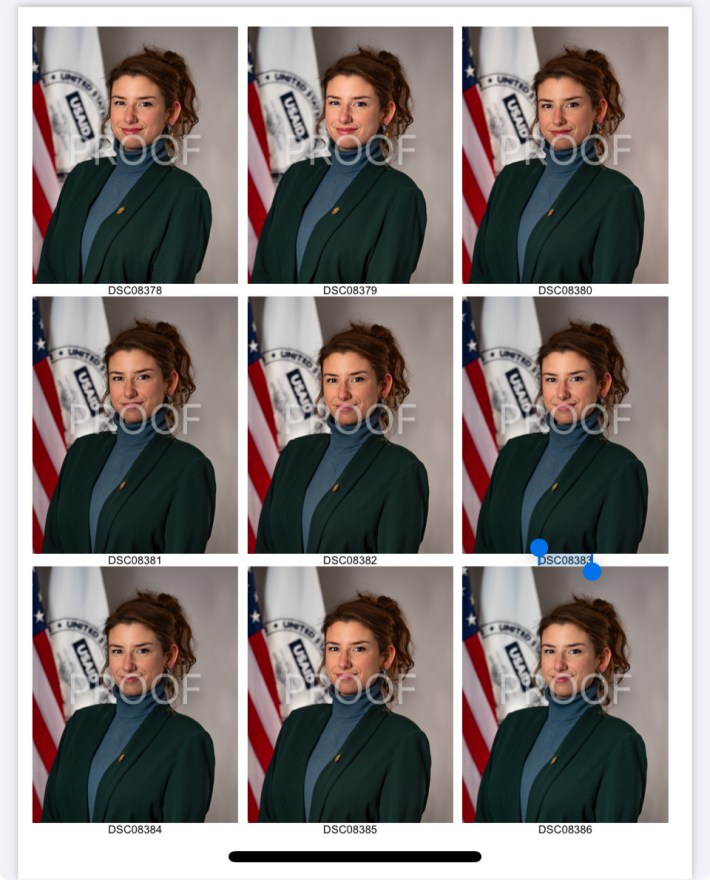

In August, Charla Burnett moved from Michigan to Washington D.C., with her 5-year-old son, for a new job. She joined the first class of USAID Science for Development fellows, working on energy subsidy reform, AI data center placements, and expanding access to renewables around the world. The post would be a stepping stone to full-time employment at USAID as a foreign service officer, which was Burnett's ultimate dream. Burnett was set to take the Foreign Service Exam in February. She took her official USAID portraits on Jan. 11, posing in front of the agency's flag, and soon received the watermarked versions. To Burnett, this felt like a milestone—one she'd been working toward for 13 years. "I felt like I finally made it," Burnett said. Weeks later, she was fired. Ten days after that, the administration canceled her exam.

Hoping, at least, to retain one artifact of her time in federal service, Burnett emailed and asked if the photographer could send her the actual headshots. But he never emailed her back. Burnett suspects he was also fired. "Complete breakdown of communication by everyone, because everyone just got let go," she said.

To Burnett, her firing represented a larger betrayal: not just taking away a dream job, but also reneging on a promise to lower the cost of her education in exchange for serving the nation. Burnett was the first in her family to graduate from a four-year college, and her father never graduated from high school.

She had been working for nonprofits, government organizations, and public universities since getting her PhD because she was counting on the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program to eventually forgive the substantial debt she accrued from graduate school. The federal program can erase student loans if you make 10 years' worth of monthly payments while working for the governments or nonprofits. “This was, at the time, the only way I thought I could get an education and better myself and my future family, my son,” Burnett said.

After Burnett was fired, she had to put her loans in forbearance, which pauses payments. “I was prepared to take on that debt because I was made a promise," she said. “I feel like they’ve violated our agreement.”

In March, Donald Trump signed an executive order that aims to restrict PSLF eligibility for any organization the administration disagrees with, such as nonprofits working with immigrants or queer communities. For now, the program remains unchanged. Experts suggest this order is likely illegal and will be challenged in court. But the administration appears intent on rolling back Joe Biden's various debt relief and repayment plans. So even if Burnett wanted to go back into the nonprofit sector, she worries there these organizations would no longer qualify for PSLF.

