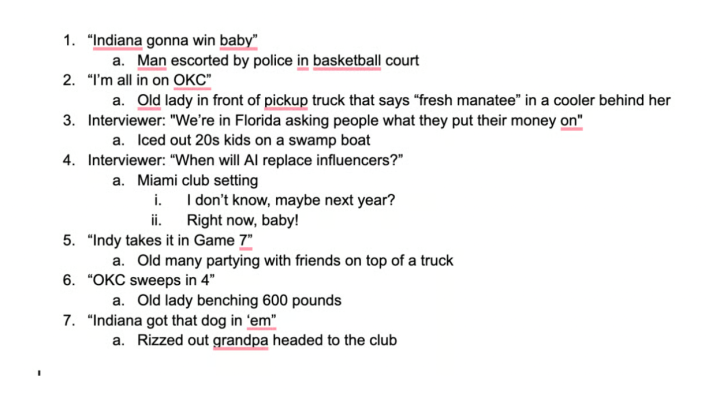

During last summer's NBA Finals, a fully AI-generated commercial featuring people in man-on-the-street interviews yelling toward the camera about all the things they were going to bet on (football games, the price of eggs, hurricanes, alien visitations) introduced the world to Kalshi. Tagline: "The world’s gone mad, trade it." The ad was made by “AI filmmaker” PJ Ace, who wrote a brief outline of the concept and then had ChatGPT convert it into a more detailed prompt, which he then fed into Google’s VEO 3 video generator:

The decision to rely on generative AI wasn’t about saving money—Kalshi is and was extremely well-capitalized—but about flaunting a certain kind of trollish, accelerationist posture intended to locate their target audience: people on social media who are very certain about their ability to predict the future.

Kalshi—an Arabic word meaning everything—is a "prediction market" where you "trade" (an important linguistic slip vis-a-vis "gamble") on "future event outcomes." As of right now, I can buy shares of either "Yes" or "No" on whether or not Ali Khamenei will remain Supreme Leader of Iran, who the winner of the Super Bowl will be, the over/under of the Rotten Tomatoes score for the movie Primate, what cities Trump will send the National Guard to by 2027, whether or not Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce will still be married by then (and if Taylor will appear on Call Her Daddy), how many whooping cough cases there will be this year, and what the maximum extent of the Arctic sea ice will be this winter.

I can also bet on who will win the 2028 presidential election, a type of gambling that was illegal in the United States until Kalshi won a D.C. Court of Appeals ruling in September 2024 that overruled a previous Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) action against them. The CFTC voluntarily dropped their appeal in May of 2025, prompting Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour to declare triumph: “Today is historic. We have always believed that doing things the right way, no matter how hard, no matter how painful, pays off. This result is proof of that. Kalshi’s approach has officially and definitively secured the future of prediction markets in America.” The last part is likely true—the ruling rested on redefining Kalshi’s operation away from “gaming,” removing any authority the CFTC has over it, and paving the way for Kalshi’s ongoing operation in all 50 states, even in places that have not legalized traditional forms of gambling or online sports betting.

Mansour, formerly of Palantir, cofounded Kalshi along with fellow MIT grad Luana Lopes Lara, a brain and cognitive science researcher and former quant for Citadel Securities. The two hired Donald Trump Jr. as a strategic advisor early on, and the first board member other than themselves was Brian Quintenz, Donald Trump’s former commissioner of the CFTC and rumored to be his next pick to head the department once again. Getting the CFTC off their backs was clearly the company’s primary objective, and they have since bankrolled tremendously off of their success; in November of 2025, Kalshi told its investors that trade volume had increased sixfold over the months since the CFTC dropped their appeal, and that it was pacing $600–700 million in revenue. Another month later and they raised $1 billion at an $11 billion valuation, with Lopes Lara making headlines for becoming the world’s youngest self-made woman billionaire at age 29.

