PORTLAND, ORE. — Global capitalism begins with apparel. Slaves were brought to the American South from West Africa to do farm labor, and by the 19th century that largely meant cotton, a ubiquitous puffball that is easy to grow and aggravating to harvest. Seeds would be removed with a cotton gin, and the bulk of the puff would be sent to England, where it was turned into thread by gigantic steam-powered looms, woven together, and sewed into mass-produced coats, shirts, and pants that were sold in retail shops all over the world.

In the 1970s or thereabouts, this process broke in two: The corporation, which once lorded over vertically integrated processes to create a final product to sell to consumers, became a contractor coordinating logistics between an omniplex of factories dotted all over the world. In the post-industrial world, which is primarily in the Global North, brands deal with marketing, design, logistics, and materials acquisition; that workforce operates out of air-conditioned offices. The more recently industrialized countries of the Global South, where labor is cheaper, less inclined, or just less able to unionize, and where governments are eager to play ball, is home to a constellation of separate factories, each operating as independent contractors and competing with each other in a never-ending race for lower prices and more innovative material science.

Nike, Adidas, New Balance, Under Armour: These companies do not actually spin thread, tan leather, vulcanize rubber, or even put together the shoe. They design prototypes of a product and then facilitate all the actions necessary to make money off it. They pressure supplies and manufacturers at every level of the manufacturing process, send the product all over the world, sell it at a markup. The people in the brand offices coordinate that labor; the people in those factories actually do it. This is globalization, and it encompasses every transaction in the world economy.

To walk the floor at The Materials Show, an industry event that goes down four times a year—there’s two in Portland, home of Nike, Adidas of America, and several other major activewear concerns, and another pair in Boston, the home of New Balance—is to see that grand abstraction made flesh. In the aisles, a parade of designers, materials acquisition people, and executives clad in Activewear Professional go from booth to booth, look at threads and rubbers and leathers, chat with vendors, and take little notes. “The show is about sourcing raw materials, mostly for the footwear industry,” Hisham Muhareb, the founder and owner of The Materials Show, tells me. “Nike, Adidas, Columbia, Reebok, New Balance—their product teams come here and they meet new vendors, meet their old vendors, talk about materials, components, and process.”

So you can see why I needed to be there. What I saw, mostly, were tables behind which vendors were sitting with swatches of cloth or treated leather, reams of thread, shoe soles, brochures, insoles. I will classify these vendors into three types.

The first type is public-facing companies peddling specialized solutions. Hewlett-Packard is here with 3D-printed shoe soles, trying to sell industrial printers and really get the latticing revolution going. Vibram, who make specialized soles for hiking shoes and those upsetting shoes with articulated toes, also have a booth. This is the smallest cohort at the show, and their vibes are based more in incremental technology solutions than “We are prepared to sell you more leather than one person could possibly imagine.” These companies are looking to sell brands on the technology that will populate these factories in the near future, so that they can, in turn, tell the factories they employ to get cracking on adoption.

The second is eccentric specialists, peddling niche solutions for niche products. One company sells materials made in the good ol’ U-S-of-A to both military contractors and New Balance, which markets a line of American-made products. One company I encountered was Reltex, a French company selling all natural rubber soles, made with a process they call Lactae Hevea, which involves extracting raw rubber from a tree and letting it sit in a mold for a week before forming it into a soft, comfortable sole. That process takes entirely too long to be scalable, but it’s great for boutique products.

