Modern pentathlon is in crisis. Even athletes who compete in the sport say it has been declining in popularity for decades, and when modern pentathlon finally made the news last summer it wasn’t quite the way supporters had hoped.

At the Tokyo Olympic games, coming into the equestrian portion of the five-event contest, a German rider was paired with a horse named Saint Boy who simply didn’t want to cooperate. No matter what the rider did, Saint Boy reared and stalled and refused to jump. The rider reacted by beating the horse with her crop and her coach reached out and punched the animal from the sidelines. The horse is, as Defector has previously reported, innocent, the rider dropped from first to 31st place, and her coach was ejected from the Olympics.

The modern pentathlon may be desperate for relevance and attention, but this was not the kind of press they wanted. And to make things even more complicated, the reaction to this incident has created a rift between the athletes and the sport’s governing body that involves allegations of corruption, pillow fighting, and the potential death of the sport.

The Saint Boy debacle wasn’t the first time modern pentathlon faced criticism of its riding portion (for reasons we’ll cover in a moment). Calls for reforms have come from athletes and critics alike. “The current system is awful for both athletes and horses,” said Joe Choong, the reigning gold medalist. He gets hate mail about animal welfare most days, and said that he actually agrees with a lot of it. “We do care about horses and totally accept that the sport needs to change.” What he didn’t expect what the precise change that his sport’s governing body actually made.

In November of 2021, the Union Internationale de Pentathlon Moderne (UIPM), decided that the solution to the public relations disaster that was the Saint Boy incident was to replace riding entirely with a completely new fifth discipline. The move shocked many competitors, as did the exhaustive list of qualifications the UIPM hoped to see from the replacement event. The new sport, according to their thirteen-point-long list, must not already be governed by any IOC recognized federation, must be global, fun to watch on TV, easy to transport, cheap to set up, feature skills the athletes already have, have minimal injury risk and “follow the Coubertin narrative of the most complete athlete,” among other demands.

This list immediately eliminates some of the most obvious replacements: equestrian show jumping (with a horse the rider actually knows), cycling, karate, ski mountaineering, cricket, bowling, rock climbing, polo, tug of war, water skiing, racquetball and more are all out as they are technically governed by an IOC-recognized International Federation. Other sports fail on the affordability angle (airplane racing) or don’t have anything to do with the skills that modern pentathletes currently train (bowling).

