When All Elite Wrestling hosted its initial episode of Dynamite roughly a year ago, the weekly show seemed to promise more than just two new hours of wrestling to watch on Wednesday nights. It would be that, too, but the ambitious scale of it reflected the scope of the company’s aspirations. Two well-received pay-per-views prior to that October 3 episode of Dynamite had shown what the promotion could do, but the weekly show indicated what the promotion wanted to be. You can’t be a big-time promotion in this era without a good weekly show, and AEW wanted to be big-time enough to challenge WWE for the North American wrestling throne. As AEW prepares to celebrate a year of Dynamite with an anniversary show on Wednesday night, it’s time to consider how exactly this newest contender is doing in its quest for ubiquity. So far, it's both broadly positive and obviously incomplete; the stuff that works really does work, but there’s still a ways to go before the promotion can deliver on the innovation promised by AEW's brass.

One of AEW's selling points was that it would try things no “major” company ever had. To that end, it has mostly failed, albeit with a giant, coronavirus-shaped asterisk. As the company heads into its anniversary show, three of its four major titles are held by former WWE wrestlers: Jon Moxley (f.k.a. Dean Ambrose) holds the world title, Cody (Rhodes) has the TNT Championship after winning it back from big man Brodie Lee (Luke Harper), another WWE vet; the tag titles are held by FTR, formerly the underappreciated The Revival. Sure, AEW has given a title shot to Orange Cassidy, an avant-garde fan favorite who simply could not do what he does—or, really, exist in anything like his current form—in any other major promotion, and there are storylines in the undercard that certainly point to a more distinct product plan. At the very top, though, all that wild innovation has instead looked like one proven commodity after another.

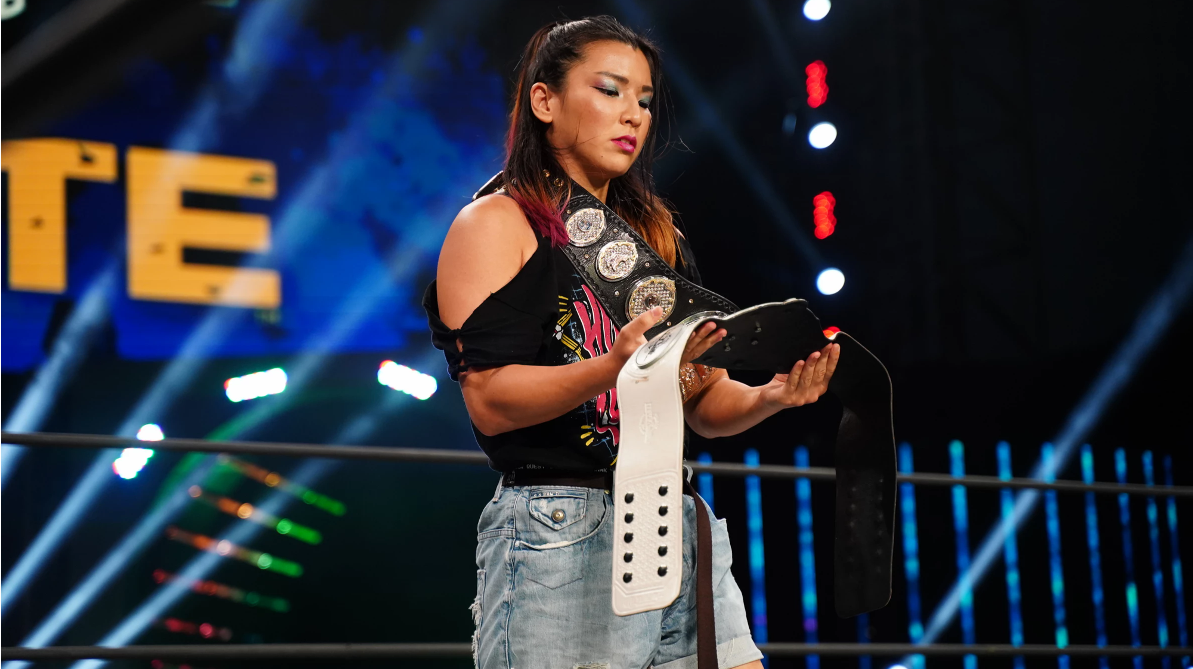

The one exception is, unfortunately, AEW’s biggest failure to date. The AEW Women’s World Championship is currently held by joshi wrestler Hikaru Shida, who is as close to a perfect wrestler as exists in 2020. She’s got the style, the wrestling chops, and all the babyface energy anyone could ask. The problem is that, for all of its talk about inclusion and bold new thinking, AEW has flubbed its women’s division in some frustratingly conventional ways.