Riding high amongst all their success, Mansour and Lopes Lara appeared on a Citadel Securities panel, titled “Turning Events into Assets,” where Mansour did his best showing of the disaffected-founder vocal fry, laying out the future of Kalshi with the aloof self-certainty that has become grating cliche in Silicon Valley. “The long-term vision is to financialize everything and create a tradable asset out of any difference in opinion," he said. "If you do create this, the TAM [total-addressable-market] is quite massive, quite a bit bigger than the current stock market.”

It’s a straightforward way to read Kalshi: an inevitable progression or even endpoint of the U.S.'s long road of financialization. You can chart the growth of prediction markets closely with the rise of so-called "retail investing," trading done by everyday, non-professional individuals that buy small amounts of stock or crypto, mostly on their phone. This kind of investing has grown exponentially in the last 10 years—it rose 50 percent between 2023 and 2025 alone. An analysis from JPMorgan found that “the share of 25-year-olds in 2024 that used investment accounts was 37 percent, versus 6 percent of 25 year olds in 2015,” adding, “this trend, amid a decline in those becoming first-time homeowners, suggests a potential change in wealth accumulation patterns, in which the stock market plays a bigger role in people’s financial lives relative to prior generations.” The analysis also showed that lower-income individuals have increased this investment activity more than higher-income individuals, likely reflecting people priced out of traditional assets looking for somewhere else to get a return.

You can see how the true believers can twist themselves into welcoming the proliferation of prediction markets as a win for those lower-income individuals—besides, isn’t the stock market itself a "prediction market," only obfuscated and gatekept by U.S. class mechanisms and the protectionist rituals of Wall Street? Shouldn’t we be celebrating proletarian access to investment instruments? Just look at the name of the leading retail investment app: Robinhood. Read Kalshi’s in-house blog after securing election gambling: “Previously, election hedging was a privilege reserved for large corporations and the wealthy elite. But thanks to Kalshi, everyone has the right to protect themselves from the uncertainty inherent in the democratic process.”

The problem for the little guy is that so far in their very short history, prediction markets have been breeding grounds for new and more debased forms of corruption and insider trading than possibly even the stock market. In a Coinbase quarterly earnings call last October, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong said, "I just want to add here the words Bitcoin, Ethereum, blockchain, staking, and Web3 to make sure we get those in before the end of the call." A total of $84,000 had been wagered on prediction markets in the so-called "mention markets" for various words that would be said on the call, including those he listed off. Hours before Mariá Corina Machado was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, chances of her victory skyrocketed on prediction markets, with Norwegian officials claiming the highly secretive selection process may have been a victim of espionage. In December, a Polymarket (Kalshi’s biggest competitor in the space and official prediction market of Elon Musk’s X) trader made over $1 million betting with exacting accuracy on Google’s 2025 Year in Search, again just hours before their release to the public. And most recently, in the lead-up to Nicolás Maduro’s kidnapping by the U.S. military, a newly created Polymarket account wagered a total of $30,000 on Maduro’s ouster—its final bet just five hours before Delta Force hit Caracas—and pocketed over $400,000 in winnings.

This kind of activity is so frequent that there are now people looking for signs of insider activity to try and piggyback off of as an investment strategy—earlier this month, four brand-new crypto wallets all placed four-figure bets on the U.S. striking Iran before Jan. 31, 2026. The transactions were flagged by crypto-wallet monitors online and caused speculation of insider trading, or, of course, feigned insider trading meant to manipulate public opinion or influence other trades elsewhere on the market. A new kind of paranoia has emerged: When every possible event has competing lines of outcomes with money on the line, how could the perception of corruption not run rampant? On Jan. 7, a White House press briefing by Karoline Leavitt was live trading at a 98 percent chance of running over 65 minutes in length, when Leavitt very suddenly ended her remarks and rushed off the podium at 64 minutes and 35 seconds. A video of a stopwatch overlaid with her hasty exit—seeming to show her make a quick glance at what could appear to be a clock on the opposite wall just before leaving—went viral, with thousands of people claiming insider trading. It likely wasn’t; there was a total volume of just $3,400 on the market, and the biggest winner made only $186. Leavitt could have just been in a hurry and needed to be somewhere at a certain time. But who knows? Just days after the Maduro insider trading made headlines, can you blame anyone for feeling like every single moment of their unfolding reality is now a new kind of scam?

