Before the Mets' game against the Houston Astros on July 18, 1986, Tim Teufel passed out cigars in the team's locker room. The platoon second baseman was rejoining the team after staying behind in Connecticut to be with his wife while she gave birth to their first child. Teufel, who was by all accounts a stand-up guy, made for an odd cultural fit with a Mets team that would become legendary and was already renowned in that moment for high-intensity dirtbaggery; Jeff Pearlman's 2004 book about the team, The Bad Guys Won, revealed that Darryl Strawberry frequently bullied Teufel by calling him "Richard Head" until Teufel confronted him. "There’s a breaking point to every person in their pride and character and who they are," Teufel told Pearlman. "No man is going to just sit there and be a marshmallow."

That Friday night, Teufel went hitless in three plate appearances in a Mets loss. Later that Friday night, after closing time and a couple of hours into Saturday, Teufel was beaten up by a bunch of Houston police officers outside of a bar called Cooter's Executive Games And Burgers; Ron Darling, who pitched seven strong innings in that loss, was thrown through a plate-glass door by another member of Houston's police department, and two other Met Cooter's patrons, Bobby Ojeda and Rick Aguilera, were also arrested. That happened around two in the morning on Saturday the 19th, and the players were held for 11 hours before being released on bond. This was a long time ago. Darling is in his 25th year as a television analyst; the former Cooter's is now a TJ Maxx parking lot; it has been a decade since the son whose birth Teufel stayed behind to witness wrapped up his five-year minor league career. But another way to know how long ago it was is that the news that four Mets players had been booked after fighting the cops didn't break until the next day: Sunday, July 20, 1986.

I can only assume that was when I heard about it. Hearing things about the Mets—learning them, committing them to memory, carrying them around with me for the rest of my life like a bunch of old lunchmeat in a backpack—was already a passion of mine as a young child, and while the specifics of the story did not really stick with me, the names of the four players arrested and especially the name of the place where they were arrested really, really did. Not the Executive Games And Burgers part—the concept of an "executive burger" is both some of the Most 1986 Shit Imaginable and fairly in keeping with what Cooter's, an upscale club that reportedly let pro athletes drink for free, was aiming for.

Like the other stories that emerged about that team at the time, the Cooter's incident arrived to my eight-year-old self as an unparseable broadcast from the world of adults. Whatever it was that my heroes were doing at Cooter's, at 2 a.m., against some indeterminate number of off- and on-duty cops, I am sure I rounded it up to inscrutable grown-up stuff and decided that it was not really my business. If I asked my father what an "executive burger" was, I don't know what he would have told me; I have to imagine I'd remember the answer. There was a lot of this, as I recall, just a whole lot of me seeing some sort of headline and thinking, That doesn't seem like something that Lenny Dykstra, my hero and also exactly the sort of adult I aspire someday to be, would do.

The broad strokes of the story, in the early reporting, mirrored what was in the police report: Teufel tried to leave the bar with an open bottle of Heineken, was prevented from doing so by two off-duty police officers working security at Cooter's, who were in turn prevented from doing what they were trying to do by Darling. The police claimed that Teufel elbowed an officer and kicked him in the crotch, and that Darling grabbed another by the throat. At some point after that, other Houston police officers—a cab driver put the number at seven to Dave Anderson of the New York Times—arrived and beat Teufel up.

Teufel and Darling were both charged with felony assault on a police officer, and their teammates were charged with misdemeanor hindering arrest. "The four players involved in the incident would like it made public that they feel they were unduly assaulted by police personnel on the scene," their attorney, a big-ticket Texas criminal defense attorney named Dick DeGuerin, who would later defend Robert Durst on a murder charge in Galveston, told the New York Times. "One of the players, Tim Teufel, was in fact severely beaten by the police." Cooter's soon began selling T-shirts that read Houston Police 4, Mets 0. They were still selling briskly when the Mets returned to Houston in October. "I almost laughed when they came out with the T-shirts," Darling told Gordon Edes of the Los Angeles Times. “It was done in a tactful way, not malicious. Compared to some of the press we’ve gotten elsewhere, it wasn’t so bad." Edes later mentioned that the shirt was "a favorite" of Roger Clemens.

