Despite all the chaos, I’m having a pretty good year. Not only have I received both shots of a COVID-19 vaccine, but the business I co-founded with my pals last year was just compared to Mahatma Gandhi in the fucking Washington Post. Plus I have a loving wife and cute cat and Joel Embiid dropped 50 the other week.

But also it's hard to say how long I will stay here at Defector. This is because my first foray into the trading of cryptographically unique, non-fungible digital assets has proven so successful that I may be forced to quit my job and start trading crypto-collectibles full time.

I’m talking about NBA Top Shot, the relatively new online platform where clients can collect digital “moments”—basically, short highlights of plays from NBA games. You buy packs of moments and are surprised by them at random, like a pack of basketball cards that doesn't clutter up your home by actually, like, existing; there's also a secondary market for individual moments. Top Shots are digital sports cards, but powered by blockchain technology, which means they come in verifiable numbered runs (no fakes) and don’t degrade like a physical product. There are no professional grading services to pay for proof of perfection, but the digital nature of the moments means such services are not necessary. The moments will never be more or less than what they are now.

Not long ago I ignored my boss and dipped my toe into the Top Shot market, spurred on by some friends in a chat where we normally talk sneakers. I bought four packs, and got what I thought were some good moments—a LeBron James three-pointer, a Steph Curry dunk. They had low serial numbers, too—in the three digits. I put some of them up for what I thought were astronomical prices, faintly regretted wasting $45 on packs, and pretty much forgot about Top Shot at that point. This continued the now decades-long fight between capitalism, my brain, and the shot of dopamine I get when I hit “buy now” on a website.

Anyway, when I returned to Top Shot a few days later I learned that I had $1,100 in my account. “Top Shot is good now,” I decided. I put a few other moments up for sale and soon my balance had ballooned to $1,800. I'm not actually going to leave Defector—now that Top Shot is getting a bit of attention, I think my chance for casual, massive gains is over. But the experience left me eager to learn more.

I collected everything as a kid: wrestling and Ninja Turtle figures, comics, Dave Barry books, pogs, video games, whatever. My mom says I had a rock collection when I was little. I still have a collector’s mindset, no doubt, but I’ve been able to channel that energy into what I feel are enjoyable pursuits.

Everything else I liked had more of a purpose than the baseball cards I collected. I played those video games. My wrestling guys fought my turtles. I wore through the basketball sneakers I begged for. I still have those Dave Barry books; sometimes I re-read one and insist my wife simply must hear this joke about Windows 95. Pogs were at least cheap.

And while I liked collecting my favorite players, there was a secondary reason I collected baseball cards: the idea that what I owned were not just trading cards, but an investment. Old baseball cards were going for astronomical amounts at that time, so it only made sense to my childhood brain that new cards eventually would, too. Price guides tracked fluctuations. Comics featured in some of this speculation, too, but at least I also enjoyed the stories.

This meant that I was usually more excited about getting valuable cards than I was about getting my favorite players. My own favorite baseball player as a kid was Frank Thomas, which I think I selected because he was both a good player and also (at the time I decided this) relatively attainable on the secondary market, price-wise. And I figured if he got better, those prices would go up. What a little capitalist!

You no doubt know what happened from there: The baseball card market became oversaturated and collapsed by the mid-1990s. Certain cards were faked. Professional graders became middlemen whose imprimatur was required to sell cards at any value. Kids like me moved on, while younger kids’ card habits moved toward Magic: The Gathering and Pokemon. Frank Thomas became a star and made the Hall of Fame, and his rookie cards still aren't worth very much. There were just too many of them out there, and too many kids like me who kept them.

Cards stayed around after that bubble burst, and the industry has even been in a bit of a boom recently. There have been some eye-popping sales of certain cards. The market is less saturated and more carefully run; companies manage supply more responsibly now. Pack-opening videos make for popular streams.

But core problems of the industry persist as they do with any physical item. Things that exist can be faked or altered; they are vulnerable and tend to degrade. In 2013, former auction house exec Bill Mastro admitted to doctoring one of the most famous baseball cards in history, the T206 Honus Wagner. That card, which sold for $2.8 million to Arizona Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick, is legendary for its quality. Now we know one reason why.