Burnett was fired on Jan. 27 as a part of the mass layoffs directed by Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. I spoke with Burnett about the global need for energy, the American dream of working your way out of poverty, and what it feels like when the government breaks its promise to you.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell me about your path towards public service and when you became interested in international development.

I grew up in Lansing, Michigan, to a single mother who benefited a lot from public services like SNAP food assistance. I wasn't quite sure what I wanted to do for university. I was actually an art major. I got into the art institute in San Francisco and I really wanted to go, but my mom was quite hesitant and worried that we wouldn't be able to afford a $70,000-a-year tuition. The cost of living in San Francisco would be too high. So she encouraged me to go to community college for two years. I took a class on environmentally friendly textile designs, and it kind of just changed my life and our understanding about our environment and how we as humans impact our ecosystem.

I transferred to Michigan State University. This was around 2008, 2009, and the government was just starting the PSLF program. They're like, hey, if you go do 10 years of public service and make all your minimum payments, we will forgive your student loans. This started getting me thinking, how could I be most valuable to public service and to the world at large? Let me be a little bit more uninhibited with going the distance and becoming a scientist and really pushing myself. So after I graduated from MSU with a degree in global studies and human rights, I went on to do a master's degree at the School of International Training in conflict resolution and peace building.

I used to teach at the Refugee Development Center in Lansing. So from there I pivoted and I did some research with World Learning and SIT in Liberia and refugee camps on the border of Cote d'Ivoire. From there, I took a one-year position at the United Nations Relief and Works Agency in the West Bank. Both of these refugee camps were primarily funded through American international foreign assistance. I'd seen the great work that USAID was doing. And I said, that's my end career goal. I want to get to USAID. So I've always worked for nonprofits, intergovernmental organizations, or public universities so that I could continue to contribute to my PLSF payments.

When we talk about whether or not we're investing in our families and whether or not we're having children, this has a lot to do with the debt that we incur just trying to live life and also to educate ourselves and get out of poverty. I'm extraordinarily lucky. I was able to obtain a career that has really gone beyond anyone else in my family's ability. I've literally changed—for my son, I have a 5-year-old son—changed his life and our ability to move, which is the American dream, right? If you work hard, then you're going to have more than what your parents did [before you]. Those were the value systems that I think are really inherent in what it is to be an American. After I finished my PhD, I moved back home, because I was having my son, to Michigan.

I still wanted to move to D.C. I knew my home was going to be at USAID, and that was my end [goal]. So last year, at this time, I had applied for the Science for Development fellowship, which replaced the American Academy of Science fellowship here at USAID. This was our inaugural cohort. There were 19 of us, and we all got placed in different departments across USAID. I was placed in the Energy Division.

Our energy division really had a robust portfolio of different projects, whether it was regulatory reform in the energy sector, so ensuring that regional regulatory bodies are using best standard practices and ensuring accountability and transparency. We also worked on competitive renewable energy auctions in countries to attract private financial investments, and that were most cost-effective [meaning they had the best return on investment for Americans].

Everyone at USAID was very optimistic. We are a non-partisan institution, and we're definitely willing to adapt the strategies and the languages that our current administration [wants us to use]. My advisor had been through the administration's first presidency and was able to implement it in what he thought was a very successful way. So everyone was extremely optimistic until about January. My cohort of fellows was one of the first to lose their contract.

We were told we had two hours to leave and get everything from our desks, and that we were let go without pay. Unfortunately for some of our fellows, they were coming directly out of their PhDs and didn't have a career behind them. So that meant that they couldn't file for unemployment. I was lucky that I had enough experience and time between my PhD and this fellowship that I could apply for unemployment, which honestly, for a lot of people here in D.C. where the rent's pretty high, is really life-saving. Two of the individuals that were in a fellowship were actually in the process of actually starting a full-time position. So both of those automatically lost their new jobs. Then one of those women was pregnant, and she went into early labor the next day after.

Could [you] talk about what specifically about USAID attracted you to the agency?

