Throughout the first season of The Chair Company, the protagonist Ron Trosper (Tim Robinson) goes to many places that he should not. He chases unsettling men and curious leads through parking lots, dingy apartment buildings, hoarder houses, government records offices, strip-mall eateries, precarious dive bars, and derelict business parks. But none of that compares to the thrill of seeing where he went in the very first episode: the site footer.

“A <footer> typically contains information about the author of the section, copyright data or links to related documents,” is how the Mozilla Developer Network describes a footer HTML element. Wikipedia’s current stub of an article on the web standard notes that “common items that are included or linked to from footers are copyright, sitemaps, privacy policies, terms of use, contact details and directions.” You know, the stuff nobody ever reads. It also notes that “infinite scrolling cannot be used in combination with footers, because the footer becomes inaccessible,” which implies that the footer is, in some respects, antiquated.

Any time I have ended up scouring a site footer, it is because something has gone very wrong. Well, not really, but it is because I have exhausted every other option. Search indexes have turned up nothing, social networks are similarly blank, the website’s most prominent sections in the top navigation lack the info I need. And so as a last resort, I start going through the sitemap in the footer. It is a hierarchical directory of all parts of a website, including the stuff nobody cares about but lawyers demand.

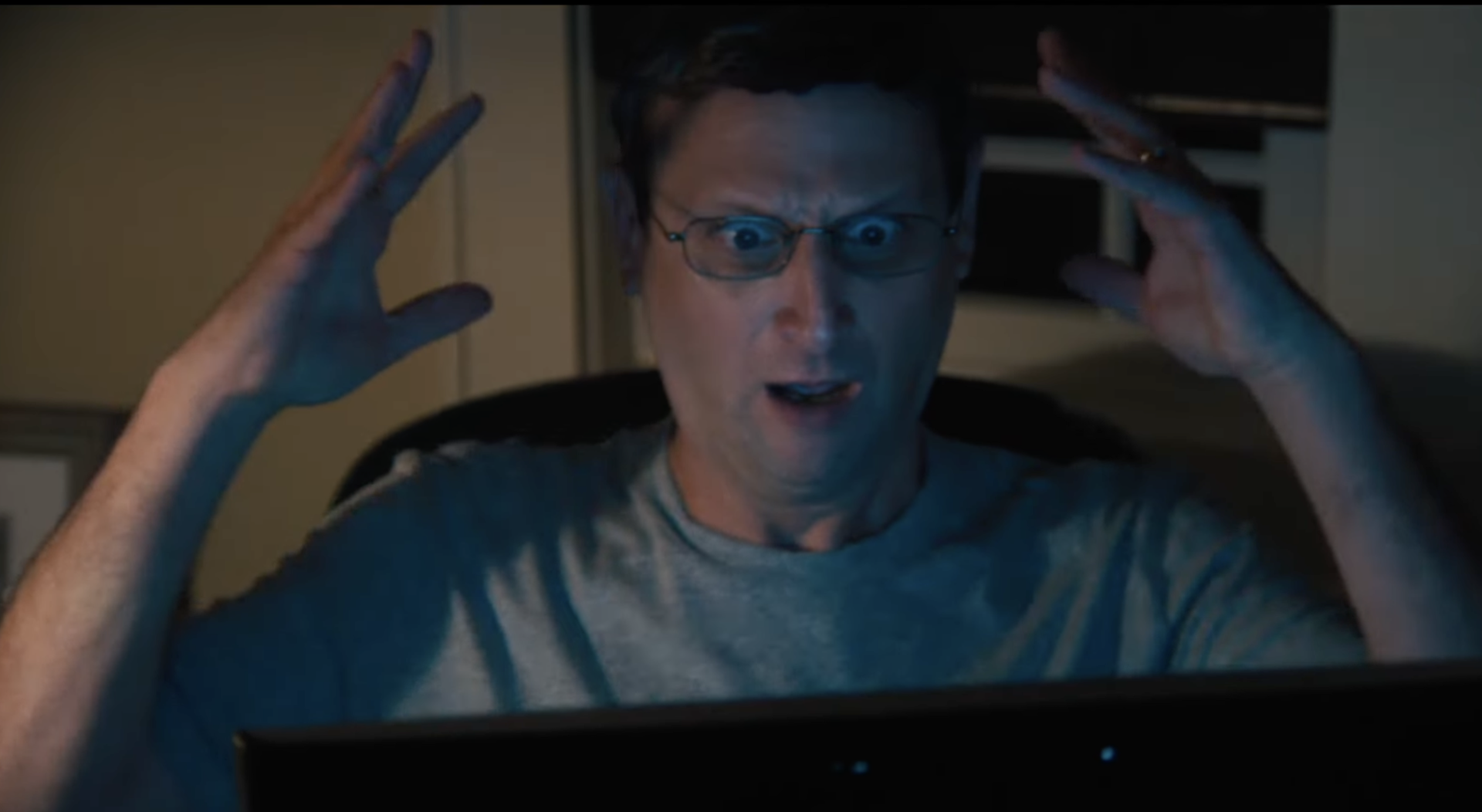

Ron Trosper traversing the site footer is maybe the most important early indication of who he is, and what a large part of The Chair Company is about. Every episode of The Chair Company features some depiction of computer usage that, while totally common in real life, is rarely acknowledged. It’s clear he finds this type of digital detective work invigorating. Often when Ron is smiling widest in The Chair Company, he’s sitting at his desk in front of a glowing monitor.

If you were to only learn about the internet through the way it is depicted in popular entertainment and in reporting on technology and online behavior, you might think that there are exactly two types of people:

1. People who spend time online on a handful of social media platforms, producing or passively consuming algorithmically optimized, low-quality dreck and developing, as a result, a shallow or misshapen view of reality. An “extremely online” (dumb term btw) cohort of memers, shitposters, content creators, gooners, internet Nazis, humorless SJWs, Instagram models, citizen journalists, algorithm-powered conspiracy theorists, TikTok dancers, Twitch streamers, and podcasters competing in a never-ending race for attention by any means necessary.

2. People who do not know how to use a computer at all.