This is where the idea of digital collectibles comes in. These digital items exist on the blockchain, and by design cannot be altered or destroyed. This idea was first implemented with Crypto Punks. A company named Larva Labs created the idea of an NFT, a non-fungible token—a cryptographic token that is unique and not interchangeable with any other. Each bitcoin is worth the same, but each Crypto Punk was unique. That inspired a standard for NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain.

Crypto Punks proved pretty successful, and the idea was eye-opening. It wasn't hard to see that if you could create something truly collectible on the blockchain, you could also make a massive market without the slack or fees or attrition of physical collectibles. “NFTs are beautiful,” says Zack Seward, managing editor of the business desk of Coindesk, “in that they are as irrationally human as any other niche collectible.”

Or irrationally feline. A company called Axiom Zen launched CryptoKitties in 2017. That game allowed players to collect unique cats and breed them, creating more unique cats. There was also a marketplace, with the company taking a cut. People enjoyed it, and spent a ton of money buying digital cats; one sold for $140,000. The game became so popular that it slowed the Ethereum network to a crawl; this meant that the game also became too expensive to play because the “gas” (the price to complete transactions) became too high. The game subsequently became less popular. The value of the digital cats plummeted. People moved on.

Axiom Zen did not. The company’s Dapper Labs division raised more money and created a new blockchain, Flow, that solves that overloading problem. In the summer of 2019, the company signed a deal with the NBA.

The product they created was NBA Top Shot. Users buy packs that contain “moments”—everything from a Devin Booker dunk to an Andrew Wiggins layup. Individual moments come in editions, open or closed, and can then be resold, traded, given away, et cetera. NBA Top Shot is basically a website that lets you play a game that resembles a stock market, only it’s about basketball players. Investors get to experience the 1980s and 1990s trading card boom—but online, and faster, and also without having to actually own anything. It is extremely, almost troublingly popular.

Imagine a “perfect” trading card market. There would not be fakes or alterations. Card grading services would not exist or need to exist, as cards would always be in mint condition. A complete list of all transactions relating to a particular card would be available, and sales could take place almost instantly. There would also be a forced and enforceable scarcity of cards, with all buyers and sellers aware of how many cards were printed.

NBA Top Shot has created that market. It's just not for actual cards, but stylized versions of looping basketball highlights. These, of course, are not intrinsically valuable. And while they exist on the blockchain as cryptographic hashes, they are currently only for sale and on display on the NBA Top Shot website. You don't need to own one to watch one. But if you "own" one, you are the only one to own it.

And baseball cards aren't intrinsically valuable either. That famous Honus Wagner card from the American Tobacco T206 set sells for such a high price in part because of the stories behind it. Trading cards are loaded with more than a century of history and lore, as well as the nostalgic value for anyone who once collected cards as kids. Top Shot highlights have none of that, but by aping the familiar shapes of trading cards and other collectibles—each moment is identical but has a different serial number—Dapper Labs convinced themselves that they could convince other people that these things were worth something.

They were right. Top Shot’s closed beta offering drove $2 million in pack sales. A LeBron James dunk in a “Cosmic” edition sold for $5,200. It was at this point that collectible mentality entered the market. Certain serial numbers were worth more than others, with low numbers tending to fetch much higher prices. That forced scarcity caused certain cards to shoot up in value. Certain “insert” cards came with a smaller digital minting, which made them more desirable. And just as card companies came up with checklists in order to encourage kids to collect ’em all, Top Shot features “challenges” that encourage you to collect certain cards in order to unlock even more rare and possibly much more valuable cards. These drive up the prices of certain cards needed to complete challenges. Like any good gambling game, NBA Top Shot subtly (or overtly) encourages its users to spend more money on the platform, with the promise of greater riches ahead.

Jack Settleman, a 24-year-old New York City resident who runs the Snackpack Sports snapchat and podcast, got into the Top Shot beta during the middle of last summer. He says he didn’t get it at first, but eventually began to enjoy buying packs, opening them on the platform and playing around in the marketplace.

“At some point, I just dove into it and it clicked for me,” he says. “Maybe it was confirmation bias. Maybe it was the transaction volume on the site. I finally understood why these things have value. I have some bitcoin. I love the digital space. I love sports cards. This is a perfect blend of that.”

