AUGUST TOWN, Jamaica — It's not simple to get to August Town, but it is easy. Anyone can take the road into this Kingston suburb, founded as a haven for freedmen. Its name refers to Emancipation Day of Aug. 1, 1838, which is celebrated as a national holiday. On the way in, one can see a beautifully preserved mural of two 20th-century men who capture the ethos of Caribbean black liberation: Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie. Selassie's legacy is more contentious—the Rastafari people who venerate the late Ethiopian emperor are not universally loved, even here—but there's little controversy about Garvey, whose likeness appears on the $20 coin.

At the time, I had no idea that Garvey would soon be pardoned by Joe Biden in one of his last acts as president, plastering Garvey's name in American headlines for the first time in decades. He was convicted on trumped-up mail fraud charges in 1923, a prosecution less about any crime than it was about Garvey's towering stature as an activist who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and advocated for black people's rights in the U.S., Jamaica, and around the world.

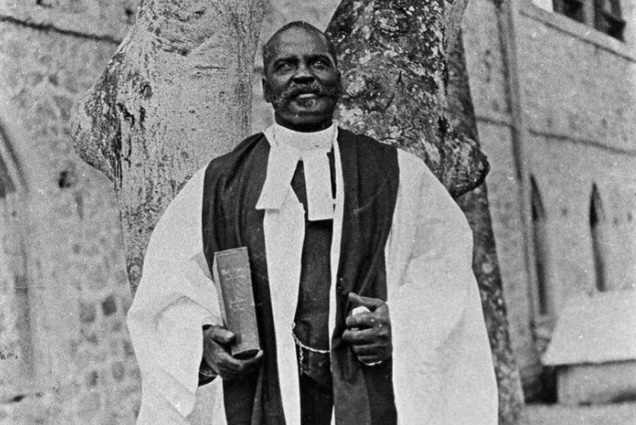

I'm not strictly here for Garvey, though ultimately I am. I'm on my way to see Alexander Bedward's church, or what remains of it. The congregation led by Bedward and largely inherited by Garvey is one of the West's most important liberation stories, one that doesn't make it into most history books. Jamaica's modern history is perhaps best understood through the schisms and revivals that motivated Bedward to start the Native Baptist Church in the late 19th century. Specifically, the people who would form the Native Baptists had grown quite distrustful of the mainline Baptists and their friendly relations with British and American missionaries. The Panama Canal and the railway projects were paying free black people a pittance compared to other laborers, and the people of August Town started to feel like maybe they'd gotten a bit of a raw deal. Bedward preached a radical anti-establishment message of self-sufficiency and pan-Africanism. This, unsurprisingly, got Bedward arrested for sedition and committed to a mental asylum.

Bedward lost some influence in his later life, but he told his congregation that he was only the first in a series of prophets—that he was the Aaron to Garvey's Moses. By the time he died in 1930, most Bedwardites had become Garveyites, and a few years later Rastafari permanently toppled the colonial hold on cultural hegemony. Bedward's influence still exists in Jamaica wherever racial consciousness does, but actual, physical relics of Bedwardism are hard to find.

"White man want to see Bedward Church," an older man says to another bystander dressed in basketball shorts. On the walk to the church, there are residents with concrete and cement pails filling in cracks on the street, or repairing tenement housing. They nod as we walk past, furrow their brows at the American. August Town has been a DIY community since its inception, and the people who live here quietly work on it each day.

Bedward's church, the Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church, completed in 1905, is now a collection of roofless walls behind chain-link fence, a faded historical tourism sign placed at the entrance. The fence is to keep vandals out. A man unlocks the fence for us and points to a tree about 20 feet away from the entrance. "That the tree there." This is the tree that Alexander Bedward climbed to await God's chariot to carry him away. The chariot never arrived, and the colonial newspaper played up the literalism of the act, and the Anglicans running the island threw him in the asylum. It was a political act: Bedward was not crazy, and had organized a labor strike that was preparing a massive demonstration in Kingston. The Anglican Church apparently felt as though this would be detrimental to its preferred status on the island and intervened.

Inside the church's walls is a remarkably calming silence—nothing aside from the susurrus of the breeze passing through the overgrown grass. The roof collapsed long ago and now the church is open to the pristine sky and the jade-green mountainside, as beautiful a sight as any you can find on the island. But it's evident that Bedward's Church is not a tourist attraction. For a white person, that's an easy distinction to determine: If the locals seem excited to see you, you might be in a tourist trap. If they seem confused about your presence, you're in the right place. Tourists don't even really go to Kingston, really; they go to Montego Bay. They sure as hell don't go to August Town.

Another local asks: "Want to meet the last living Bedwardite?"

"What?" I say, presuming I heard incorrectly.

"Yeah man," he says. "Still one left, you know. We take you up, see if he's home."

"I don't want to impose," I say, aware that I'm already stretching the bounds of hospitality. I've been escorted into August Town because one does not show up in August Town unannounced. My presence has been cleared with the Don of the neighborhood, and my escort—a broad-shouldered Rastafari PhD working with CARICOM on global reparations efforts—is there to keep an eye out, and to steer me right when I might go wrong. He leans in and reminds me that as a guest, if I refuse the offer it might come off as impolite.

