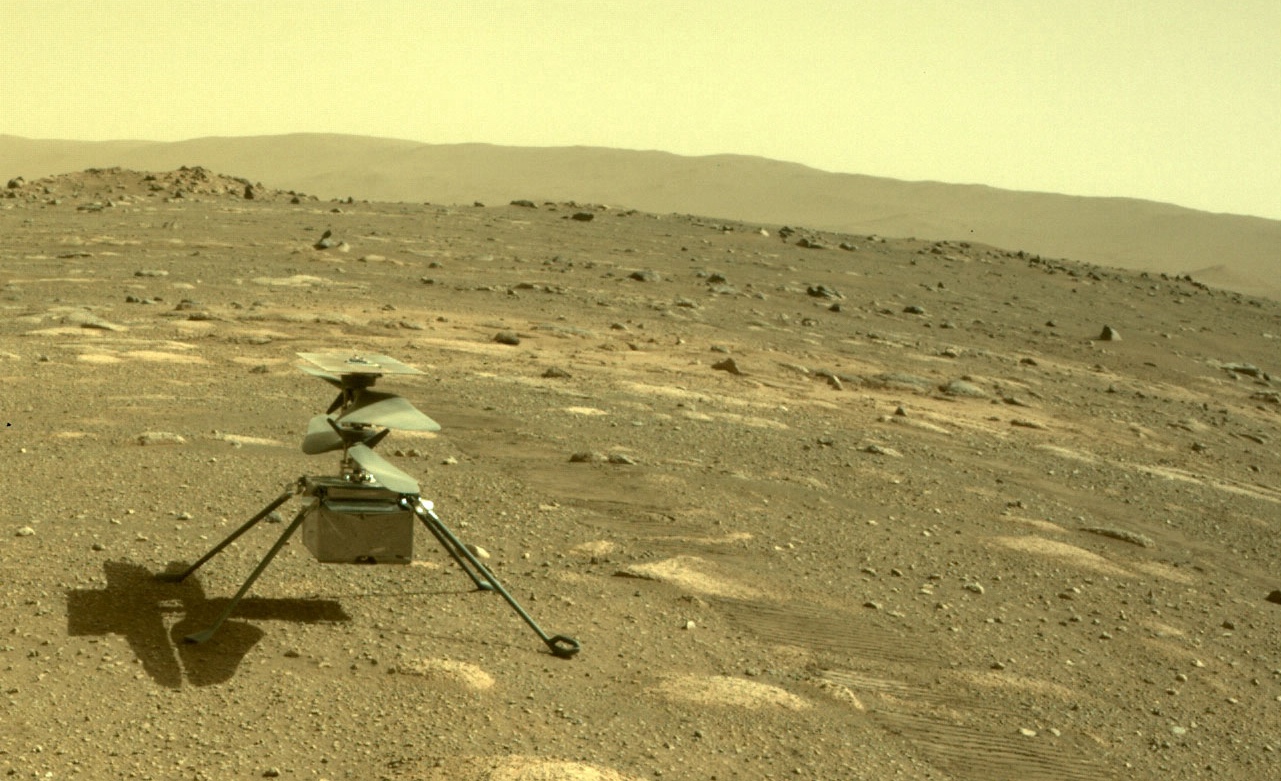

Ingenuity, the poky little helicopter puttering about the Martian skies, has flown its last. The craft suffered a hard landing during its Jan. 18 mission, damaging one of its rotor blades and permanently grounding it. This is no disappointment. Ginny, as its handlers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory nicknamed it, is a roaring, unqualified success. When it touched down with the Perseverance rover and took off on its own in April 2021—the first-ever powered extraterrestrial flight (as far as we know)—it was scheduled for just five flights. It made 72.