A lot of people started agreeing with Settleman this year. Thousands and thousands of users have flooded Top Shot’s open beta. Packs that once sat on the market are now scooped up almost instantly after they drop. Individual moments have sold for thousands. Settleman bought a LeBron moment for $47,500. Per a site that tracks moment value, Settleman's account is in the top-100 in valuation on the platform—his moments are worth $3,274,375.

I talked to another Top Shot collector whose Top Shot moments are currently worth somewhere around $180,000. He wanted to remain nameless “because things have gotten crazy.” A California resident with a wife and two kids, he is a middle-class dude and was not into crypto or digital collectibles or anything else in that space. He was not even really all that into basketball. But in early January of this year he learned of Top Shot and started buying packs, then buying and selling on the marketplace. His initial $700 investment has left him with thousands in his account and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of moments.

He wasn't really able to explain what fully drew him to the platform besides the ability to make money. “It just looked interesting, watching videos of people opening the packs," he said. "It was collecting cards, but online, and then you resell them on a marketplace—it was just a whole new thing that I just wanted to do and just see where it goes."

Despite how silly I find it retrospectively, I enjoyed collecting cards as a kid. The cards can be fun to collect on their own. But the idea of opening a pack and getting rich, through some kind of complicated lottery in which you are stuck with small photos of Danny Jackson and Bobby Estalella if you lose, can turn it from hobby into obsession. The mental impulse at play is elemental and very much not just something for kids. Top Shot slides gracefully into a space between that instinct and a market built to exploit it. Do you find Robinhood and other stock-buying apps too complicated? Would you understand or appreciate it more if it were about basketball players?

This is where I entered. The other people in my sneakerhead group chat are young and online; I am pretty sure that, at 38, I am the oldest. Everyone is familiar with or involved in reselling. Top Shot came up. People thought it might be fun, or at least a fun way to make money.

On a pack drop on February 4, I purchased three packs. I opened two and got six moments. None seemed all that impressive to me, with the possible exception of an and-one jumper from my favorite player, Joel Embiid. None were all that valuable on the secondary market, either; the price for the moments I got was about $3. I got two moments from my most hated team, the Celtics. I quickly jettisoned my Marcus Smart moment for $2. I just wanted it out of my collection.

I stewed over having spent $30 on whatever that was more than once over the next week. But when my buddies alerted me to another pack drop, I bought a pack of “Cool Cats” moments. This time I pulled an incredible pack: A Steph Curry assist, a LeBron James triple—the cool one from earlier this year against the Rockets, with the no-look celebration—and a Tyler Herro “Cool Cats” card. My Curry and James serials were pretty low, I thought, and so I priced them at high valuations, around where similar serials were priced. I threw a few more cards up for sale at what I thought were high numbers. Then I forgot about Top Shot again.

When I logged in to Top Shot a few days later I saw that I'd gotten a Gordon Hayward moment off my books for $25. My Curry moment had sold for $79. My James moment sold for a seemingly-astronomical $969. I wasn’t sure what to do except put my Herro moment up for sale for $769, along with a few others at more reasonable prices. They all sold. Suddenly I had more than $1,800 in my Dapper account.

And it turns out I didn't sell even close to the top of the market. Whoever bought my LeBron moment has since sold it for $1,985. Top Shot has now done more than $230 million in sales, with more than $200 million coming in the last 30 days.

In my exuberance with my newfound riches, I bought a $149 Ben Simmons dunk. What caused me to spend $149 on a highlight I don't care about from a player I don't even really like? I will be honest: It was that the money seemed fake.

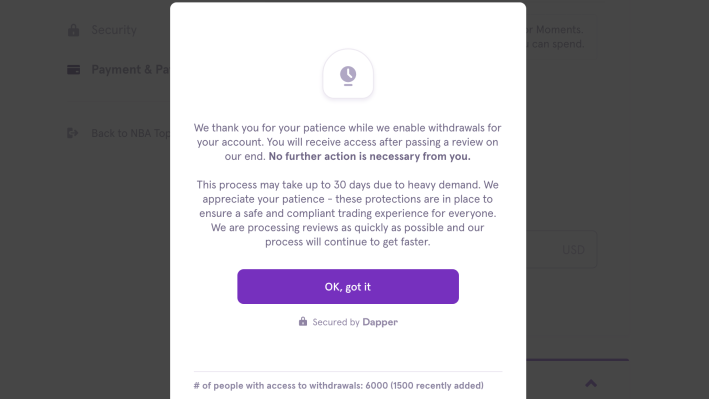

The current NBA Top Shot setup makes it seem faker. My balance on Dapper, the wallet that NBA Top Shot uses, is $1,718.70, but I cannot withdraw it. Only 6,000 users on the platform can, according to Dapper.

