In a containment lab in Wellington, New Zealand, Kat Bolstad considered the squid cube. It was the size of a keg and had been frozen solid since January, when it was hauled up during a research trawl in fishing grounds to the east of the country. The squid cube was not a cube of squids but rather one single cube-shaped squid, whose flaccid body had been folded into a rectangular fish bin and subsequently stored in a freezer. It chilled there until June, when Bolstad, a deep-sea squid biologist at Auckland University of Technology, was ready to unbox it.

"It's not the first squid cube," said Bolstad, who has seen many cubes of varying sizes and species in her line of work. But it certainly was a very special squid cube, comprising the carefully pleated body of an entire giant squid, meaning a species of deep-sea squid in the family Architeuthidae. When giant giant squids are caught in research trawls, their bodies are too big to be cubed, i.e. stored whole in a standard 50-liter fish bin. Those true giants are often frozen in pieces or "whole, in a gigantic sort of sausage-shaped, very large package that has to be moved by a forklift," Bolstad said. But this giant squid, a young female, was just small enough to fit inside the fish bin and become a cube of her own. As Bolstad described the arrangement of the squid's body: "It was like a cat curled up for a nap inside the fish bin."

About twice a year, Bolstad's lab sojourns to Wellington to thaw squid cubes and other squidsicles (frozen squids that bear somewhat less resemblance to regular geometric shapes). The city is home to the marine collection facilities of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, or NIWA, which slowly accumulates and freezes creatures collected on the institute's research cruises. Some of the squids are frozen for months before their dead flesh experiences warmth again. And the quality of the carcasses can vary a lot depending on the squid's journey from the deep to the surface. "Sometimes you get a really beautiful one," Bolstad said. "Sometimes it looks like somebody sneezed in a tray."

Successfully unboxing frozen squids can be a race against time: Bolstad's lab and NIWA staff members have to complete their work before the flesh starts to rot. Although a single, finger-sized squid might defrost in a half-hour, larger squids can take an entire day. And a squid compacted into a cube also does not defrost evenly, running the risk that the outside of the cube could rot while the inside is still frozen solid. A few years ago, Bolstad had to thaw a squid cube of a colossal squid—a different species altogether, and the largest invertebrate on the planet—weighing more than a thousand pounds. Colossal squid tissue is more delicate than giant squid tissue, so Bolstad's team defrosted that colossal cube in a bath of sea ice to keep the dead squid in relatively pristine condition.

This June's squid cube was less fussy, defrosting in air overnight until the researchers returned to unfold the half-thawed cube and run water over its body to help it along. "We did have visions of it, like, unfolding and then slithering to the floor and just having a horrible disaster in the morning," Bolstad said. But the squid cube cooperated, and the next day could be fully unrolled and restored to its tentacled, 21-foot-long glory.

Scientists do not often have the chance to examine giant squids. The animals are very large and live in waters thousands of feet deep, making it fairly unpredictable when one might turn up. For a long time, scientists could only study Architeuthis from squids that were discovered dead on the shore, dead in the water, or were digested or regurgitated by sperm whales, according to a 2013 paper in the American Malacological Bulletin. Recent advances in deep-sea trawling and underwater camera systems have given scientists a little more access to the elusive giants.

Still, it's rare to come across a giant squid that has yet to reach full size, Bolstad said. Scientists are still sleuthing out the life cycle of giant squids, a cephalopod whose babyhood is somewhat of a black box. "There's a size below which specimens are basically unknown," Bolstad said, adding that there are records of "fairly small" mature males. But female giant squids get much larger: Whereas a mature male might top out at around 32 feet, a mature female can grow as long as 42 feet. Mature male giant squids produce packages of sperm called spermatophores and implant them into the skin of a female giant squid. But the researchers found only tiny hints of eggs in this particular cubed squid, meaning she was an immature female who had not mated.