Despite all this manipulation and sowing of paranoia, Mansour assures us that prediction markets will ultimately lead us to a better relationship with the news: “The implications are very important because now you imagine the sort of layer of financial infrastructure that ends up powering the new era of financial trading, but it's also powering things like the news and how you engage with the news and how you think about the news. And, you know, what's happening in the world, and how you kind of like, in some ways, like, figure out what's the truth … these are important questions that a market-based, rational answer would do us quite a bit of good.” Lopes Lara adds that she already “gets all her news from Kalshi,” following along with the recent government shutdown. “I open Kalshi and go, wow, [it’s trading at] 21 days, that sounds like a lot,” she said. (The shutdown lasted 43 days, the longest in U.S. history.)

And for their part, the mainstream news is onboard: In December, CNN and CNBC signed “multi-year exclusive partnerships with prediction market platform Kalshi to integrate event-based probabilities across its TV, digital, and subscription products from 2026,” mirroring similar deals made by Polymarket with Dow Jones, the Golden Globes, and Yahoo, amongst others. When mobile sports gambling began exploding in popularity in the late 2010s—and it’s easy to see Kalshi as a proliferation of the "gambling on shit on your phone" that began with widespread adoption of sports betting—mainstream sports news was quick to take their sponsorship deals and plaster betting lines (once taboo, illegal even!) all over their coverage. The presence is now inescapable, and in a way, sports coverage and sports gambling have converged, with networks marketing specific lines and parlays behind their most well known public figures and brand names. Will CNN’s Jacob Soboroff soon have a Kalshi pick of the day? Will a sponsored segment from St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital implore you to take the over on diphtheria cases in elementary-school children in order to manipulate the vaccine policy of Washington insiders looking to make a quick buck on the under? Browsing the various trading markets on Kalshi signals with an almost serene clarity what other recent Silicon Valley ventures have signaled in more obfuscated ways: Perhaps America has run out of ideas.

Ultimately, Mansour’s conviction of prediction markets’ truth-telling abilities extends beyond all this, beyond the trading itself, and he lands his monologue in more epistemic terrain. “Putting aside the retail trading and the institutional trading product, there’s this separate product, which is, like, we are living in a world of abundant information, and we don’t have a good [filter]—our filter is becoming increasingly noisy, there’s a lot of noise and, like, we don’t really understand what’s real from what’s not. Prediction markets are an antidote to that.”

This view of what is real and what is not is reflective of the prediction market’s core user base: a cohort of social media power-users whose primary, essential view of reality is an unending scroll of text and video. A realm of textureless, scentless, touchless, phantasmic data that neatly sorts itself into increasingly refined and predetermined categories—in other words, the essential subjectivity of the computer. Prediction markets are born from this new subjectivity, and within their endless marketplaces create a panorama of human affairs derealized, broken into discrete events with binary outcomes. Kalshi’s introductory AI-generated advertisement, its parade of grimacing, shrieking simulacra, yawping at the "camera," served as a literal manifestation of the company's essential offering—a computer’s vision of the world.

The metaphysical reverence for prediction markets is now thoroughly in the air. Prominent crypto research firm Delphi Digital recently announced a deal with Polymarket, in their press release calling prediction markets “world truth engines” that are—guess what—in urgent need of scale and funding. Whether the religious worship of markets is sincere or some psychological protection against the hollow, barren nihilism required to submit yourself to this depravity is neither here nor there. The world’s gone mad, hardy har har.