Dapper says this is a result of the platform’s growth over the last few weeks. In their Discord, a Dapper Labs employee says the problem is customers were being approved to withdraw on a manual basis, and that once things were automated the system would be better. This did not inspire confidence in me.

But I did find someone who was able to cash out. Josh Ong, a 37-year-old communications consultant in New York, was already familiar with NFT and had purchased some CryptoKitties years ago; “they’re probably worthless now,” he said, correctly. But the idea of a crypto-collectible with an NBA license intrigued him. He spent about $250 on packs late last summer.

By January, the moments he pulled from packs were selling for around $5,000 in total on the platform. He got into it at that point, and bought more cards. He bought and sold moments on the marketplace. He participated in challenges. Eventually, he gained the ability to withdraw and took out about $3,000. It hasn't hit his bank account yet, though.

Ong does expect the money to get there. But the current problems with Top Shot—the lack of withdraws for most users, the current inability for new users to register—weren't a great sign. “Dapper already has in its company history, with CryptoKitties, the trauma of success actually crippling a product,” he said. They have ostensibly figured out how to solve that problem with a new blockchain, but now new problems have arisen. This is the second crypto-collectible released by this company that has been swamped when it tries to scale.

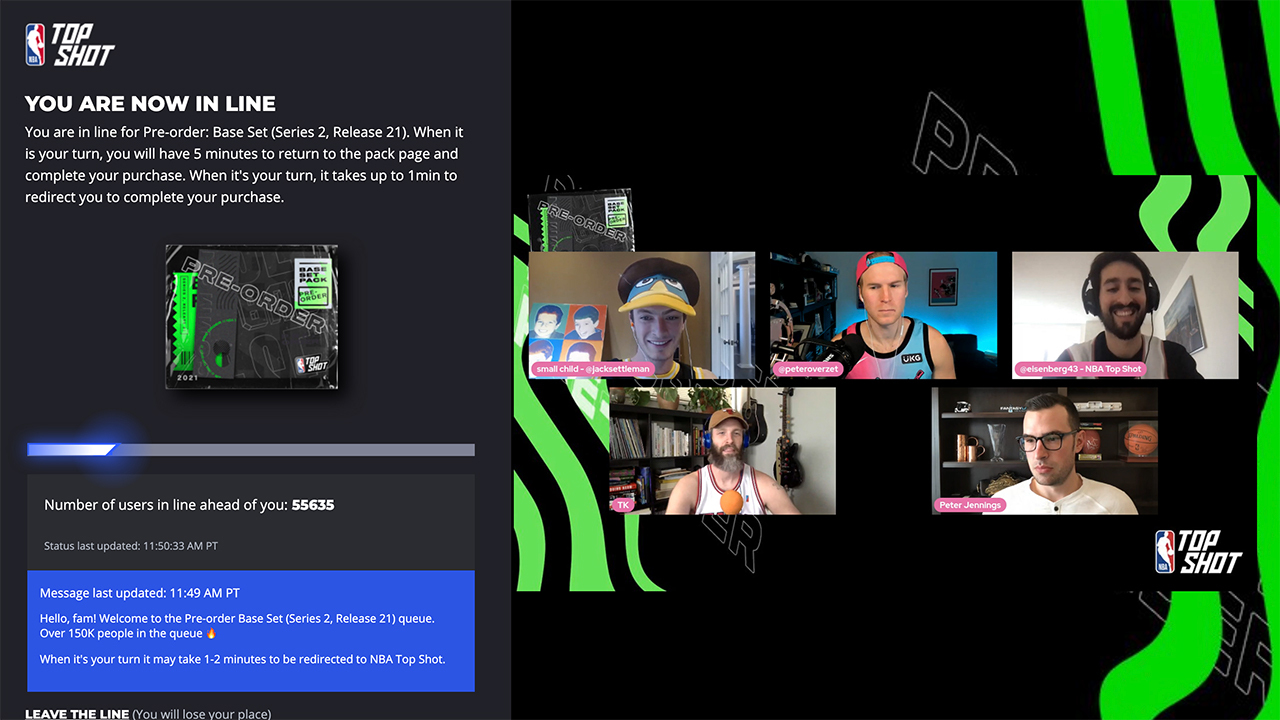

Much of the Top Shot experience is pretty bad, currently. Most users can’t withdraw money. New accounts can’t sign up. The marketplace is frequently down for maintenance. A pre-order queue on Saturday took hours; I went out, got lunch, ate it, and returned to my computer to find that I was still tens of thousands of people away from getting to make my purchase. I got that $9 pack eventually. But was it fun? Would I have done it if not for this story? What the fuck was I doing?

There is one obvious and much bigger question, which is how could these stupid things actually be worth this much? If I was going to believe it, I would need to talk to some crypto evangelists. I found them in Priyanka Desai and Derek Edward Schloss. The two are members of FlamingoDAO, a non-profit decentralized autonomous organization that invests in non-fungible tokens. In January, FlamingoDAO purchased a CryptoPunk for 605 in Ethereum—which, at the time, was worth $761,888.57. Desai and Schloss are both investors, and both are into crypto. They both also have law degrees. I wanted to know how they could possibly think this CryptoPunk was a good store of value.

I guess they convinced me. CryptoPunks invented the idea of the NFT collectible. If this kind of thing takes off, these are the first. (Imagine owning the first painting!) There are only nine of these particular alien CryptoPunks in existence, and one hadn’t been on the market in a long time. “Many of the members of Flamingo would say that they see CryptoPunks as almost like the Warhols, or what have you, of NFT collectibles,” Desai says. “They're OG. They look pretty cool. You're seeing that now. A lot of the Silicon Valley people are edging into that, and making it their avatars on Twitter.”