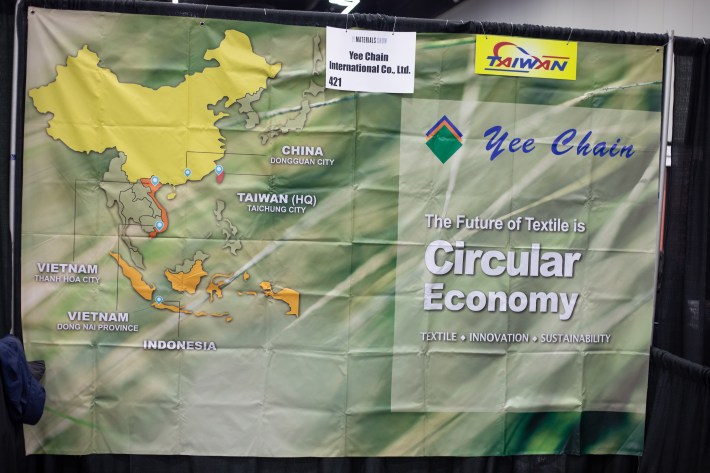

The third, which enfolds the vast majority of exhibitors, is overseas factories, primarily located in southeast Asia. They buy raw cowhides, many of which are from America, where we have a robust beef industry based on factory farming that prefers to keep cows indoors, away from mosquitos that could damage their hides; brands also prefer to avoid hides from Brazil, the world leader in beef production, on account of deforestation concerns. They also buy leather tanning chemicals, petroleum, chemical solvents, cellulose-based feedstocks, cotton, and a whole universe of other raw materials that they turn into swaths of fabric, shoe soles, inserts, thread, shoelaces, and the other building blocks for complete shoes. There are also the leather tanneries, thread manufacturers, polyester and spandex concerns, rubber vulcanizers, and insole pressers that form the backbone of the activewear industry. They have un-showy names: Shinta Woo Sung Textile Company, Tong Hong Tannery, Bu Kwang Textile, Nova Polytec Composites Co., things of that nature.

Those concerns are represented by hundreds of agents, all clad in business casual activewear. Many of them are Southeast Asians who speak solid but accented English; some are Americans, former brand employees who have leveraged their connections in the industry to move over to the materials side. Some trends in materials are apparent even at a brief glance. The big one is a move away from China and into Indonesia, Vietnam, and India. Some of that is a reflection of how China, with the help of Apple and other major tech companies, has climbed up the industrial curve and moved more of their production power to electronics and heavy machinery manufacturing. Companies would also rather their contracted factories be closer to each other to reduce logistics costs. Some of it is just a matter of geopolitics, and the United States’ dumb new economic cold war. But really, it's just that the vast majority of shoe assembling is now taking place in non-China countries, and local materials make the logistics of manufacturing more efficient.

Speaking of protectionist gambits: The Materials Show I attended was held in February, before the U.S. executive branch started to yank tariff rates around out of either some deranged dealmaking impulse or in an oafish attempt to game the markets. It was clear that it was going to happen, and that it was going to be bad, but it had not happened yet. The main impression I got from people who work for overseas materials factories, after asking around, was that they were not really scared of an American protectionist regime. Ronda de Bie, a Senior VP of Sales at ISA Next-Gen Materials, a consortium of tanneries with facilities in China, Vietnam, and America, told me that tariffs worried her “a little.” It was complicated, or at least annoying, she allowed, but the way in which it would play out was plain enough.

“From a supplier standpoint, we’re not the one exporting anything,” de Bie said. “It’s the brands who have to deal with that. But most brands are coming back to their supply chain and asking for help or relief with their supply chain. They want us to pay for it so they don’t have to.”

But those brands will have to pay, because factories do not grow overnight. Cargill, a sprawling agribusiness concern that holds the distinction of being America’s largest privately held corporation, recently constructed a facility in Iowa to manufacture 1,4-Butanediol, a common solvent in the clothing industry, smack in the middle of 95 million acres of corn agriculture. It was the only logistically rational place to put a factory serving that purpose. That factory took five years to build. Even setting aside the wild instability of how the Trump administration has employed their tariffs, the U.S. doesn’t really have a non-defense industrial policy to speak of. It also does not have the technology that those foreign factories employ, or a population that really wants to work in clothing factories. America would have needed to make a lot of drastically different decisions over the last five or so decades for that to be the case: higher immigration quotas, different trade deals, consistent investment in new industrial technology. We instead opted to become the front office for Capital. This is the price of being management.

What united all three of our vendor subtypes at The Materials Show was a focus on sustainability, a word that can mean a lot of different things. For many people reading this, the only path to a sustainable future is wholesale regreening, the centrally planned replacement of the productive economy as history has made it with a new economy driven by electricity that produces marginal greenhouse gases, cattle pastureland rewilded by carbon-devouring forests, and an agricultural economy based primarily on feeding the entire planet.

That's not what Nike wants, of course. But it does want something different from the way it's always done business. A true cynic will immediately think “a marketing opportunity,” which is not entirely invalid, but also too narrow. After all, this event was an industry show; the people there were marketing sustainability not to consumers, but to corporations. Aside from myself, there was no consumer-facing entity there, just people making purchasing decisions on which tanneries will work for Nike or Adidas.

Brands are willing to go easier on Mother Earth, provided that doing so contributes to the continued function of their business. The materials people are there to let them know that those goals are reachable, provided those corporations choose the best and most cost-effective corn-based what-have-you. Everyone is there to do business, but those concerns are less nihilistic than the politics that enfold them, precisely because they are less ideological.

