Saturday marks 48 years since Elvis Presley was found dead inside a Graceland bathroom. And so, for the 48th time, his devout followers are gathering in Memphis for a week of concerts and various other events commemorating the King, who'd be 90 years old were he still alive. Clearly there’s still some juice to squeeze out of the King’s carcass: Tickets for Monday’s tour of Elvis’s big house—hosted by one of his last girlfriends, Linda Thompson—sold out at $7,000 per set of four.

I’ve been among the memorializers. Of the many rock and roll pilgrimages I’ve taken through the years, none combined irreverent and reverent quite like my 1990 trip to what was then commonly called “Death Week” before Elvis Presley Enterprises rebranded the tribute with the far less metal moniker, "Elvis Week."

I’d grown up at a time when Elvis was mostly a punchline. My album-obsessed parents didn’t own a single Elvis record, and since he only had one Top 10 hit in the 1970s while I was cutting my musical teeth—“Burning Love” in ‘72—I almost never heard him on the radio either. The reviews of his concerts in the D.C. area when I was a kid were brutal. Sally Quinn, the Washington Post’s haughty socialite columnist, covered his show at the Capital Centre in June 1976 and included heinous observations that, according to her, have “just got to be said.”

“Elvis is fat,” Quinn wrote. “Not only is he fat, his stomach hangs over his belt, his jowls hang over his collar, and his hair hangs over his eyes.”

And there were plenty of jokes about his show in Baltimore in May of 1977—the one where he reportedly paused to take a half-hour dump. (Banana splits— plural—were blamed for the King’s colonic distress.) Talk about foreshadowing: The guy died on his dang toilet less than three months later.

So it wasn’t easy to be a young Elvis fan at that time. I was more into other sorts of rock and roll, and none of my friends gave a rip about him either. On Aug. 16, 1977—the day he tried to take his last poop—I was at the Capital Centre with a bunch of neighborhood kids, watching the English prog gods Yes. Same arena where Sally Quinn had called Elvis was fat and unkempt. Nobody onstage mentioned that the King had died.

And yet, I still remember how happy Elvis made my Mr. Parks, a wonderful guy who lived next door to me growing up. He came of age in D.C. in the '50s and had a lot of Fonzie in him. He made sure everybody on the block knew of his love for the King. The first time I got it was when he played me “An American Trilogy” from the double-live Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite album. Elvis turned cheese into gold—right before my ears.

The older I got, the more sense Mr. Parks’s deification made. I eventually wised up enough to recognize the obvious things: Yes, with all its art-rock bombast, was merely of its era. Elvis, on the other hand, is timeless. I started reading and listening to whatever Elvis material I could get my hands on. I hounded people whose lives were changed by early Elvis and got them to tell me their stories. I found everything about young Elvis fascinating.

But even the ‘70s King—the physically bloated, commercially irrelevant guy in sequined jumpsuits, circling the drain—rocked my world. Anyone who doubts that Vegas-era Elvis was still a genius only needs to hear “That’s the Way It Is,” a box set from his 1970 Las Vegas Hilton residency. The recorded backroom rehearsals alone show how profoundly touched by God he was.

So I made that trip to Memphis in 1990 with massive amounts of awe for Elvis's talent and world-changing impact. But I still embraced all the kitsch. I used a hardshell guitar case as my suitcase, and requested and received the discounted “recording rate” at a downtown hotel, a bygone perk of the city’s past as a recording mecca. Death Week observances had started as small candlelight vigils on the one-year anniversary of his passing, but by the time I went, the event was drawing 40,000 visitors annually. The city was packed during our stay.

