Several years ago in the Yukon goldfields, within the traditional territory of the Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in, a miner named Diana Phillips came across a strange sort of nugget. Phillips initially did not know what to make of the mud-brown blob, which looked more or less like a rock, according to the Yukon News. But a closer look revealed the roundish nugget was covered in fur, revealing it was not mineral but animal in origin. It was a Fur Sphere, plucked from ancient soil trapped under permafrost for thousands of years.

Phillips and other miners working in the Yukon fields sometimes uncover the bones of Ice Age creatures, such as the teeth and skulls of mammoths and bears, Yukon government paleontologist Grant Zazula said on the gloriously Canadian radio segment "Northwind with Wanda McLeod." But the discovery of a mummified creature, replete with fur and skin, is a much rarer find than bones alone. Phillips sent a photo to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Center, a research facility and museum in Whitehorse, where researchers confirmed the Fur Sphere comprised the mummified remains of a 30,000-year-old arctic ground squirrel that lived and died in the Ice Age. A few distinguishing features protruded from the tiny mummy: a small hand, claws, ears, and a little tail.

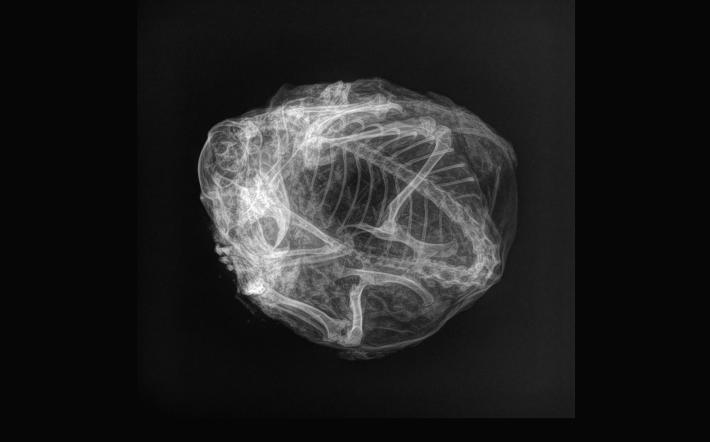

The researchers took the spherical squirrel to a veterinarian for an x-ray, which revealed the squirrel was curled up in a fetal position, giving the mummy its remarkable roundness. This position suggests it died while hibernating. And the ground squirrel's bones suggested it was quite young, likely less than a year old when it died (the squirrels generally live around eight to 10 years).

Unlike the certified big boys of the Ice Age, arctic ground squirrels are still around and seem to be doing quite well in their stomping grounds of Alaska, Canada, and Siberia. They spend seven to eight months of the year hibernating, during which time they adopt the lowest body temperature recorded in any mammal. A 1989 study from the University of Alaska Fairbanks found the internal body temperatures of hibernating arctic ground squirrels dropped to 26.78 degrees Fahrenheit—below freezing. Yet the squirrel's blood remained liquid, thanks to a phenomenon known as supercooling. Temperatures this cold make a wreck of the squirrels' brains, shrinking neurons and losing synapses. But the squirrels bounce back with the thaw of spring, able to sprout loads of new synapses within hours of being roused, Ferris Jabr reported for Scientific American.

The Fur Sphere will be displayed later this spring at the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Center for all to behold and ponder. But it is certainly not the first Fur Sphere to be found in the area. In 1981, a miner named Manfred Peschke was hosing down a stream bank in the goldfields when he noticed an egg-shaped thing drifting on the backwash. He'd found a Fur Sphere of his own: a ball of silt with some brownish fur sticking out. Peschke's egg was also an arctic ground squirrel, freeze-dried as it hibernated over 47,000 years ago. The specimen was nicknamed the "Moon-Egg" and you can see a photos and x-ray of it here.

Modern ground squirrels no longer live in the Yukon goldfields, as they cannot dig through the permafrost to dig their nests. But miners in the area frequently stumble upon Ice Age ground squirrel burrows and nests, as well as their ancient seed caches. My heart trembles just thinking about all the Fur Spheres studding the icy ground of the Yukon—out of sight, and yet to be discovered. O, ancient sleeping beauties, perfectly preserved by your eternal rest! O, preciously collected seed caches, never to be eaten! O, itty-bitty mummy, shuffled off this mortal coil before your time! Forget poems about the moon, I want poems about Fur Spheres and Moon-Eggs!