The ways in which manufacturing practices can be more sustainable are endless and evolving all the time, but there are four broad gestures that companies pursue. You're probably familiar with greenhouse gas reduction. Brands set goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and then pressure their suppliers to adopt technologies and methods to achieve or just convincingly feint at achieving these goals. They audit their supply chains with the help of consultants, then present the results as proof that they are decarbonizing their operation, and therefore do not deserve the ire of government regulators or ecoterrorists.

Deep in the show, Kira Jones stands behind a table that holds a small bowl of inedible dent corn, pamphlets, and several small foam corn cobs. Kira is here on behalf of Qore, a joint venture between Cargill and HELM, a brand marketing and logistics company. She’s selling Qira, the brand name for a new bio-based form of 1,4-Butanediol (BDO in common parlance), a ubiquitous chemical solvent used in the manufacture of spandex and other synthetic fibers (and also electric car batteries, a growth market). BDO is usually synthesized from acetylene, commonly manufactured by partially combusting methane residue produced during oil refining; that process unleashes a remarkable quantity of greenhouse gases. Qore provides a less taxing alternative that also doesn’t depend on a finite resource.

“Corn is our raw material,” Jones said. “It’s what we use as our feedstock.” Feedstock, in this case, means anything that gets fed into an industrial process to make something else. “62 percent of this corn kernel is starch. Cargill owns a bio-refinery, and they take an outrageous amount of corn on a daily basis and they fractionate it into its different components, then they basically pipeline the dextrose to our facility adjacent to the bio-refinery in Iowa, right in the center of the corn belt. Almost all of our corn is sourced from [within] a hundred-mile radius of our plants.”

What part of a shoe does this go in? “Almost any part of a shoe." This is part of the sales pitch, but it happens to be true: There’s a shocking quantity of polyester in mass-market sneakers. It’s in shiny laces, air pockets, waterproof coatings, spandex, shoe soles, fibers themselves. “We are using a resource that is in abundant supply, that is annually renewable, with a lower carbon footprint than our other traditional production methods of 1,4-Butanediol,” Jones said. “With our low product carbon footprint, which we’ve had done by a third party, LCA Company, we can provide transparency all the way through. A lot of brands are really big on greenhushing or greenwashing, [but] a lot of them want to make sure it’s legitimate. We offer that.”

Imagine that you are a buyer at a sneaker brand, looking to reduce your end-of-line greenhouse gas totals. There is no silver bullet that will let you do that, so you’re seeking little edges, one after another, to get those numbers down in the end product. You see our friends from Cargill, a reliable brand famous for its agribusiness solutions, selling a necessary solvent at a reduced carbon cost. You will then approach your vendors, and suggest that they buy BDO from these guys, so that you can mark a reduction in your total greenhouse gases, getting everyone—you, and the vendors that make your job possible—closer to their climate goals.

This applies to every aspect of production. What kind of electricity does your factory run on? How efficiently can we situate the various factories making the various parts of a shoe to reduce transportation costs without shoring our manufacturing process in a consumer-forward country, where we would be subject to the various minimum wage laws we’re avoiding? How can you make sure you’re not overproducing? The list is endless. There is no ideology in any of it, merely the ever more precise tuning of a human-powered machine that spans the globe.

But even if your business is using BDO at a reduced greenhouse gas cost, you’re still using it as a solvent in the manufacture of petroleum-based clothing materials. The global fashion industry produced 71 million tons of polyester in 2023, and petroleum-based materials don’t decompose the way that organic materials like cotton or leather do. They also shed microplastics at an extraordinary rate, especially in washing machines. As more and more people come to see plastic as a tumor that humanity has inflicted upon the Earth, the clothing industry is faced with the question of what they’re going to do about it. Recycling plastic was global capitalism’s first proposed solution to this quandary, one the clothing industry still pursues to this day, even as it has come to seem more and more out of step with the needs of genuine sustainable production.

“The biggest challenge facing sneakers and recycling is that there are so many component pieces in every sneaker that it’s almost impossible to pull it apart and recycle it,” said Elizabeth Semmelhack, the director and senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto. The activewear industry has sought to make plastic products made from a single material to make for easier recycling. “Something like a Croc, or a shoe that’s completely 3D-printed, in concept, if you use a recyclable or sustainable material, that’s so much easier to recycle.”

