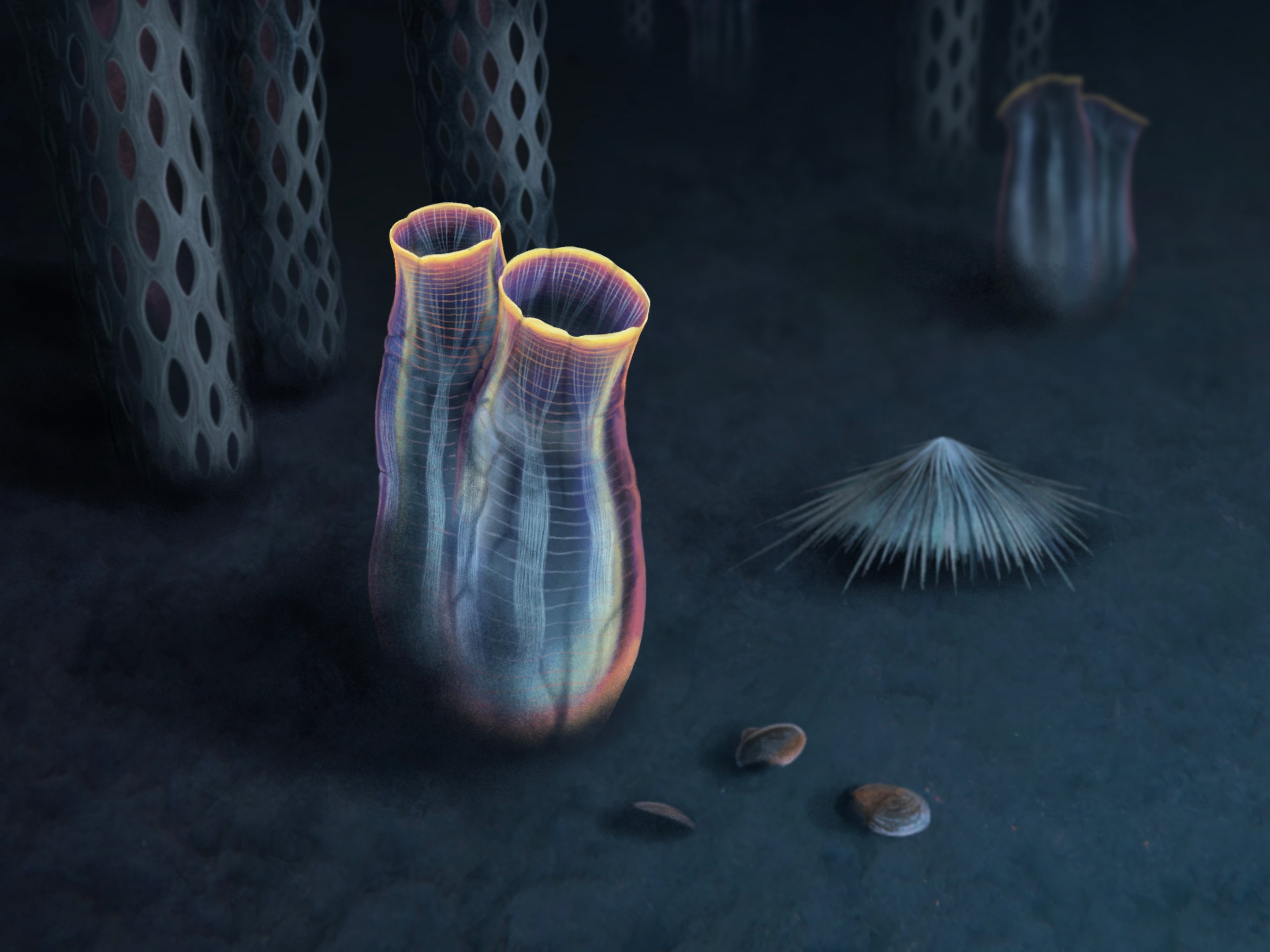

In adulthood, the sea squirt Ciona intestinalis resembles linen intestines, sheer tubes spilling out like a grisly bouquet. But a baby Ciona sea squirt looks more like a tadpole—swimming freely in open water until it finds a hard place to attach. The larva's squishy body is elongated by a notochord—a flexible primitive backbone shared by all chordates, a group that includes all vertebrates. Once a larval Ciona finds an ideal home, its body transforms, absorbing its notochord and becoming a tube-like adult.

Sea squirts like Ciona are one of two types of marine invertebrates called tunicates, which are our closest invertebrate relatives. While sea squirts remain stationary, rooted on hard places, the other type of tunicates jet around the open seas, and include salps (sometimes called sea grapes), pyrosomes (sometimes called sea pickles), and larvaceans (these do not have a cute nickname but do build houses made of snot). These very different lifestyles made scientists wonder: Were the first tunicates free-swimming or bottom-dwelling?

Now a group of researchers have found a 500-million-year-old fossil that looks just like a modern sea squirt, which they describe in a recent paper published in Nature Communications. The fossil, dubbed Megasiphon thylakos, suggests that the ancestors of tunicates were bottom-dwellers. This discovery offers new evidence for the evolutionary history of tunicates and pushes back the very origin of the basic vertebrate body plan by 50 million years, according to Chen Cao, a researcher at Princeton University who was not involved with the paper.