Schloss was bullish on Top Shot as well; he has been managing FlamingoDAO's investment on the platform. “For NBA fans now … their only outlet isn't just watching the game or going to a game, it's now owning relics that are related to the game,” he says. “That to me is a massive total addressable market, and we're only at 30,000 daily users of Top Shot.” He also envisioned different “perks” that owners of certain moments could get, perhaps while they attend a game. There is more gamification ahead, too. In a weekly fantasy basketball game called Swyysh, players on certain moments compete against each other based on what happens in that week’s games. If you assume all of this is going to work, it seems like Top Shot really is going to be huge, and in a way that might actually make people some money.

If I'm a convert in any sense, it's that I actually think the tech is kind of cool. The highlights really are neat-looking, and the idea of getting random moments from pack drops is a fun type of gambling, I suppose. The marketplace is low-friction and it solves a lot of the problems of the secondary market in trading cards. None of what seems ridiculous about it is evident when you're actually in it. But the more I thought about NBA Top Shot and crypto collectibles, the more it depressed me.

The main issue is that there’s no there there, at least for me. The moments are just little highlights. Most people I talked to who are involved in Top Shot are not all that excited about the actual moments they own, or "own." They’re very excited about the possibility of getting in early and making a lot of money from it. They're also excited about the possibility of future uses of NFT tech, all of which can more or less be summed up as To Make Money From It. They're excited about the future uses for each Top Shot moment. But right now, with the product's expansion, the market is a mess.

“You look at a card market, you have hobbyists, kids, collectors, whales, investors, resellers, scalpers,” Ong says. “You need to manage a market that has room at the top and the bottom. The floor moved up so fast that regular collectors are priced out. So now it's a market that's only full of sharks and whales and people who are there for the money, and maybe some random people who got in."

It always seems so easy. Get in on the ground floor of a new product, invest a little, outsmart other people, and then get rich. You coulda been a Bitcoin millionaire. You coulda been in on the ground floor of Ethereum. How'd you miss out on GameStop stock? But never mind that: Here on NBA Top Shot, you could turn $700 into $200,000 in digital moments—and maybe one day you'll even be able to withdraw that money, too. Then you can retire at 40.

I think I'm done chasing it, though. I’ll keep my Embiid and Simmons moments, and I'll withdraw the money in my account if I’m ever able to do so. But with the one other moment I have left, I’m shooting for the moon: If you want this Kelly Oubre Jr. dunk I still have for some reason, it will cost you $101,000. I am prepared to reassess. Make me an offer.