"She has blown out of the water any sort of metric of success," Theodore Tzanetos, JPL's Ingenuity team lead said upon the occasion of its 50th flight, and there really is no expectation the helicopter failed to outdo. It was supposed to be airborne for about five minutes across its missions; it stayed aloft for more than two total hours. It was supposed to cap out at 16 feet of altitude; it soared to 79 feet. It was only supposed to hover directly above and nearby its landing site; it ended up traveling 11 miles. It was only supposed to fly to prove it could; instead it ended up scouting interesting sites for Perseverance to travel to and cache material for future sample returns. Sometimes I think NASA intentionally undersells its expectations so that we can be proud of these overachieving little crafts—it sure works on me.

But Ingenuity couldn't fly forever. On flight No. 71, it was forced to make an emergency landing. Flight No. 72 was supposed to be a quick little jaunt to gain some altitude, look around, and determine exactly where the helicopter was. During its descent, the craft lost communication with Perseverance, which relays its signals to Earth. When contact was regained, it was clear that venerable old Ingenuity had touched down for the last time.

The end of an era.

— Paul Byrne (@ThePlanetaryGuy) January 25, 2024

The Mars Ingenuity helicopter sent back this image following the unexpected loss of communication during its 72nd *of five* planned flights on 18 January 2024.

One of its main rotor blades is damaged, and the helicopter will not fly again.#ThanksIngenuity pic.twitter.com/7qPg5seGN7

NASA still isn't really sure what went wrong—a postmortem will come—but that Ingenuity even flew in the first place is the more extraordinary finding. The helicopter's operation was purely theoretical: there is no place on Earth it could have been properly tested. On Earth, helicopters max out at about 25,000 feet. The air on Mars, however, is so thin, with so little for the blades to push against, that the Earthy equivalent would be operating at 80,000 feet.

This formed the greatest challenge for Ingenuity's designers, and their solution set a precedent that could have momentous implications for the future of extraterrestrial flight. The problem was mass. In air pressure that's just one-hundredth of Earth's, a Mars helicopter had to be as light as they could possibly make it. That meant no military-grade hardware, no cutting-edge technology, no luxuries like radiation shielding. Ingenuity's parts were, more or less, off the shelf. Its processor was a 2015 smartphone chip. Its rechargeable lithium batteries were the kind you buy at the store. In the end, Ingenuity weighed just four pounds. None of its components were guaranteed to survive the unpleasantries of the vacuum or the crazy temperature swings on the Martian surface, but now that we know commercially available parts can handle it, it opens up huge new possibilities for the next time we want to take off on another world.

Like Dragonfly. Scheduled to launch in 2028 and arrive at Titan in 2034, Dragonfly will spend more than three years zipping around the big, wet, Saturnian moon, sampling diverse and far-flung locations in order to learn more about the past, present, and future of life elsewhere in the solar system. Titan has a thick atmosphere, so the rotorcraft can be relatively robust—nuclear-powered and about the size of a car—but every gram matters. The lessons learned from Ingenuity will inform every extraterrestrial flight we ever make.

Let me confess to you that I have a problem: I can't help anthropomorphizing the little guys—the probes and rovers who do the hard work in space and on other planets. I get genuinely sad when I think about Voyager, coasting out into the great blackness, beeping its last beeps. I would do anything to help poor clumsy SLIM, who tipped over sideways on the moon and is sending back photographs of the ground. Did I tear up over the poetic translation of Opportunity's last data dump before it went dark forever? MAYBE. I recognize this tendency in me for what it is: childish and possibly kind of rude to all the smart and talented humans who actually conduct these missions. I'll try to be more rational. But I do have to say: NASA's not really helping when it puts out tearjerker promos like this one.

Flight 72. That’s the final flight for our Ingenuity #MarsHelicopter.

— NASA (@NASA) January 25, 2024

Ingenuity and its team proved that powered, controlled flight on another world was possible. #ThanksIngenuity. You may rest, but your legacy will continue to soar: https://t.co/uEe2ZAw2ML pic.twitter.com/9YlmWFpl2z