In the summer after my first year of college, I interned at an art museum in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. I was the social media intern—an unpaid position I'd gotten because I had declared in my cover letter that the app Vine was the future of social media and also because few others applied. I admittedly wasn't as interested in art or social media as much as I was interested in the abstract idea of having an internship, and so I spent many of my lunch breaks walking to the science museum that sat on the opposite end of the plaza in the park. The museum held a planetarium, towering tanks of sea creatures and a butterfly dome, all of which I thought I'd much rather witness than art.

Still, I dutifully Vined, a job that largely consisted of me wandering around the museum to find art I wanted to Vine about, as well as fill my quota of Vines celebrating the abstract expressionist Richard Diebenkorn, whose work was featured in a special exhibit. No matter how much I Vined Diebenkorn's landscapes—meaning the irregular, abstract colorblocked paintings I was informed were landscapes—I did not find any pleasure or understanding from his art. All my favorite pieces in the museum were sculptures, perhaps because although art remained the same every day, the shadows they cast changed with the sun and your position in the room, which gave me the impression that there were infinite perspectives from which to see the art, of which I was just scraping the surface.

All the best shadows came from the wire sculptures hanging in the elevator lobby. They dripped from the ceiling like candle wax, all crocheted in a woven mesh like chain mail. Some oozed like strands of droplets, others nested into each other like stacks of hats, and others dangled alone like chandeliers. These last sculptures always reminded me of radiolaria, the microscopic organisms with intricate and crystalline shells. All were hung close to the wall to cast their shadows directly behind, sometimes bleeding into the shadow of another sculpture or cast again as a gauzier shadow on a more distant wall. (Incidentally, this quality made them perfect for Vines, which captured the way the shadows waxed and waned and dribbled into the light.) Walking amid the pieces made me feel like some planktonic creature, skimming the surface of the ocean and dodging the predatory radiolaria and their prickly glass skeletons. I passed them each time I entered and left the office, and it always felt odd to me that the sculptures were tucked away in this liminal gray elevator bank and not placed centrally in a bright white exhibition hall where people felt inclined to look and linger, not merely pass through.

These 15 sculptures were all by the Japanese-American sculptor Ruth Asawa, who was born in Los Angeles and lived most of her life in San Francisco. Asawa drew among other artists while she and her family were forcibly incarcerated in various Japanese internment camps during World War II. She spent 18 months in the camps and eventually joined an artistic community at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where she would begin weaving the wire sculptures that earned her renown. In my third month at the museum, I read in the local paper that Asawa had died at the age of 87, and I found myself standing vigil by her sculptures as the metal elevator swallowed and spit out visitors who seemed entirely oblivious to her death, and perhaps even her sculptures. It was a bit hypocritical, as I had no idea Asawa had been alive, and yet I felt a profound sadness that the sculptures remained by the elevator without even a bench on which people could sit and look at her art. (I learned in writing this that the 15 hanging sculptures Asawa donated to the museum are displayed in the elevator lobby because there is no charge for visitors there—honoring Asawa's belief that art should be accessible to all.)

The next week, my internship ended.

On Monday, I went to see "Ruth Asawa Through Line," an exhibition running through Jan. 15 at The Whitney. The exhibit features only one of Asawa's dangling wire gourds. Rather, the show is focused on Asawa's drawing practice, which unlike her experiments with wire sculpture, lasted her entire life. There were drawings she'd made of her sculptures, rendered two-dimensional in meticulously looped ink. There were horizons crafted from Greek meanders—wave-like borders that folded in on themselves, seemingly into infinity. There was a stately gyotaku print of a fish. A watercolor tableau of ebullient persimmons and portraits of bouquets Asawa had received from friends, which functioned as a portrait of the giver, closed out the show.

To my eyes, the stars of the show were four folded paper sculptures framed alongside each other. Asawa had pleated the paper to create a repeating pattern of black and white stripes, which created different shapes as you walked by each piece. One appeared to be black and white stripes if you gazed at it head-on, but quickly morphed to jagged zig-zags if viewed from an angle. The paperfolds seemed to contain its shadows, the black sections warping and vanishing from different vantage points. There seemed to be infinite ways to see the paperfolds.

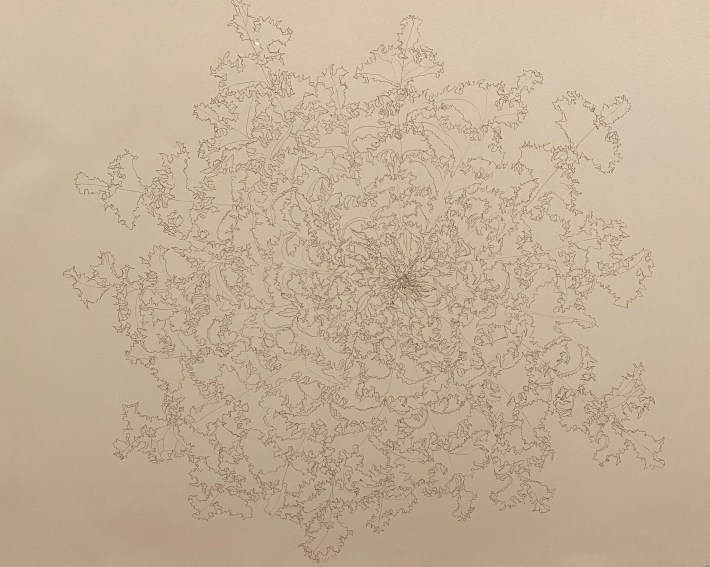

I was stunned to see a single artist's work in so many genres, work that felt both full of play and uninterested in mastery. Yet all the work seemed to suggest that the most precise way of capturing an object and its implications in the world, was often an act of abstraction. I found myself returning to a drawing at the center of an exhibit: Asawa's rapturous rendition of the unfurling leaves of an endive. The endive was sketched from life, a faithful portrait of a single lettuce in a point in time, but the filigreed edges of each leaf turned the vegetable into a vortex. I frequently found myself lost trying to understand what was lettuce and what was the space between its leaves, the spaces that would create its fractal shadow. I found myself dizzy at the thought that a lettuce head would leave me in a state of so much awe and confusion.

In my own writing practice, I often find myself reaching for the sublime in things that already seem to grasp toward it—how a jellyfish can look like water that has come to life or a blind shark navigates the sea for hundreds of years through sound. Asawa's endive, her folded paper, her oyster, and her persimmons, reminded me that the art I often find most transcendent reaches the sublime through the attention and care it pays to the inner lives of the ordinary: a head of frisée, the soft creature inside a clam, a heap of ripe persimmons. The art was not just the endive, but the hours of attention and care Asawa paid to the lettuce, and the understanding that came through that attention. In text accompanying the exhibition, the Whitney quotes Asawa's belief that "art is not a series of techniques, but an approach to learning, to questioning, and to sharing."

As I left the exhibit, I wanted to devote more attention to the ordinary things in my life. I felt a rush of affection for the living and once-living things near my apartment: the desiccated lemon in my fruit bowl, the money tree in my window, my five blazing ember tetras. I can't draw for shit, but I suppose I can contemplate as good as any other. I want to do a better job of rendering the things I write with more care and attention, to find the sacred in the ordinary. I want to be able to capture not just the thing, but also its shadows.