The Chair Company is the first show I can recall that understands the gulf between these poles, and revels in it. It makes the case that efficiently sourcing and parsing online data is not exactly a universal skillset, but it is one that millions of mild-mannered, middle-aged office workers and an ever-increasing population of lifelong computer users possess, the result of having existed in a world where the world wide web was actively expanding instead of centralizing on mega-platforms. It also draws a clear connection between online and offline behavior, rather than conceiving of them as separate spheres.

The makers of The Chair Company also seem aware that while much of what is on the world wide web is publicly accessible, it is often not optimized to be easily found. I have grown to eagerly await each week’s scene in which Ron sits down at his computer or picks up his phone and feels the subsequent rush of an extended session of forensic web-surfing. I have some experience with this activity, having written about internet culture with some regularity for over a decade. This reporting method relies on an unscientific mix of deductive reasoning, advanced search operators, and the brute-force ability to scan countless blog posts, amateur videos, comments sections and replies, and the Wayback Machine for information that has not been highly ranked by search engines or synthesized by AI models. I have used these open-source intelligence techniques to find incredibly stupid shit: the man who backflipped into a neon sign at Krispy Kreme, the man who front-flipped off a dock while pooping, the real identity of DeuxMoi, the pre-fame posting history of Lil Nas X, the origins of a Tumblr-famous rat named Neil, a child who got hit in the head by a basketball in the mid-90s, and the address of a beautiful mansion that also features an extremely ugly Simpsons mural—to name just a few and establish my credentials on this topic.

In the show’s pilot, Ron feverishly searches for information on Tecca, a chair manufacturer who has failed him personally, and finds little of value. The company’s website is generic, full of stock images and empty corporate prose. The phone number listed goes nowhere, and the chat support pop-up is obviously staffed by a bot. It responds with a dispassionate “I don’t understand” after being called a “Fucker.” Then he starts really getting into it, doing the real sicko stuff. He scrolls down to the Tecca footer and clicks through every link on their sitemap. He reads the shipping policies, the FAQ, and the terms of service. (“Tecca may share your personal information with trusted third-party service providers, such as shipping companies and payment processors, to facilitate order fulfillment and payment processing.”) He clicks to a page about the site’s accessibility features before finally finding a support email alias buried in a page on Ohio’s state-specific online privacy rights. He sends the alias a message and—as often happens when you try to send something to an email buried on a corporate website that is so excessively bland that it feels fake—his message bounces back as undeliverable. It is the most relatable thing I have ever seen on television.

