You really have to feel awful for them. The health care workers, I mean—the 550 of them who, after 15 months of hell, were "rewarded" by being the first fans let into the building for a Maple Leafs home game this season, only to watch the Leafs complete a bed-shitting as messy and grim as anything we've seen this decade, even by Toronto's lofty standards. Thanks for saving lives, health care workers, but this one's flatlined.

So that's that, then, the highly favored Maple Leafs are out, falling in seven games to the Canadiens after being up 3-1. It's not the NHL's first 3-1 series collapse (it's the 30th), and it's not the Leafs' first opening-round loss (it's their, uh, fifth in a row), but it was as painful and as foreshadowed as any of them. And it's really not clear where the Leafs, hard up against the cap, and with a denuded draft and not much in the way of incoming prospects, go from here.

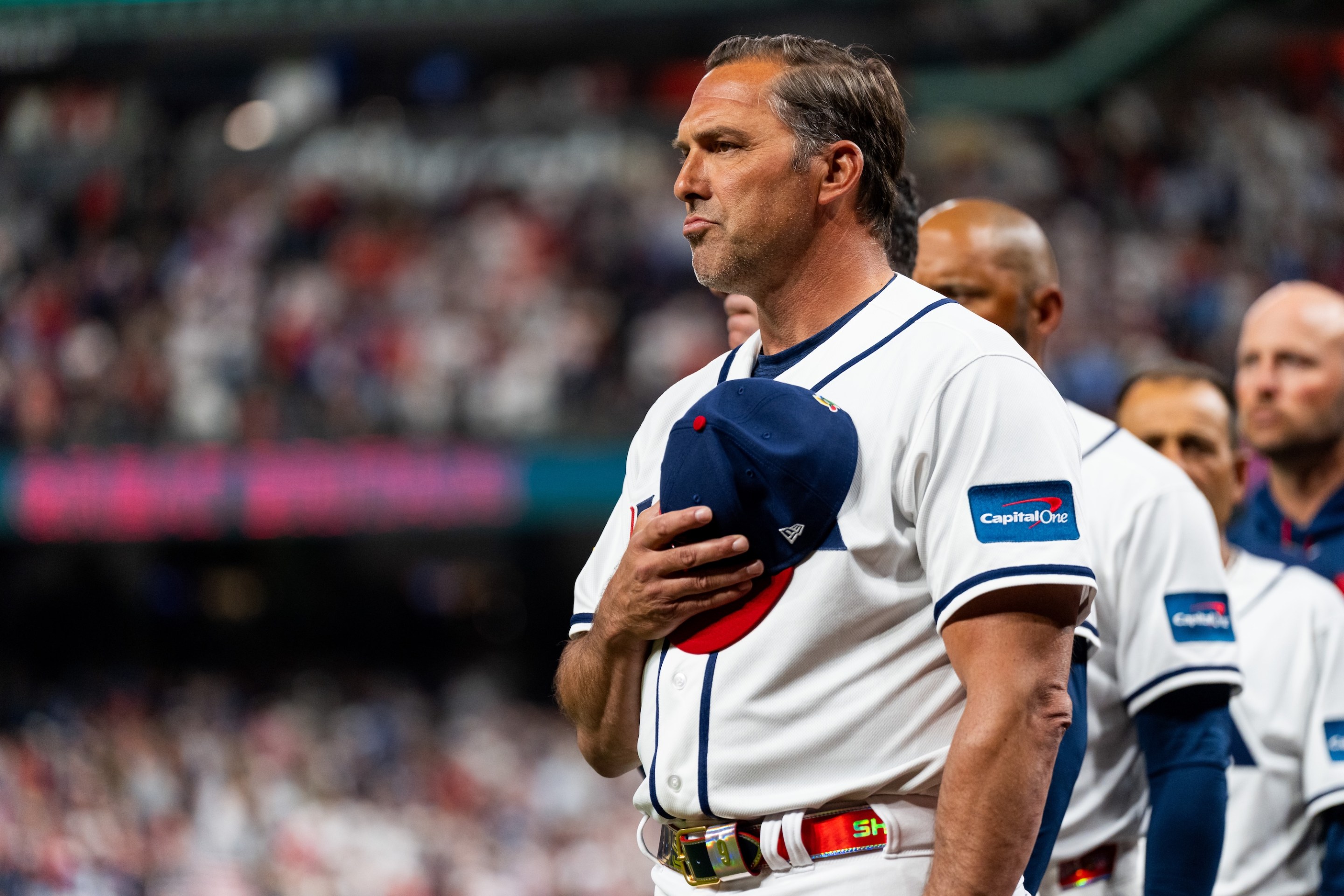

"We’re obviously devastated, disappointed, expected better of ourselves, felt we were capable of a lot more," Toronto coach Sheldon Keefe said. "Not just tonight but through the whole series.”