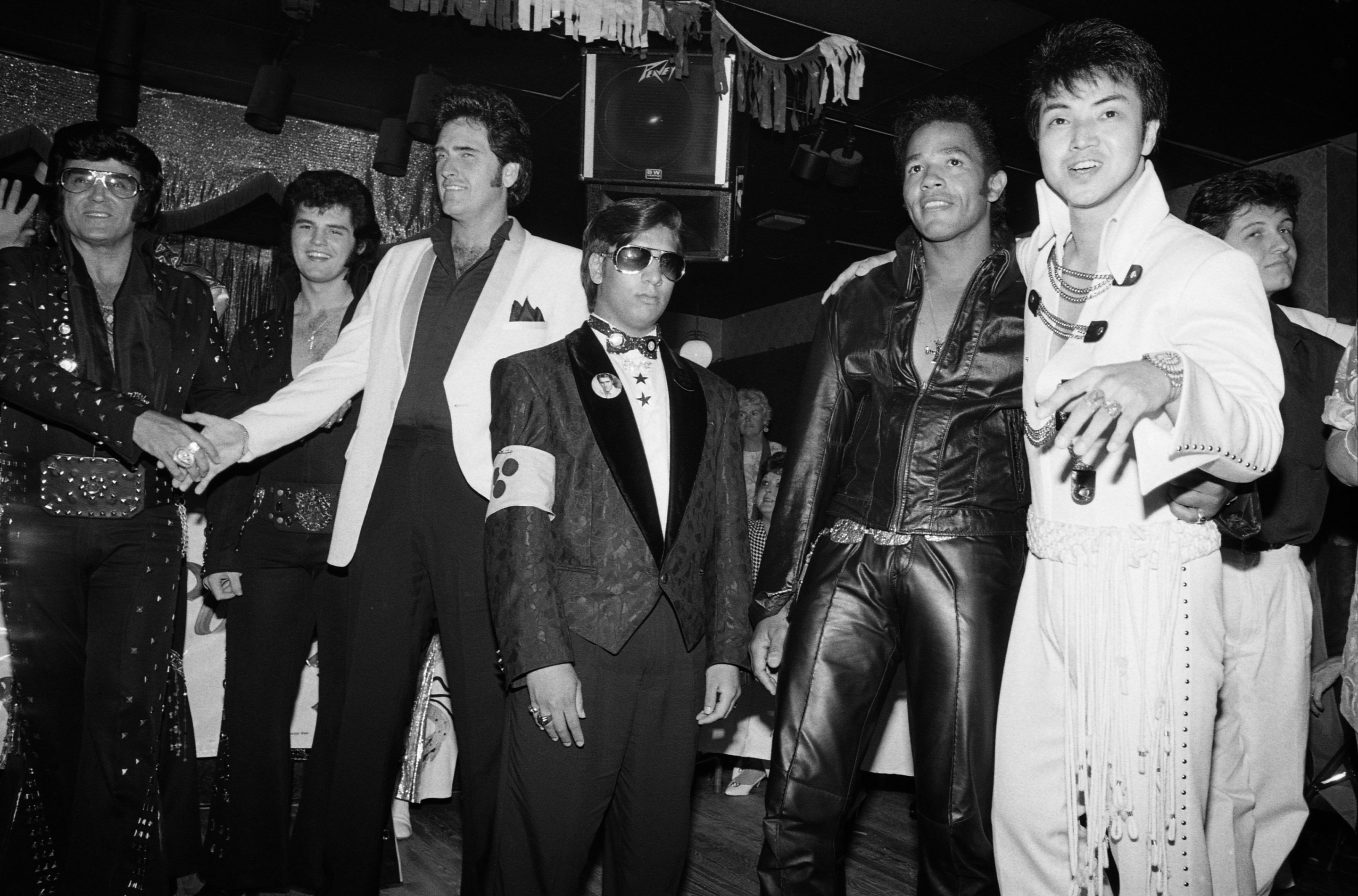

There was no downtime. I toured Sun Studio where, in the summer of 1953, Elvis and producer Sam Phillips began recording the songs that would change music history. I spent a night at Bad Bob’s Vapors, a legendary Memphis honky tonk, catching a portion of the almost-endless Elvis impersonator contest. The whole time I was at the jaw-dropping extravaganza—which featured one professional imitator after another, night after night for a whole week—I kept hoping that Jerry Lee Lewis, a local known to patronize the club, would crash the party the way he crashed through the front gates of Graceland in his Cadillac, drunk and jealous, waving a gun and demanding an audience with Elvis back in ‘76. But no such luck. No sighting of the Killer during this Death Week.

I did, however, catch a set from El Vez at Vapors. He’s the Mexican Elvis—a Southern California performer named Robert Lopez—whose Spanglish and PG-13-rated parodies of the King’s classics disgusted all the blue-haired ladies who made up the bulk of the Death Week demographic that year. (Mr. Parks wouldn't have approved either.) Small wonder El Vez didn’t win the contest.

I made the mandatory visit to Graceland but didn’t brave the hours-long line for the official tour. My review of the King’s house, having never been inside the Jungle Room: way less ostentatious than I woulda guessed! Instead, I shopped at Graceland Plaza, a strip mall owned by Elvis Presley Enterprises, located just across the street from Graceland. Every store was dedicated to only Elvis-related merchandise. I left with a suitably glittery Elvis Christmas ornament.

I went to an Elvis symposium at Humes High School, his alma mater, where he graduated with the Class of ‘53. The most memorable panelist was Pauline Nicholson, the cook at Graceland. During the Q&A, I asked what the King's daily breakfast menu consisted of. I remembered her response was nauseating. I just rewatched video footage that Rick Morris, a guy in our Death Week entourage, made of the trip to check if my memory was accurate. The actual calorie count was more horrific. Nicholson said he would have “eight or 10 biscuits,” plus “a pound of bacon or a pound of sausage with about six eggs.”

“We’d try to cut it down,” she insisted, “but we better take him six eggs.”

At the opposite end of the health spectrum, I ran in the Elvis Memorial 5K (28 minutes and change!), an official Death Week event to this day. I was only in it for the T-shirt—which I still have somewhere in the basement.

I also did plenty of non-Elvis stuff. On the subject of Kings, I visited the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. At the time, the building was then rotting away. There, I met Jacqueline Smith, a former tenant who had just begun what would become a one-woman, around-the-clock protest lasting over 30 years, demanding that the planned memorial onsite properly honored MLK's legacy. (There’s no record Elvis and MLK ever met, but Elvis did perform a tribute to the civil rights leader—“If I Can Dream”—to close his 1968 comeback special, recorded a few months after the assassination.)

I also went to the Full Gospel Tabernacle Church, founded in 1976 by another Memphis legend: R&B singer Al Green. I’m not a godly man, but—like so much of the trip—the memory of that service still drops my jaw. Al Green himself led it, the only time I’ve ever seen a church band guitarist plug into a full Marshall stack. On Death Week Sunday, the only non-Black parishioners in the building were me, my buddies, and El Vez.

El Vez won’t be in Memphis for this year’s tribute, but he’s still honoring Elvis in his way. He told me via email that he was excited about the show he did in San Diego over the weekend with Lenny Kaye—the guitarist best known for his work in the Patti Smith Band when the King was still among us. I gotta say, that sounds like the makings of a promising collaboration. As Patti almost put it, “Elvis died for somebody’s sins, but not mine…”