Anika Kozlowski, an Assistant Professor of Design Studies at the University of Wisconsin, pointed out some of the problems with single-material recyclable shoes as a solution. “Any of these recycling technologies that come up, they require infrastructure to support the collection and the sorting that we don’t have,” she told me. “So even when Adidas put forward that Loop shoe, [which] was supposed to be fully recyclable because it just used one material, when Adidas sent it out to runners, they had a hard time giving these shoes back. Also, because the shoe was white, when they went to recycle this material, it came out as a beige. And still, because it’s a plastic base, there’s only so much that you can recycle it. It’s always going to downgrade each time, and it’s still going to require virgin input.”

This is the fundamental problem with materials science as liberatory framework: There’s always something. A fully recyclable shoe will still shed microplastics; leather, an incredible material that breathes well and lasts forever, still requires the maintenance of cattle monoculture, whose environmental impacts are well known; that product might still require plastic for true waterproofing. Waterless dyes use too much energy. Cotton is hard on soil. “No one is perfectly sustainable,” Kozlowski told me. “No matter what, even if you’re using the best of everything, you're going to have an impact.”

So what would actually work for large brands, I ask. Kozlowski answered with a brief “oof.” Her response cut against the core theses of globalized clothing production: “Actually trying to reduce how much you’re producing.”

“We make 20 billion pairs of shoes a year,” Semmelhack said. “Enough for three new pairs of shoes for every person on the planet. That’s too many shoes to get rid of.”

At the moment, the Bata Shoe Museum is presenting an exhibit on cowboy boots. Unlike the products of the sneaker omniplex, cowboy boots are generally made in small operations, from natural materials that eventually biodegrade. They require a commitment, as they conform to the foot of the wearer over time; a pair can last for decades with proper care. They are made from leather, a product of notoriously dirty cow agriculture, yes, but that filth is offset by their durability, and how long they tend to remain in use.

Durability does come up here and there on the floor at The Materials Show. I saw some allusions to leather’s potency as a sneaker material, and heard a Vibram employee insisting that their specialized hiking shoe soles were sustainable, actually, on account of their toughness in the face of repeated wear. But think about it from the perspective of everyone else who was there in their capacity as sneaker manufacturers: A consumer who successfully relies on two pairs of shoes per decade isn’t doing the global shoe industry much good.

Fashion is built on yearly cycles, the perpetual renewal of identity through consumption. Nike has a longstanding bugaboo about referring to itself as a fashion brand; the company much prefers instead to tell everyone that it is primarily concerned with athlete performance. The primary reason it sells new products year after year—or so it says—is not style or aesthetics, but because it's just making lighter and lighter running shoes year after year into eternity, the better to aid the improvement of the world’s runners. One guy I spoke to tried to sell me on a personal vision of Nike as a wellness concern instead of a fashion brand; it was a vision he felt the company had betrayed. It must be wonderful to have so much money and market share that you can lie to yourself about where it all came from, and where it all goes.

A public company, no matter how well intentioned or committed to sustainability it might be, will by its nature never commit to selling less. The clothing capital business is a beast that demands to be fed; the quest of materials science is to feed it something better or healthier than what it would ordinarily eat, which is more or less whatever is in front of it. That could be something that generates less in the way of greenhouse gases, or that doesn’t choke our oceans and our bodies with microplastics. It could also just be oil.

“I wonder if embracing built-in obsolescence for the sake of the planet could be something that we could do,” said Semmelheck, whose work is intimately concerned with the future of sneaker materials. In Future Now, Bata’s exhibit about what materials science will bring to the sneaker industry in the future, she describes the utopian state of material science: a fashionable sneaker made from biodegradables, mushroom leather, cotton, corn derivatives and the like, with a built-in expiration date and an understanding that, upon point of purchase, you will be chucking it into a compost pile next year, where it will do no harm and return to the earth in due course. Keep the fashion cycle, abandon the oceans full of garbage.

“Big companies tend to focus their sustainable practices on technological efficiencies,” Kozlowski said. “Things that they can do where they see immediate benefits and can communicate those benefits. Because marketing is so important, and sustainability—any sort of new, sexy, technological innovation, anything they can talk about—supports their growth. Because at the end of the day, that’s still what they’re intending to do.”

If that feels airy or abstract, the broader challenge is much less so. In the face of the emerging plastic apocalypse, there are just two true solutions: a scientific breakthrough in compostable materials so dramatic that it makes polyester outmoded, or a change in consumption so dramatic that people begin to wear the same two pairs of shoes every day for a decade. The activewear industry would naturally prefer the former.