I think I have a lot of pride in being American. I think that oftentimes USAID is the first line of soft power and defense that we have as a nation. My mom taught me a long time ago you attract a lot more bees with honey [than with vinegar]... We might have a really strong military, and that can do a lot in regards to defense, but our real success in the world is that soft power and the way that we can extend an olive branch to others around the world, and a mutual understanding that democracy is beneficial to the people, to human rights, to our economies, to our welfare. So for me, USAID was the real mechanism for which we did that type of work. Me, I wanted to be a Foreign Service Officer. I wanted to be a diplomat. I was actually set to take the Foreign Service exam in February, and they canceled that two days before.

I really think when you meet people abroad, there can be this assumption that maybe people don't like us, or they want what we have. But they don't. They want to build their own country side-by-side, and when we help to facilitate that, they see us as an ally instead of a competitor. And that's extremely important to ensuring that we have a thriving ecosystem of an economy where we diversify our economies and they become more resilient as a whole to shocks and disasters.

Talk a bit about the role of GIS in green energy development.

Geographic information systems are tools and hardware that can be used to geolocate all different types of things, whether it's people or it's assets [or infrastructure]. So in the context of energy solutions, essentially it is an extremely powerful tool in the fact that it can help us optimize the use of our energy assets. For instance, I was working on [a project that used GIS] to be able to monitor and evaluate where different [energy infrastructure existed], what level were they being used, and then whether or not, for instance, they need to be replaced. A lot of middle- [and low-] income countries, they might have had a paper map at one time, maybe that got destroyed, maybe it got lost, but using geospatial technologies allows us to actually map them, upload them to a cloud system, and then share that data very quickly and efficiently across different regions.

It's very important just for understanding where these specific things are, [and] how we can make sure that it's being distributed effectively. But then you can also integrate social economic information so that we can ensure that these investments are ... getting to the people who need them the most. So it also has to do with equity solutions as well.

When you say that you're geolocating energy assets—and this is a very basic question—but does that mean oil or hydro, these sources of energy?

It's used across all different energy sources. You could be having an oil and gas company using remote sensing and GIS technology to assess where methane gas is leaking. Sensoring technology with GIS are able to monitor and evaluate the type of oil and where it's located underneath the ground, how deep it is. All of those are used [in] geo-reference technologies, but also the placement of wind farms compared to Earth observations, LIDAR data, so we can understand where is the most effective placement of wind farms. Or solar—where the best places that are going to actually harness all of that solar energy? And then if we don't have batteries, where do they need to be spaced so that they can help to take that generated energy and move it towards communities?

Energy is everything. I think that that's what really captured my attention, because I had been offered another position under the President's Malaria Initiative, which would have been great work. Malaria has horrible impacts on communities all over the world. But with energy—if we didn't have energy, we won't have hospitals. You won't be able to perform surgeries. You don't have energy. We cannot keep the lights on at schools after dark, so students get less time in the classroom. We don't have street lights. A lot of times, communities are far more dangerous for women and children [without adequate lighting]. So really, [the] energy component is the base of all our development as a global community. Without electricity, there isn't much we can do.

Could [you] talk briefly about what an average day looked like for you on the job?

USAID hires other organizations to implement projects. So much of what we do at USAID, unless you're working directly in the humanitarian space, where you're implementing disaster management or post-conflict management, you are overseeing subcontractors. ... Our job was really to manage those projects and ensure that they comply [with] federal regulations.

Some of them were not international development specialists, right? They might be a construction company that's building a school, but they've never worked in Kenya before. So we have to advise them on those intercultural nuances that are needed to be successful in implementing those projects. We're kind of their guide through the development process and because of federal regulation, unless for some reason we can't manufacture something here in the United States, everything that we purchased, all of the materials, all of the food, comes from U.S. businesses.

I wanted to ask if there were any projects in particular that you were excited about doing at your job.

The USAID YouthMappers program was a project that they've implemented in, I think it was 40 some-odd different countries. But essentially what it did is it engaged college students. What we would be doing is then going and soliciting students who are interested in GIS work, but maybe interested in energy or vice versa. Then we would have them go out into their communities and map those assets, the infrastructure for [utilities]. And so they would go and they would take their phones, and they would download an app, and they would mark exactly where a specific asset was, so if it was an electrical pole, and then they could say, "Okay, this electrical pole is in good condition. Oh, this is where downed power lines are." Essentially, they're saving those companies that are investing in the infrastructure and money [through the data the students collect.] And they're getting them interested, both the company and the students, in the use of GIS in the energy sphere.