Earlier in the day, my escort and I discussed Garvey, and the American slander of his legacy that still hangs over Americo-Jamaican relations. In the years since his death, many narratives emerged to explain "why" the United States government targeted and took down Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association. The narratives are complex, perhaps because the obvious reason feels too obvious: Garvey was building wealth in places that the American government couldn't tax, and putting that money into the hands of people who wanted to smash its hierarchies. The rest is detail. But Garvey was not an uncomplicated figure.

"Isn't it a little arrogant, I guess," I say, choosing my words carefully. "Given that Rastafari and Caribbean liberation is about rejecting hierarchy … how does that work with Garvey declaring himself the President of all of Africa?"

"Sometimes it takes a man of supreme confidence," my escort says, his voice rising to the same impassioned tone I heard when I accidentally slammed his car door (you don't do that in Jamaica; loud noises put people on edge). "Marcus Garvey was that man. He showed Africans that losing dignity was a choice."

The legacy of Garveyism is complex. Even as a term, "Garveyism" is an academic taxonomy cooked up in those Western-style universities that "Garveyists" often consider biased against blackness. Much as I'd hate to contribute to anti-intellectual discourse, those who reject the term have a point: Many of Garvey's followers were Bedwardites who had lost their flock leader, and many of those Bedwardites were simply Baptists looking for a church that recognized that the black experience in the world is a unique one. In textbooks that deploy the "Great Man Theory of History" theory, Marcus Garvey is a lone wolf. In Jamaica, he is a martyr in a faith tradition that carries many names.

The chasm between the best and worst of Garvey's philosophy is deeply felt in August Town, where one can find context for aspects of the philosophy that overlap with libertarian "sovereign citizen" nonsense, antisemitic tropes, and black supremacist teachings in extremist fringes. The remnants of Anglo-Israelism are apparent in the Caribbean—I noted an otherwise unremarkable liquor store called Black Jew Liquors, which might not fly in America—and Alexander Bedward was dangerous because he had unlocked a theological loophole in the metaphor of scripture: The black people of Jamaica were the Israelites, and the white colonialists were the Pharisees and the Sadducees. But these men were and still are largely Christian with a dash of esoteric Abrahamic iconography. Unlike similar groups in the United States, there is minimal interest in understanding if black people are the "real Jews," because casting August Town as Zion was always understood as a metaphor.

The (alleged, but also not exactly secret) Don of August Town is a reggae artist named Sizzla Kalonji, whose very public bigotry against queer people (and subsequent sanctions on radio play and performances) dominates news about the artist. The majority of Sizzla's time is not spent on bigotry. It is spent administering a fortified oasis known as Judgment Yard, also home to a Rastafari tabernacle for the Twelve Tribes of Israel (no relation with American Black Hebrew Israelites). When I visit, children are laughing and splashing in a watering hole created by a collapsed roadway. Sizzla's mother even lets us peek into the recording studio. I think it's important to clarify that August Town is not dangerous in the way Americans often picture. It's quiet and peaceful, and aside from petty crime and scattered fights between drug addicts, most of the violence occurs when the military decides it's time for a raid.

While Sizzla's bigotry is what grabs headlines, his respect within the community is derived from his militant refusal to engage with Western culture. In fact, Sizzla Kalonji still refers to himself as a sanctified Maroon Priest who has legal authority passed down by King Cudjoe. (Maroons were escaped slaves and their descendants, who battled the British during the colonial era. Cudjoe was a Maroon leader during the First Maroon War of 1730.) While this may sound like fantasy, the British did indeed sign a treaty recognizing the Maroons as an independent nation in the 18th century after getting shellacked in the war. That treaty would be torn up after the British victory in the Second Maroon War in 1796.

A deep distrust of white powers is the appropriate framework in which to place the rise of Alexander Bedward, Marcus Garvey, and, yes, Sizzla too. Jamaica has long been a Ponzi scheme for Western governments, and Garvey recognized that anything that generates money for the Ponzi scheme was inherently bad for black Jamaicans. Every victory of the abolitionist effort was met with violent retribution and broken treaties. August Town and Bedwardism came into existence because the British had cooked up a scheme to cut free black people out of the workforce.

"Let's see if he in there," one of my companions says as we reach the top of an unmarked street. Compared to the tenement housing construction in most of August Town, the rows of houses here are notable for looking like they would slot in perfectly in small-town America. The dreadlocked man shouts at the house, letting the resident know there are visitors. A feeble bald man with brown skin emerges from the front of his house smiling, then sees me and visibly recoils. I am not at a tourist attraction.

"Man come to see Bedward Church," my companion explains. "We want to bring him round meet you. OK?" The man nods and his grimace rotates to an amused smirk.

"Man know I never met Bedward?" the bald man rasps. I nod. It's been explained to me that Bedward died before this man's family relocated to August Town, and he is simply the last living person to have stood in a Native Baptist pew. "And man still want meet me?" I nod again.

"Maybe you want a picture with him?" my companion says. I remember my escort's advice about being a guest, so I'm able to restrain myself from blurting out, Please don't ask that, oh my God, I was not going to ask this man for a picture. The last living Bedwardite politely shakes his head to indicate he'd rather not. I let out the breath I was holding, and then I stop myself from a performative attempt to tell the man the same lie I like to tell myself, the one about not being just another ignorant American. I think he senses my embarrassment at the situation and softens, telling me I am welcome to ask him a question. I try to think of the smartest thing I can ask, but instead settle for the simplest: I ask him what, if anything, he remembers about being a Bedwardite.

"We didn't think of ourselves as Bedwardites," he tells me. "I'm a Christian. But we knew what the man want for all of us."