A few weeks ago while on vacation, my partner and I took a bus to Porto Venere, a town on the Ligurian coast of Italy, to see a famous grotto where infamous bisexual Lord Byron used to swim. The grotto was spectacular, nestled in a cove of of clear blue water with shoals of small black fish, below a distinguished old castle and a distinguished old church. It was so beautiful that it made me wonder if I should become a poet, before quickly coming to my senses. I loved the grotto so much that I came back to spend the whole day sunning on the rocks, drinking a herby spritz, and admiring the wildlife. And that is when I noticed the seagull nest.

Unbeknownst to us, we had arrived in Italy during peak seagull baby season. From my perch in Lord Byron's grotto, it seemed as if a perfect square had been cut out of the cliffs. Inside the square, the distinctive gray fluff of a seagull hatchling poked out, watching all of us human swimmers as its two seagull parents switched off positions—one guarding the babies, the other hunting for fish. I had never seen a seagull nest before, and I couldn't imagine a more perfect place to raise my fluffy little chicks.

I wondered how long the nest had been occupied. Did Lord Byron see generations of seagull chicks fledge in the cliff hole? Do seagulls engage in turf wars over this perfectly guarded and picturesque cliff hole? With a cliff hole this opulent and level, a seagull would be a fool not to nest there!

Sadly, with no physical ability to scale the steep and rocky cliff and no tools nor knowledge that would equip me to understand how long the nest had been occupied, I was left to ponder this question indefinitely. So when I saw this week's home, which was first published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, I was astonished to learn just how far back in history some nests go.

The first thing to know about this nest is that it is very difficult to get to—that is, if you are a human. The nest is in a national park in Patagonia, tucked away in an ignimbrite cliff, which is a type of volcanic rock. There is a road you can drive on to get close to the nest. "But then you have to climb over the edge of the cliff and then you rappel down 10 feet and you swing into where the nest actually is," said Matthew Duda, an environmental scientist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada, and an author of the new paper. "It's very difficult to get to."

If you are a bird, no problem. You can fly there!

At a glance, the nest might not look like much. It looks like a dingy gray donut made of stone with some dust gathered in the middle. But this donut is not made of stone. This donut is made of poop. And the poop, or at least some of it, is over 2,000 years old.

If you personally are not interested in living in a 2,000-year-old poop donut, that makes sense! This nest is not for you. It is for Andean condors, which are tank-like raptors with an Elizabethan ruff of white neck feathers and a ten-foot wingspan.

The birds don't construct nests, but choose secluded spots on skyscraping cliffs to keep chicks away from the claws and mouths of predators. Any extraneous material brought to or dropped by the nest, such as feathers, scraps of prey, or feces, would normally be blown away by the wind. This makes Andean condor nests extremely hard to track down. "You might show up hoping to find these condors, but they'll be soaring way above you," Duda said.

But thanks to a prime cliffside location, the poop donut offered proof that a lineage of condors had been returning to a nest over thousands of years. "This is a really special spot because it's in a grotto," Duda said. The donut is located below a stony overhang, which shielded these scraps for thousands of years, allowing them to sort of congeal into a mound, which the birds pushed aside to make room for a chick at the center—hence the donut shape. "Really special circumstances," Duda said. "I don't know of any other donut like this."

After the researchers sliced a wedge from the donut to analyze the nest's contents, they refilled the ring with rocks to maintain the donut's cozy shape. The donut slice languished in a freezer for several years before Duda picked it up. "I thought, well, this is fascinating," he said. When he took samples from the bottom of the donut, tests revealed they were both more than 2,000 years old. "I was looking at those results and I thought, something has gone wrong here," Duda said. He took 10 more samples, which revealed the donut had been occupied over a period of 2,200 years. The poop did not accumulate as neatly like a tree ring, but piled up in distinct periods that revealed more details about the condors who once called this donut home. If you move in here, every bowel movement could contribute to science!

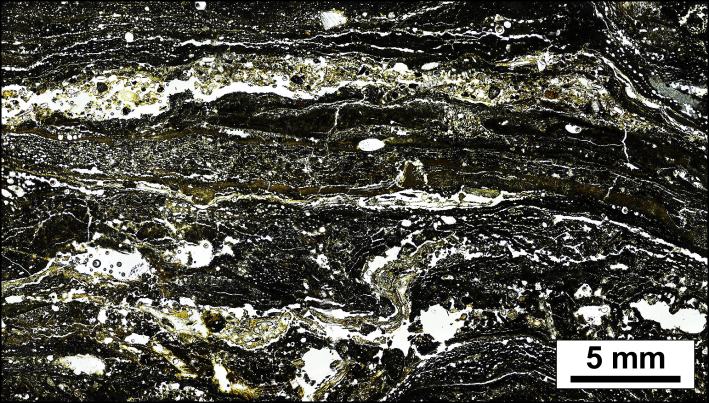

Duda found the cross-section of the poop donut aesthetically pleasing. "It looks like the glaze of a potter's pot," he said. "It's got this really beautiful wave structure to it." Do you agree?

The donut slice also revealed this cliff was not always prime condor real estate. About 1,650 to 650 years ago, condors practically abandoned the nest, which the researchers attribute to increased volcanic activity nearby. The region would have been shrouded in heavy ash, which would have driven out the large herbivores that Andean condors feed on. But that's what you get when you move to the Andes! Volcanoes, volcanoes, and more volcanoes. And it's much easier to flee a volcano when you have wings, which you certainly need if you want to occupy this home.

The poop also preserved an archive of colonialism. In the oldest layers of the donut, the researchers found traces of the condors' original food: guanacos, wild, llama-like herbivores. But after European colonization, the condors switched to scavenging on livestock, such as sheep and cattle. But the birds aren't picky. "They will eat anything that's dead," Duda said. "They'll find a corpse of a sheep and then they'll stick their whole head in there. And then when they're feeding their young, they will regurgitate it on them."

In more recent samples, the researchers also detected higher levels of toxic mercury and lead in the condor feces. Although the birds are scavengers, they are occasionally shot by farmers seeking to protect their livestock or poisoned inadvertently after feasting on prey shot by lead bullets. Just about 10,000 Andean condors remain in South America, a number that is declining.

Even aside from the threat of people, the Andes is a harsh environment for a home. Rainstorms, windstorms, and the occasional volcanic eruption could all cause Andean condor chicks to die. But the poop donut's perfect, grotto-adjacent location shelters young birds from the elements. As an Andean condor chick, there may be no better place to hatch, fledge, and eventually fly away. "It's protected. It's high up on a cliff. There's no disturbances. There's no predators. There's no scavengers," Duda said. "It's just such an ideal spot that they can continue to come back over years and years and years." Doesn't that sound nice? My ideal home also has no predators, but unfortunately does have a lot of scavengers.

You may be wondering: Is ancient poop less stinky, more stinky, or equally stinky as fresh poop? Duda has the answer. Totally untouched, the poop donut's smell "is not as bad as you could imagine it being," he said, noting the poop has spent thousands of years drying up. But the donut slice was dense, chalky, and delicate. It crumbled to the touch, releasing putrid clouds of dust that actually did smell crazy in there. "It is, like, poop-like, but not," Duda said. "It smells more like something has gone sour."

With all this information, you may be wondering—how much could a nest with this much history still be on the market? Well, it's not for sale. Wisely, Andean condors do not engage in capitalism nor believe in private property. Good for them!

This week's nest is in an undisclosed location to protect it from the prying hands of people. If you try to buy or otherwise interfere with this perfect nest, it is not unlikely that an Andean condor will feast on your remains until you, too, are a part of the poop donut.