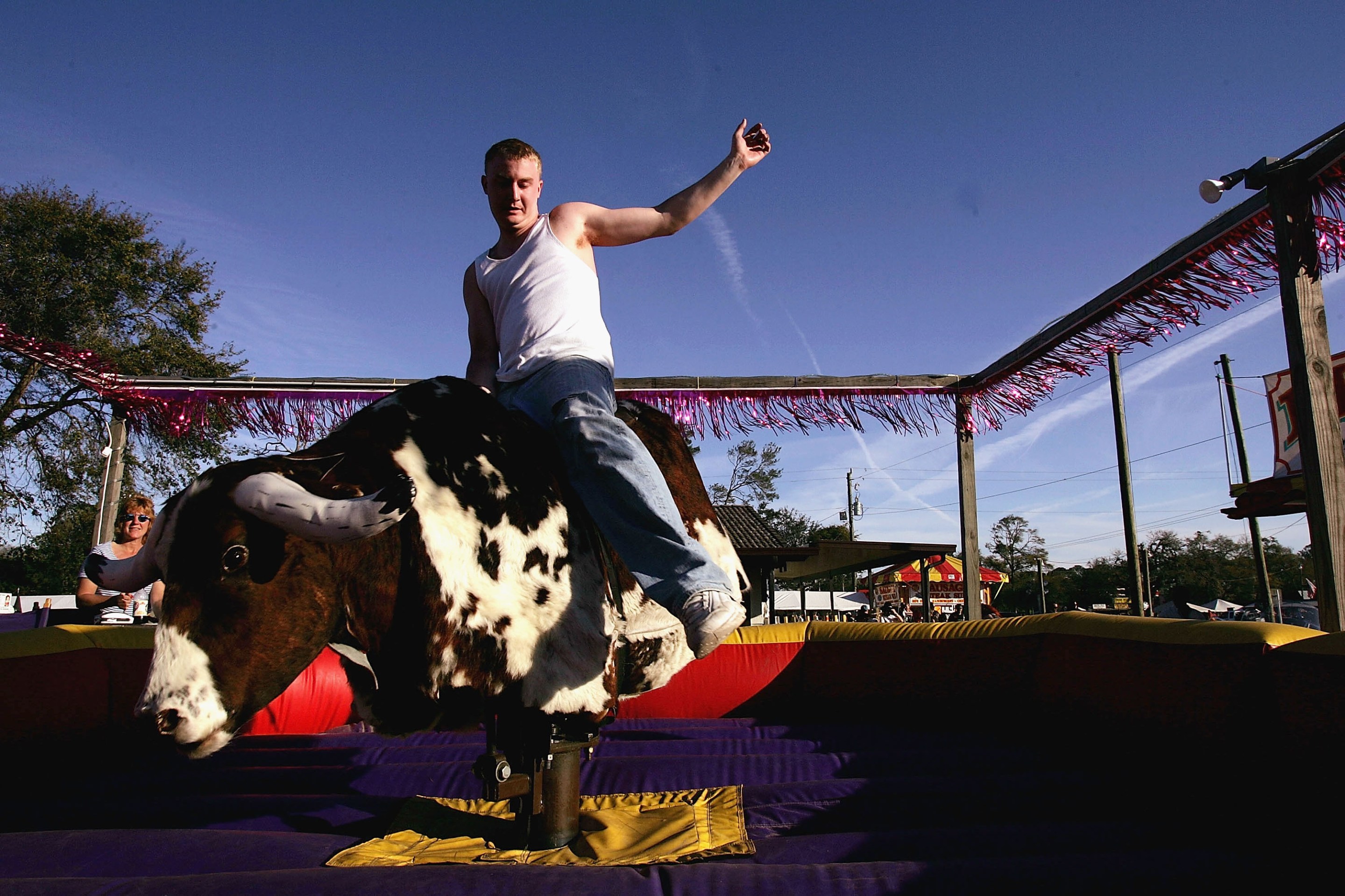

Given this exhaustive wish list, what sports could even qualify? The UIPM recently announced some of the candidates it is considering within its working group — which included motorcross, drone racing, roller-skating, obstacle course racing and "traditional Gambian pillow fighting," which may or may not be a real thing. But if there is one thing the UIPM has stressed in all their communications about transforming this sport it’s the need to keep an open mind. In that spirit, I would like to offer up my completely unsolicited opinion and present them with another choice: mechanical bull riding. And, once I explained to George Chicha, organizer of the Mechanical Bull Riders World Championships, what modern pentathlon was, he agreed. “Oh yeah, just give me 30 days notice and we’ll be there,” he said.

To illustrate why I think this is more than just a joke, it’s worth backing up to explain the premise of the modern pentathlon — a sport that even its athletes admit most people have likely never heard of. Invented by the self proclaimed “father of the modern Olympics,” Pierre de Coubertin, the modern pentathlon is a uniquely narrative contest. Each of the five events represent one of the skills that a cavalry soldier might have to possess if he were caught behind enemy lines and wanted to survive: fight off his enemies (fencing and shooting), evading them (swimming and running), and stealing a horse to make his escape (show jumping). Because of this narrative, the equestrial portion of the sport is unusual: Instead of riding a horse they know, competitors are paired up with a random horse they meet just minutes before having to mount and take that horse along a show jumping course. The horse is supposed to be stolen, after all.

