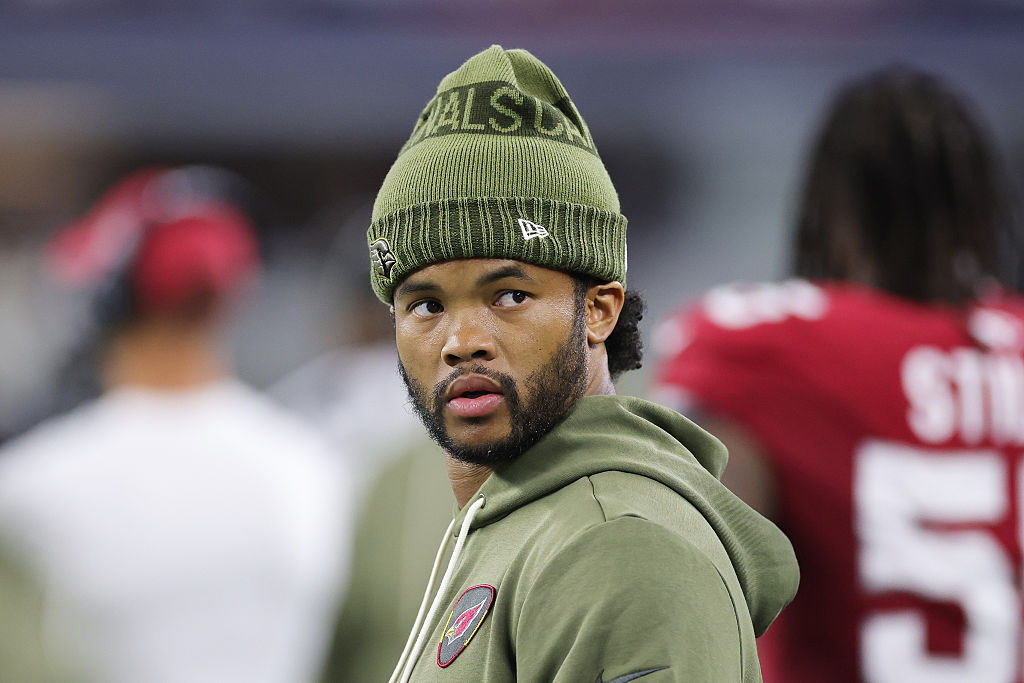

The scientists in the MLB laboratories are always concocting new ways to avoid paying player salaries, and the San Francisco Giants' front office is no exception. Utilityman J.D. Davis, who played 144 games for the Giants last season, was released by the Giants on Monday, roughly a week after they signed free agent Matt Chapman on March 3. Davis, who had won his arbitration hearing in February and earned a salary of $6.9 million (the Giants' offer was $6.55 million) is now only owed 30 days of termination pay, which works out to about $1.1 million.

While the current collective bargaining agreement guarantees one-year contracts for arbitration-eligible players if they are negotiated with the team, this guarantee does not apply for salaries determined through an arbitration hearing, as Davis's was. What's in question is not whether the Giants are allowed to release Davis while only owing him termination pay—they explicitly are, even if "The rules let us!" is a defense that does not hold up in the court of public opinion—but whether they negotiated in good faith to avoid going to arbitration.

Per The Athletic's Andrew Baggarly, who spoke with Davis's agent Matt Hannaford, the Giants made one offer to Davis an hour before the deadline to exchange salary figures for arbitration. The offer was, in Hannaford's words, "hundreds of thousands" less than what the Giants filed for. President of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi said that the Giants offered $6.4 million and received an unofficial counteroffer around $7 million from Davis's agent only 10 minutes before the deadline. Not to project my own emailing anxieties upon a professional athlete's agent, but Zaidi's claims don't contradict Hannaford's. It's logical that a text message sent by GM Pete Putila one hour before a deadline would result in a similarly last-minute counteroffer. Because the Giants, like most Major League teams, do not negotiate after the exchange deadline, Davis went to arbitration, where he won but at the cost of a guaranteed salary.

As Baggarly noted in his article, teams have released arbitration-eligible players prior to Opening Day before, but it hasn't occurred to a player with as much money on the line as Davis, which means this cheap tactic falls under the categorization of "precedented but notable." The harshest part, after the part where Davis lost out on millions of dollars, is the timing. With a little over two weeks before Opening Day, the Giants avoid an additional 15 days of termination pay, and Davis is now a free agent at a time when most teams only sign players because of an injury to someone else.

Davis will have to find a spot in what has been an excruciatingly prolonged free-agency period. Starting pitchers and Scott Boras clients Blake Snell and Jordan Montgomery are still unsigned. If the Giants had signed Chapman to his three-year, $54 million contract sooner, they could have traded Davis or placed him on waivers at a time when teams were more seriously looking for options.

But this is not to pin Davis's current situation on Boras or Chapman; the front office made this call. If the Giants planned to test the third-baseman market, they could've moved Davis anyway. Instead they turned him into a backup plan: If Chapman didn't sign, they would have Davis. If Chapman signed, they could cut Davis and be glad to pay $1.1 million for the ease of mind he provided. In either world, the fact that Davis's contract went to arbitration meant that Giants were in a win-win situation: $450,000 is a rounding error for a team, but the $5.8 million they save by cutting him is not. The only obstacle would be whether Zaidi and his front office could stomach it. Clearly they were more than capable.