Curious to learn what she ate, Bolstad's team gently slid out the squid's nearly gallon-sized innards. This week, the researchers plan to defrost the squid's guts—which are sadly not cube-shaped but roughly oblong—and examine what half-digested creatures and undigested microplastics might lurk inside. With any luck, they'll find a few parasites. Many parasites in the ocean have to move through different unique hosts throughout their life cycle: After being pooped out by a fish, they might have to penetrate a snail and then perhaps a clam before being eaten by another fish. Finding a parasitic worm in a giant squid could help scientists more fully understand where the worm journeys in its weird little life.

Bolstad also wanted to retrieve a tiny calcium carbonate bone called a statolith from within the squid's head that could hold a clue to the giant squid's lifespan—one of the many creature's many mysteries. "The squid has this little crystal floating around inside a fluid filled chamber," Bolstad said. "The motion of the crystals in there tells the squid about its motion and momentum and position." Squid statoliths function like our ear canals, helping the squid balance in the water. They also have growth rings, which could theoretically help estimate the age of the squid. But even though scientists can count the growth rings, they don't yet know how often they accumulate, Bolstad said.

But a giant squid statolith is about the third of a size of a grain of rice, making removal from a larger squid rather tricky. "It's very difficult to cut into a frozen giant squid head," Bolstad said. "You need it to be like in this sweet spot of partially defrosted but not too defrosted." The crystals always occur in a fluid-filled chamber in the same general region of the squid's head, so scientists have to take a scalpel to the area without crushing or breaking the fragile crystals. "It's a little bit of a lottery," she said, adding that she successfully scooped out one of the squid's two statoliths.

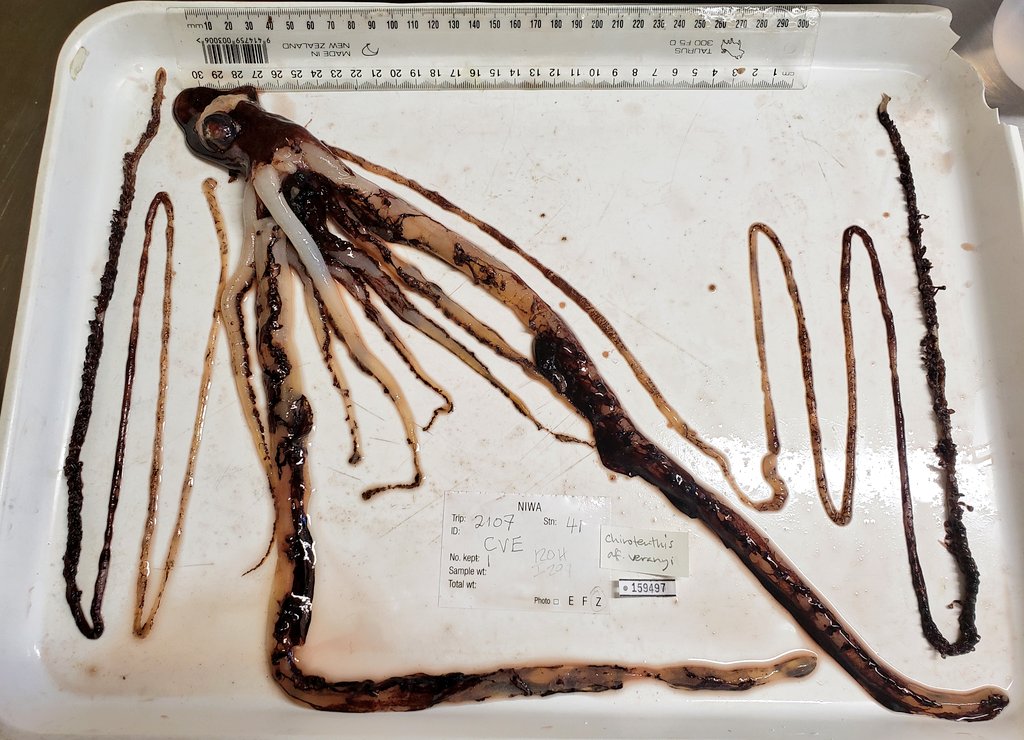

Although the squid cube was perhaps the grandest squid of the frozen bunch, Bolstad's lab thawed another significantly-sized squidsicle that turned out to be the head and arms of a truly big giant squid. Even though the partial specimen was missing the bulk of its body, the head and arms alone weighed more than the small giant squid.