Not many Leafs beyond Willie Nylander, Jack Campbell, T.J. Brodie, and Jason Spezza did much worth writing home about this series, but the lion's share of opprobrium is necessarily going to fall on Mitch Marner and Auston Matthews, who finished fourth and sixth in the league in scoring in the regular season but combined for just one goal against the Habs. That criticism is certainly earned, even if Leafs fans may take it too far this summer when they descend on Marner's apartment with pitchforks and torches. But the Leafs' true vulnerability was sealed long before two of their biggest weapons turned into popguns against Montreal.

The Leafs, by design, operate on the star system—the four-star system, to be precise. Matthews, Marner, Nylander, and John Tavares are the bulk of their offense, and an enormous chunk of their payroll. The four players lock up around $40 million of cap space among them, which, to put it bluntly, doesn't leave much cash for supporting talent. The Leafs have been forced to rifle through the discount rack for depth, and landed on a number of veterans who bring things like "grit" and "experience"—intangibles, basically, which is a polite way of describing things you don't have to pay much more than league minimum for. Did Toronto go out and get the likes of Wayne Simmonds, Joe Thornton, and Zach Bogosian because they bring something to the dressing room, or because they were cheap? The front office would probably claim both, but for whatever they brought to the dressing room, they didn't bring much to the ice.

Here's the thing about frontloading your talent and your payroll: there's no parachute. If, for example, Tavares gets hurt, and Marner plays spooked and invisible, and an opponent is able to focus on shutting down Matthews because his linemates aren't worth worrying about, there's no backup plan. Four threats quickly become just one, and there's nobody to step up to replace them. Depth is about a lot more than the odd goal from a fourth line. It's about understudies, and the Maple Leafs simply don't have any.

They could've, though. The biggest what-if of the season may end up being the trade deadline, when disgruntled but elite Taylor Hall went to the Bruins—for not very much!—while the Leafs, rumored to be in on Hall, ended up paying more to land Nick Foligno. Yes, Foligno seemingly made sense for what Toronto was looking for, for his toughness and his track record, and yes, Hall may have been focused on Boston because they have the capability to re-sign him (there's that pesky salary cap again) but the math is pretty stark: Hall has scored 11 goals for the Bruins in the regular season and playoffs, while Foligno had [punches buttons on calculator] [fumbles with protractor and compass] [pretends to know how a slide rule works] zero.

I'm not sure if it makes it more or less galling to understand that this state of affairs was something close to inevitable. A full tank-and-rebuild like the Leafs undertook, if successful, results in a series of high draft picks. And those picks, if successful, turn into talented players who need sizable second contracts, all around the same time. And when the young team is ready to compete, they lay out for a big veteran contract like Tavares's. Again this is the successful version of this plan. But it still resulted, for various reasons both in and out of the front office's control, in $40 million being locked up in four guys. That's excessive among contenders. Take the Avalanche, who look like world-beaters, and are paying roughly $26 million to their top four earners. Or the defending-champion Lightning, with cap issues of their own, who have committed about $32.5 million in their top four.

The problem is real for the Leafs, and it's not going away on its own. They're not going to find scoring depth or talented defensemen in free agency, because they can't afford them. (That many, many NHL teams would eagerly trade their current situations for the problem of having four stars probably isn't much consolation for Toronto.) So the question becomes, what can be done?

Trading Marner will be the popular solution, at least on sports talk radio, and it feels like a realistic outcome if the Leafs are looking for some better-balanced scoring. He's not going to bring back anyone quite with his talent, but he could fetch multiple skilled players and more flexibility. That's one option. Another is to trust in this roster but make a change behind the bench, if the ruling is that Keefe, after two abbreviated seasons, hasn't shown enough ability to adapt his gameplan to what his players and his opponents are offering. Maybe there's something to that: Toronto didn't seem to have any answer for Montreal stacking its blue line, and it really shouldn't be that simple to shut down this Leafs offense.

Or maybe what's broken in Toronto is so fundamental that blame can only fall on the top brass. Maybe it's been enough time to judge what team president Brendan Shanahan and GM Kyle Dubas have built, and to declare it faulty. They gave it a run, and made something decent, but what if the Shanaplan resulted in something that's just not quite good enough? But making a change in the front office doesn't immediately address the issues on the ice, and it's not as if this team is about to engage in another rebuild while Matthews is in his prime.

No, franchise-level change probably isn't in the cards in Toronto. Instead, you're going to see more spare parts being changed in and out, more attempts to find gold in the bargain bin, more tactical experiments, more reshuffling of assistant coaches—the sort of things a team does either when it thinks it's close to a Cup, or because it can't afford to do anything else. Maybe both. "Stay the course" as a strategy proved the right one for Tampa after their stunning first-round choke at the hands of Columbus in 2019, and maybe it's the right one for Toronto. But what, exactly, is the course the Leafs are on right now? Come the postseason, at least, it rarely looks like one worth following.