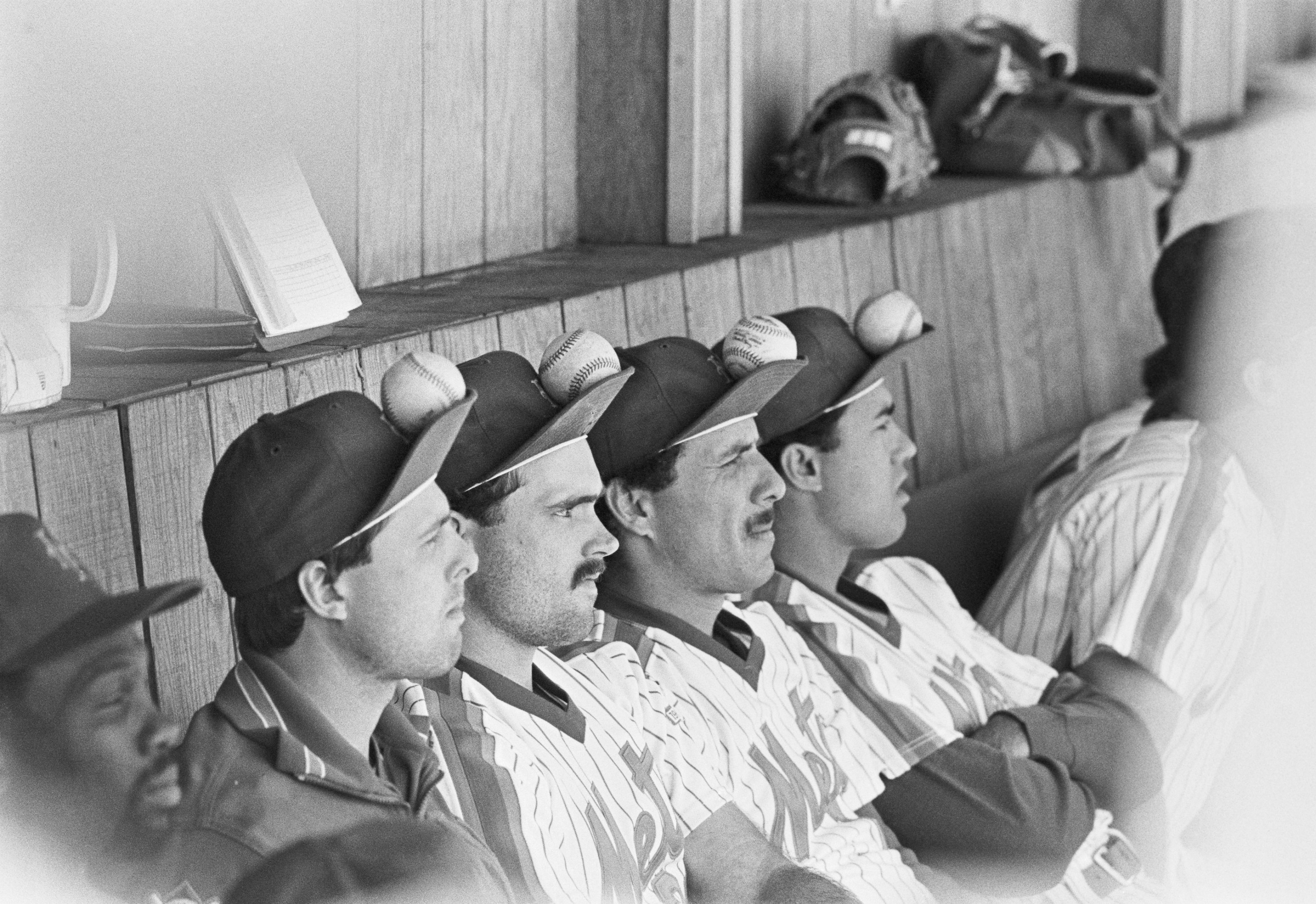

The players were fined by manager Davey Johnson. "My main rule is 'don't embarrass me or the ballclub,'" he explained. "This is embarrassing to the club, to their families and to me." Their teammates responded more or less as you'd expect a bunch of Reagan-era degenerates to respond. When the players arrived in the clubhouse after posting bond, the Times reported, "adhesive tape had been placed vertically on the four players' locker stalls, making them look like jail cells. A beer can and a plastic cup, labeled 'tequila,' was sitting on each player's stool, along with a bar of soap, a razor, one cigarette and a book of matches." In the 2021 30 For 30 about that Mets team, Ojeda gets emotional at the memory. "It was like we were heroes," he said. "We were heroes to our boys." All four players were indicted in August, with a trial date set after the season; the charges against Teufel and Darling were serious—the maximum penalty was 10 years in prison—but a plea deal reduced them to misdemeanors and dismissed the charges against Ojeda and Aguilera altogether.

Immediately after the incident, DeGuerin said that the arrests "would not have happened anywhere but Houston," and Johnson echoed that assessment. There are a number of things that this could mean, none of them especially flattering, but because Houston was in fact where it happened, I found myself returning to Cooter's. That Mets team partied not wisely but too well, and was never terribly abashed about any of it; in Keith Hernandez's diary of the 1985 season, published in 1986 as If At First..., he rhapsodizes about the strip clubs of Montreal and describes getting 86'ed from Johnny Bench's sports bar in Cincinnati because "when I get drunk, I get loud." Long before Pearlman wrote about the Mets bullpen's grossest dudes—they called themselves The Scum Bunch—sticking boogers on each other in the back of the plane in The Bad Guys Won, it was clear that this was a team with A Big Personality, and that part of that personality was "acting like a bad person." Some of them really were, and others were dealing with addictions that would make the rest of their lives difficult and sad; most of them were just rich and young.

There's no mystery to any of that, really, and it might be that there is no real mystery to Cooter's, either. It closed in 1989; Ray Ratto, who was covering baseball while Cooter's was open, remembered it as a place that players went to and sportswriters didn't, as part of an unspoken détente that left some places off-limits, or just off the record. (He also noted that this did not stop players from going to sportswriter bars whenever they felt like it.) But if it is not difficult to imagine the sort of place that young rich people went to get fucked up in 1986 in the broad strokes, the specifics remained obscure. There is enough going on in the name—you've got both "Cooter" and "executive," plus games, and additionally burgers—that it confounds the imagination.