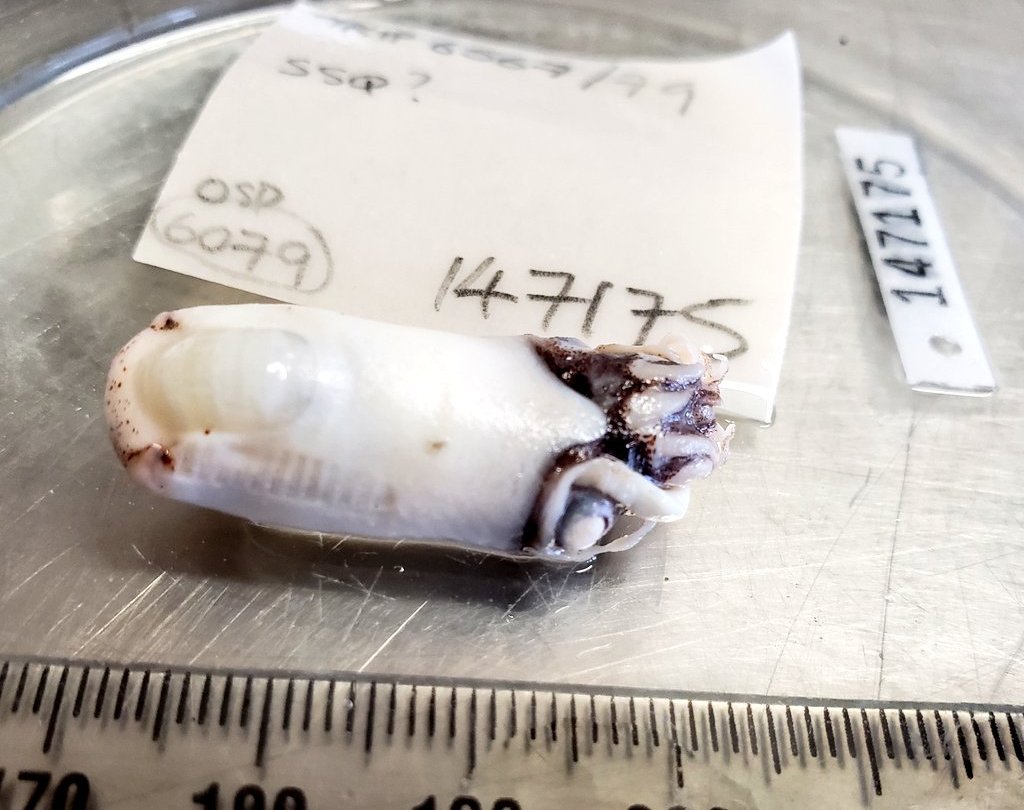

While Bolstad was in the lab, NIWA asked if she could identify a tiny specimen that was collected separately. The squid, which resembled an itty-bitty burrito, was the elusive and iconic ram's horn squid, Spirula spirula. The species gets its common name from a delicately whorled shell inside its body, which could be seen poking out from the mantle.

The past 15 years of squid unboxings have unearthed at least 30 species that have yet to be described and named, Bolstad said. [CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said 30 species had been found this year.] "It's the chance to potentially open a box and really make a discovery," she said. "To experience taking something out of a box that one or two people have seen before," she added.

Bolstad's lab preserved around 20 specimens to be held in the collections at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Her lab will return to Wellington next year or even sooner to do it all over again, unwrapping bags and unboxing cubes of small giant squids, giant giant squids, and many more squids of all sizes, observing all they can before the rot sets in.