rights is kind of the antithesis to that, because we were a group of diverse people, both of background and experience, and there was just so much energy towards doing good for the people. People had such a sense of pride for their participation in public service. They did not take that responsibility lightly, and that kind of passion aggregated in one place was so powerful and so cool to be participating in. I just hope that we can somehow get back to that. It's gonna take a long time, sure. But I hope that our faith isn't too damaged in these systems to get back to that place.

If you have lost your job as a result of ongoing government cuts and are interested in speaking with me for this series, please contact me on Signal at simbler.88 or simbler@defector.com. I would love to hear from you.