My favorite joke in the season is when a stumped Ron clicks on a website’s search box and types in “Maggie S,” a woman he’s looking for. Searching for a person by their first name and last initial will never, ever yield results, and I can say this as someone who has probably tried the same tactic a million times. “What am I doing?” he asks himself.

You could say that this behavior is not particularly interesting or compelling, but I’d disagree. It depicts a type of mundane proficiency rarely shown in detail in popular media and, more importantly, it is a dying art. For years, the web was something to be explored, clicking hyperlinks and bouncing between sites, but is now the domain of the mega-platforms, which have been perfecting their recommendation algorithms to keep users captive inside walled gardens. Videos autoplay one into the next; links to external sites are buried; those feeds are personalized to serve up a perpetual high-throughput current of low-effort engagement bait. Once, these sites were easily indexed by search engines and their data could be easily inspected with open APIs, but now the APIs have closed up and everything is guarded by a login screen and a robots.txt file.

The websites that aren’t mega-platforms are trying their best to avoid being abused by AI scrapers. If a user wanted to dig through the world wide web themselves, they’d have to fight most major search engines to do so, since AI systems keep offering—insisting—to do it for them. The simple ability to make a choice about which sites to check out while surfing the web is dying off, replaced by “agentic” tools that make decisions on behalf of users about where the most useful information lies. Where, Ron Trosper might ask, is the fun in that?

The Chair Company is deliberate in depicting the desperate minutiae of going down an online rabbit hole. In the second episode, we see Ron take a picture of an intriguing shirt on his phone and wirelessly send it to his desktop, where he retrieves it from his file browser in order to reverse image-search it. He finds the shirt’s manufacturer, heads down to their site footer in order to get to a store locator, copies the closest location’s address to his clipboard, and pastes it into Google Maps. He adds it as a third destination in the directions sidebar and then drags it to second in the list, so that he can see how long a detour to the shirt store would take on his way to a work appointment. Part of the reason these sequences work is that they depict realistic human-computer interaction instead of employing the computer as a device of extreme convenience (how many times have you seen a character google someone, only to find a perfect, explanatory news article or social media profile in the top slot?) or conflict (a malicious program/hacker/online mob makes someone’s life suck). Oddly enough, the least dramatic option—showing a detailed version of web browsing that the audience can identify with—is its best source of dramatic tension.

Throughout the season, Ron performs plenty of other uniquely digital maneuvers. He ties two disparate websites together later in the season by noticing a shared color scheme (the man who designed both put a smutty and oddly specific reference in its CSS). He suffers the indignity of ordering some overpriced Temu-like crap from Amazon. He accidentally rescues a runaway dog and then farms clout by asking the owner to post a pic thanking him on Instagram, where the commenters are not pleased. His big project at work is backseat-managed by online detractors. He is pestered by a members-only group chat he is pressured into joining at the shirt store. The messages arrive via group text and email listserv.

Chasing a man through a basement, he opens a door to find two people getting intimate, and is forced to become an unwilling minor participant, almost as if he performed the real-world equivalent of clicking a bad link and getting bombarded with endless pop-ups. As a story, The Chair Company is messy and inconsistent, and can sometimes feel like half-baked I Think You Should Leave Sketches connected by a loose narrative. But it is that shagginess that makes it a useful vehicle for the story it tells under the surface, of a man who cannot stop letting the internet lead him into absurd, inexplicable trouble. In fact, he seems to enjoy it.

Not once but twice in this first season, Ron breaks into someone’s home to gather useful information, and each time, he enters a room and is confronted by what I can only describe as “weirdos screaming at him.” He scurries around the first, a hoarder house, frantically grabbing at random papers. In the second, he fights a group of angry men while trying to acquire an iPad containing a crucial email address. To anyone who’s spent any time trying to find the near-unfindable online, it’s not exactly a subtle metaphor.