That was going to be my big project that I was interested in doing in the course of the two years while I was a fellow. My goal was to get hired in and stay in the Energy Division and continue to work in this field.

Is there's anything else you wanted to say about your experience of being fired?

I think I was fired from one job when I was, like, 16. I was working at a Big Boy. I was waiting tables. And I had another job at the same time, so I never was without a job. I've never been unemployed [and never] this long. And definitely never fired from a job in my career as an adult. And I've been working since I was 13 years old, so it's been really difficult for me to kind of figure out my next steps. Obviously the market here in D.C. is very difficult for everyone applying to jobs.

I don't want to leave D.C. It's my home. I've actually never felt more at home anywhere else in the U.S. in my life. My son's here. I live next door to his school. He has friends here now. So I'm trying really hard to gain employment. I've applied to over 60 jobs. I've had multiple interviews. I actually had a job lined up the next week after getting fired, but then the federal government cut funding for that specific position because it was a subcontracting position.

I do know that we're sliding into an economic recession, and it's hard to really gauge whether or not we're going to have jobs or an economy to support the reintegration of—just at USAID is 33,000 federal employees.

I wanted to ask about PSLF, and if you could talk a little bit more about what that breach of contract was like for you, and also if there's any kind of recourse that you and other folks would have.

So I didn't have to take any private loans. All of my student loans were Pell Grants or federal subsidized or unsubsidized loans. I kept it that way on purpose. That meant that I worked a job the entire time I was going to university so that I could pay for everything as much as possible. I was very excited after my PhD to start paying those loans back. And I paid every payment on time. Right now I have had to put them in forbearance. So that means interest is accumulating. Interest always accumulates on our student loans.

To me, it shouldn't be a bipartisan issue. This is something that's great for our economy. But it seems to be that when the pendulum swings and we get different certain types of value systems within the government, that they want to take that offer away from us. When you're talking about money, in no other business would you be able to make a promise to people and get them to take out student loans and it not be a scam. And it really feels like a scam, because I could have easily not invested in that, went and got a job in the trades. ... But instead, I was like, I want to take out these loans and become a scientist and really move the bar for innovation in a way that those types of jobs can't necessarily do. I did that based on the promise of the PSLF forgiveness, because my family couldn't support me with paying for my college education. And now that's been ripped from me. And it really makes me feel let down and also kind of abused a little bit by my own government in a lot of ways. Because I was lied to.

Was [there] anything else about your work or your firing or the impacts had on your personal life that we haven't had a chance to talk about?

It's not just me. My son's father also lost his job. I've seen this numerous times—we're not together anymore, but it's still very hard. He just moved down here to be with his son.

He was also working for the government?

He was working for nonprofit organizations [whose] funds come from the federal government. A lot of federal workers meet their partners when they get here to D.C. ... The level of uncertainty when both parents have lost their jobs is so frightening, because people have leases right? We can't just leave D.C. after we signed a lease. We have to continue to pay or we default on those. And then we might have to file bankruptcy. We could get sued. Imagine if you had a health crisis during this period of time.

A lot of times there's a lag in payment for government contracts. This happens all the time. So when they cut funding to all the programs, they didn't just cut the new funding. They also never paid back their contracts. So we have subcontracting companies that haven't been paid for work that they've done back in September, October, November, December, and I'm talking [large sums of money.] $20 million is owed to one of the companies [subcontracted to USAID.] So their whole life has been dedicated to implementing these projects for the federal government, and now they're out of their business.

Then they've also hired all of these organizations and people abroad in these other countries, and in some of these countries, it's illegal to default on your debt, so they had to literally call them in the middle of the night and say, "You need to get out of the country. I'm sending you your tickets right now." They've had to leave their cars, their animals, to get out of the country. So this has far-reaching impacts that I don't necessarily hear [about] in mainstream media, about acts of not paying our debts as a country, in countries where the price you pay for not paying your debts isn't just bankruptcy. It's violence and imprisonment.

If you have lost your job as a result of ongoing government cuts and are interested in speaking with me for this series, please contact me on Signal at simbler.88 or simbler@defector.com. I would love to hear from you.