The main problem here is the same one that has hobbled major companies’ women’s divisions forever: time. On average, the women’s division in AEW gets one or maybe two segments per Dynamite episode; on some episodes, that number is zero. Shida has been stuck doing squash after squash for the last few months as champion, which is a waste of both her talents and the show's screen-time, while the division's storylines have reliably been overshadowed by multiple, dynamic feuds between the top male stars.

To make things worse, the biggest breakout star from AEW's women’s division hasn’t even won the title: Dr. Britt Baker (DMD, don’t you know?) was pegged to be the top babyface in the division when Dynamite launched, but she was poorly received and so did what all poorly received faces should do. The doctor turned heel, and became instantly more entertaining. Back when there were fans to rile up, her shtick was standard “trash talk the city you’re in” fare, but in the absence of fans Baker has developed a memorably cowardly troll persona and given the women’s division its first real character.

And character matters a lot. The wrestling in AEW has generally been top-notch across the board, but the reason performers get over when everything around them is uniformly good is that they stand out. That's how Orange Cassidy and Darby Allin and the Jurassic Express all became popular before coronavirus hit, and how idiosyncratic wrestlers before them have gotten over forever. The pandemic has been an obvious obstacle for the company in this regard, as it’s harder to develop fan favorites with no fans in attendance. But the effort that has been expended in the various men’s divisions just has not carried over to the women's division, despite AEW EVP Kenny Omega’s deep involvement and investment.

Almost all of AEW’s shortcomings ultimately resolve to the same source, which is that these men do not have a ton of experience booking different types of wrestling. Most of AEW's most important decision makers come from pro wrestling's most consistent sources of high-quality matches, New Japan Pro Wrestling and Pro Wrestling Guerrilla; Cody came from WWE’s midcard. They have shown some care to the women’s division, and towards an undercard that doesn’t revolve solely around the same main characters—Chris Jericho’s interminable feud against Orange Cassidy, for instance—but the promotion's day-to-day tends to be more aligned with what the market wants: wrestlers that people know, doing cool things. That’s how a promotion can get two women’s matches on the debut AEW pay-per-view, 2019’s Double or Nothing, or a Women’s World Championship match at the inaugural Dynamite, and still have the division feel like a failure. It's clear that AEW cares about the women's division as a calling card, but it hasn't put in the week-in, week-out work to make it into a true foundational piece of the program.

AEW’s general move away from its initial “wins and losses matter” mindset has been another disappointing bow to convention. Weirdly, the women’s division has mostly kept using it, although that’s likely because there are no compelling undercard wrestlers to shoot up to title contention. The men’s division, on the other hand, has used tournaments and battle royals to rocket worthy challengers up the ladder. It’s fine to operate like this in order to put on the best shows, but the approach is 180 degrees different from AEW's initial hype surrounding how differently its title shots would be determined. This is the risk of making such bold promises at the outset—fans might start expecting to see it, and while AEW has given those fans plenty of good stuff to watch, it has fallen short in terms of looking like nothing else and providing airtime to under-represented elements.

Does that make the company a failure? Absolutely not. It’s been around for a year—17 months if you start with the aforementioned Double or Nothing—and these can very much be filed under growing pains, the painfulness of which is exacerbated by the state of the world in 2020. Nothing is over, and the Anniversary Show could function as a giant reset button. After all, all four belts are up for grabs, with some of AEW’s most charming stars on the challenging side: Big Swole will take on Shida for the women’s belt, Best Friends will challenge FTR for their tag titles, and their best friend Orange Cassidy will take on Cody for the TNT championship. (Moxley will defend his world title against Lance Archer as well, but that feels like a more traditional match between a fighting champion and a monster heel challenger.)

If any of those belts trade hands, and actually lead to some new stories and matches, then AEW will be nicely set up for a second year that could be very different than its first. It's worth noting, too, that AEW already does a lot of difficult stuff well. The promotion does a good job of highlighting wrestlers on its Dark show, which airs on YouTube on Tuesdays; that’s where you can see more women wrestling and more undercard stories being developed. Of course, the audience for Dark is significantly lower than that of Dynamite on TNT, so the company will have to figure out a way to bridge those two worlds beyond highlight packages.

The training wheels are off, and sometime soon AEW will start to risk its initial goodwill if it can’t incorporate some newer, fresher content. This is particularly true given that their chief rival in the time slot, WWE’s NXT, has had a quietly riveting summer and, so far, fall, particularly in their own women's division. This is AEW's sophomore year, and the steep learning curve of trying to navigate a new program, during a pandemic, will at some point start to feel less like an explanation and more like an excuse. One can only hope that AEW has taken the lessons of their maiden voyage to heart, because being unique is the one thing they can always lord over their titanic competition. There's no reason AEW can't pull it off. They just actually have to be unique to do it.