In 2010, someone posting as Brunsonpark08 started a thread on the website HoustonArchitecture.com. He had just finished reading The Bad Guys Won, laid out the broad strokes of Cooter's role in the story, and asked users if they had any memories of the place. "If this already has a tread [sic], I apologize," Brusonpark wrote. "I just wanted to know more about Cooters."

Over the course of dozens of messages left over the next 15 years—the most recent is from April—numerous people aimed to help Brunsonpark out. There was some debate over whether it was a "kicker" or "kickerish" bar, with the consensus eventually settling on the assessment that it was, as one user put it, "a kind of cooler disco type." (Another remembered it as a "Butt Hut," which he clarified was "a place to meet women.") Most agreed that good times were had there. One patron remembers being denied entry because he was wearing "white K-Swiss sneakers;" another remembers winning a bench-press contest there in 1989. In 2017, a user posting as Mr. Cooter's identified himself as having been a manager there for 13 years. "I knew about 2,000 people by first names and was in every fight that took place including both times the Met's gave us a try," Mr. Cooter's wrote. "It was the best 13 years of my life and should you have any questions I would be happy to answer them, I will not however, divulge private things about the wealthy that frequented Cooters, as they have a right to their privacy." He ends his note, "Sincerely, Mr. Cooters, a name I earned." He has not posted since.

The picture that emerges is not necessarily coherent vis-a-vis what type of place Cooter's was, but supports the idea that it was the sort of place that ballplayers might have wound up feeling themselves enough that mixing it up with some police officers would not have felt entirely out of bounds. The most recent message in the thread is from a woman who discovered "a pair of tiny red shorts that had COOTERS HOUSTON on the bottom" when going through some old clothes. She had some good times there, as well as at five other places she names. "Houston dance clubs in the 80’s were the ultimate parties!" she concludes. "Too much cocaine, sex, and getting crazy!" That still does not explain what an Executive Burger is, but it feels close enough.