"I have to admit, it is quite an extraordinary finding," said Federico D. Brown, an evolutionary developmental biologist at the University of São Paulo who was not involved in the new paper. "Tunicate fossils are extremely rare and several published ones have been heavily scrutinized," Brown said, adding that Megasiphon is the most sea-squirt-like fossil he's seen reported yet.

Javier Ortega-Hernández and Rudy Lerosey-Aubril, both invertebrate paleobiologists at Harvard and authors on the paper, first encountered the fossil in the spring of 2019 while poring through the collections of the Natural History Museum of Utah. Ortega-Hernández works mainly with arthropods, whose hard exoskeletons often fossilize neatly. But he pulled out a chunk of mudstone, he saw a fossil that looked quintessentially like a tunicate: like a vase with two spouts. "How weird," Ortega-Hernández thought to himself.

He passed the fossil to his colleague Karma Nanglu, a paleontologist at Harvard University and the Museum of Comparative Zoology and an author on the paper. Nanglu self-describes as a "worm guy" but will be the first to tell you that worms aren't real, at least as far as taxonomy is concerned. (The creatures we call worms belong to many groups, but share the classic body plan of a tube with no limbs.) Unlike most of their colleagues, worm paleontologists have very few fossils to study. "They disappear most of the time," Nanglu said. "You're decaying away at the speed of light." So Nanglu had to familiarize himself with other under-appreciated invertebrate groups, like tunicates. "Like a worm, you have to kind of like find a little bit of interstitial space for yourself that hasn't already been taken," he said.

When Nanglu heard Ortega-Hernández might have stumbled upon a tunicate fossil, he wanted to keep a skeptical eye. "There's a lot of stuff that looks like a lot of stuff," Nanglu said.

The fossil record of tunicates is barely a record at all. Ausia fenestrata, a colander-like fossil from the Ediacaran period, has been inconclusively interpreted as a coral, a sponge, and a tunicate. The puzzlingly fin-shaped Scottish fossil Ainiktozoon was initially thought to be a kind of tunicate until it was redescribed as an arthropod. And most putative tunicate fossils don't preserve the whole body, only tiny structural hard parts called spicules. In 2003, a group of researchers identified a fossil, Shankouclava anningense, discovered in south China as an early Cambrian tunicate. "But if you look at the fossil, it doesn't really look much like a modern tunicate," Nanglu said. "It doesn't look much like a tunicate at all."

Megasiphon, however, looks just like a modern tunicate. Resemblance alone isn't proof, so Nanglu examined the fossil under a microscope and considered alternate identities for the fossil. Could it be the fragment of another creature? A branching algae? The burrow or excreted tube of an ancient worm? But no Cambrian creature had a body part like this, and the the fossil bore no resemblance to known Cambrian algae. Plus, it had preserved soft tissue, meaning it was not just a burrow. Nanglu saw the fossil was streaked in dark bands running from the base of the fossil to the tips of the two siphons, which he recognized as musculature similar to the modern tunicate Ciona intestinalis. He scoured the literature for photos of modern tunicate muscles for comparison but found none.

"Karma took it upon himself to go like, 'Well, let's order some tunicates from Woods Hole and we will do nasty things to them,'" Ortega-Hernández said glumly (one of the advantages of being a paleontologist, he clarified, is never needing to euthanize your specimens). Nanglu dissected the tunicates and found beautiful bunches of muscles arranged just like the bands of the fossil. "They kind of unspool to individual fibers when you get to the tips of the siphons, and you can see they're finger-like, almost arranged like a pitchfork," Nanglu said.

Other muscles did not preserve as well in the fossil, such as the ringed muscles that surround the siphons of modern tunicates, Brown said, adding that with just the single specimen, he does not believe the fossil can be conclusively identified as a tunicate.

But to Cao, Megasiphon's "unprecedented well-preserved soft tissues including nuanced muscle structures and two siphons clearly represents the modern tunicate." Cao suggested the authors examine the fossil with advanced microscopy techniques to study any chemical elements that might be preserved in the ancient tunicate's tissue. Tunicates can absorb trace elements from seawater, making them excellent indicators of their environment. Such a study "may help look back to their living niche of the Cambrian world," Cao said.

Megasiphon offers fresh evidence that the earliest tunicates were bottom-dwelling like modern sea squirts. This, combined with recent molecular estimates, "suggests the free-swimming lifestyle evolved independently multiple times in tunicates, which is an exciting hypothesis to consider," said Melissa DeBiasse, a project scientist at the University of California, Merced, who was not involved with the paper. "Evolution is not always linear, and traits can be gained and lost in complex ways."

But this would also crack open a new mystery. If tunicates have been around for 500 million years, where are all the fossils? The Utah formation that entombed this tunicate—likely via a sudden, silty underwater avalanche—has preserved many other soft animals. As Hernández-Ortega continues to sort through hundreds of the museum's fossils, he has yet to see anything else resembling a tunicate. "We think this is truly a unique singleton, and, you know, it may be that these things were incredibly rare," he said. Unfortunately for paleontologists, the Cambrian may have been a lonely time to be a tunicate. Fortunately for tunicates, a lack of a true brain means they probably weren't sad about it.