The Materials Show unfolded in February 2025, during the first wave of DOGE horseshit that inaugurated the second and far more terrible Trump administration. At that moment, it felt as if the people wielding the levers of power didn’t really care about sustainability anymore, and were in fact more invested in its absolute opposite. In the months since, as the administration made one move after another aimed at repudiating consensus scientific reality, this disconnect only widened. At the highest levels, the U.S. was looking at these sorts of prosaic business miracles, processes that would make big companies more money and benefit the environment as well, and giving them a terse “No thanks.” It already felt antique—all of these global materials manufacturers, promoting sustainable practices to brand-side representatives at an internal industry event? Were we still doing that?

Jones, and other people I spoke to at the show, said that this was the right thing to do—“It’s our planet, we only have one”—and at some level I think this is something they really believed. Capitalism turns us into something we might not be otherwise, and this is a bad moment, but there are enough social and moral forces in our lives to keep (some of) us from actively cheering the annihilation of the planet, at least as individuals. I do think that the people at the show believed their sustainability work is helpful, and would prefer to pursue it over other solutions to the problem of sustaining the sneaker industry at large for laudable reasons. Still, that was not a sufficient answer for me; a person can be moral, but a corporation rarely is.

In my estimation, the first and most urgent reason for the industry’s ongoing emphasis on sustainability is still the need to market to eco-conscious young people. A close second, even as American politics turns towards defiance and nihilism and self-harm, is the specter of government regulation. An American, who lives in a country where wholesale governmental looting is a matter of daily reality and where the most idiotic excesses are pounded into your eye sockets in every waking moment, might be surprised by this.

“I think regardless of the culture of the time, the trends that we see, elected officials we see in power, the macro trend is that we all want to reduce our carbon footprint,” said Ryan Zakszeski, a senior business development engineer at Arkema, a French chemical company at the show selling high-performance foam for athletic shoes. “We all understand, as businesses, that it’s the future. The brands we work with are all pressuring us to reach their 2030 climate goals. If you don’t get going on your sustainability journey, you’re going to be dead in five or ten years from now.”

To the extent that its actions can be parsed at all, the U.S. government is currently working against this apparent future. But when you make stuff to sell—mountains of stuff, so much stuff that the human mind cannot fathom the volume of it—you cannot pretend that your industry will just function as it has forever. Sneaker manufacturing isn’t like tech, where you can blabber on about how you actually need to devour cities' worth of energy for years at a time in order to make Generative AI and keep your investors happy. These companies are in a more tactile business. Whatever Nike’s vision of itself might be, it sells shoes and facilitates the manufacturing of shoes. For a company in that business, thinking five years ahead means thinking about what the marketplace will be like five years deeper into multiple environmental catastrophes. A rational imagining of that world to come, or just one that’s reasonably hedged in deference to reality, would show them a world in which they are no longer permitted quite as much leeway.

I would hope that this sentiment does not give you too much optimism about the future of U.S. regulations. Our Congress is broken, lazy, obstinate, and compromised, quite possibly the most ineffective governmental institution in the developed world. But sooner or later, actuarially speaking, even they will have to reckon with the reality on the ground. Even if they don’t, and the tantrum of this moment somehow continues to unspool over a few chaotic generations, global companies are still compelled to work in global markets, and global markets include people who don’t live in gutter states that feed on their own futures. Those people would prefer a rational operating future from the apparel industry; those people will continue to need and wear shoes.

Dan DeHaven worked at Nike for 30 years before he hung his own shingle as a footwear design consultant at Shoe Dog Studio in Portland. Right now, he's working on cellulose-based material development for footwear, materials that can decompose instead of lolling in a landfill forever. “Look at what’s going on in Europe,” he told me. “If you don’t have a take-back program, electronics, cars have to be taken back, everything is moving towards if you make it as a manufacturer, you have to be responsible for its end of life.”

Jennifer Nolfi, the Director of the Sports Product Management Program at the University of Oregon, sees the industry’s sustainability push as a quest for survival. “I think that there’s a lot of people trying to figure out what they can do to prevent a negative impact on the industry," she said. "I think that no one has one answer, so there’s these little innovations that are happening to help reduce the impact. But I think it’s going to take us a while before we figure out how to totally make a product that is a closed loop. We have a long way to go. Anyone will tell you, the best answer for the planet is no product. But that’s not what anyone wants. It’s about finding a balance.”

This sustainability stuff isn't solely a cynical marketing gambit or an earnest quest for true environmental enlightenment. It’s a fight for survival being fought by some very hungry and fundamentally amoral entities with survival hardwired into their design. Everyone knows this can’t go on forever; the market insists that it must. A hack or a grifter can convince voters that the future will never come. A shoe company, subject to analysis with an understanding of what the future will look like, doesn't have that luxury.