And it’s this relationship with horses that has put modern pentathlon in the crosshairs of animal rights activists for decades. At the 2014 World Cup, for example, athletes noticed that the horses they were being given were poorly trained and cared for, with swollen legs and open wounds. “We protested as athletes that you need to treat these animals better,” said Samantha Schultz, six time U.S. National Champion in the modern pentathlon. She pointed out that not every country has the resources to train their athletes in equestrian to a high level, which makes the random pairing even more challenging for those riders.

Not only do the riders have no relationship with the horses they ride, the sport is also entirely based on time. If a horse falls, or a rider falls off, there is no stopping to check on the health of either party. Every second counts, so riders leap back into the saddle as quickly as they can and continue on. And, of course, a disconnect between horse and rider can lead to incidents like the one we saw in Tokyo.

The exact reason why the UIPM completely nixed equestrian is still murky. Some athletes I spoke with told me they heard that the IOC demanded it behind closed doors. The UIPM vice president said that it was “to erase our reputation as a sport for high society and the elite - before it is too late." No matter the logic, the announcement came as a shock to many. Choong read the news in an article online, and said that at first he thought it was a joke. “You wouldn’t go and change the 100m running event to swimming,” he said, “how can you change our sport into something completely different?” Many people had assumed the UIPM would make changes to the equestrian portion, tweaks that would ensure rider safety like practice rides with your assigned horse. To replace the discipline entirely wasn’t even on his radar, Choong told me. Schultz echoed that dismay and surprise. “We knew there were issues with riding, but we had never heard that riding was going to be completely taken out,” she told me.

The athletes I spoke with had no real suggestions for what should replace riding. Both Choong and Schultz think it should stay, with changes. But the UIPM is soldiering on, looking for a new fifth discipline that fits its long list of qualifications. So far, nobody in the sport that I spoke with had even considered replacing the horses with robots — which is essentially what mechanical bull riding is. But if the story of modern pentathlon is one of a soldier, it’s far more likely that a modern officer would encounter an animal-like robot they have to conquer, than an actual horse. So to find out if my idea had legs, I called a guy named George Chicha.

Chicha had never heard of modern pentathlon before I called him. He’s in his seventies now, and has spent the last several years trying to make his own sport a success, organizing Mechanical Bull Riders World Championship events around the United States. He has strong opinions about which mechanical bulls are the best (A&P Mechanical Bulls, with a real bull head attached to the front of them) and is proud that his sport tends to favor women (“women are just tougher,” he tells me). The first ever Mechanical Bull Riders World Champion was an equestrian coach named Laura Moore who beat out a professional bull rider by five whole seconds.

When I read the UIPM wish list to him, George rattled off why he felt bull riding could satisfy each and every one. “Allow for global accessibility and universality?” You bet, he said. While bull riding is currently a very American sport, he said he’d gotten emails from all over the world when he first started doing events, asking him to bring bull riding to Australia, Brazil, Canada and more. (Those plans have been stymied by COVID, but he hopes to get back to them soon.) Mechanical bulls could fit neatly in the stadium, are easy to transport and low energy to operate, and are far less expensive than living horses. Chicha did the first world championship event for a cool $800.

Even that nebulous idea of “the Coubertin narrative of the most complete athlete” connected with Chicha. Last year he took out a half page advertisement in The Wrangler, a magazine dedicated to horse and rodeo news, advertising their bull riding championships. A big red banner spans across the ad, which reads “THE ULTIMATE ATHLETIC CHALLENGE.” “It is the ultimate, because you not only got to have balance, but you got to have agility, especially when the bull changes direction,” Chicha said. “You got to have courage, you got to be fit, you got to have focus.”

And as far as entertainment value? “It’s all about the show!” he said, excitedly. “You get the bull and you get the lights and you get the music and you make it work, and it's the show!”

Following repeated requests for an interview, the UIPM responded with an email saying: "You can find detailed and updated information about the New 5th Discipline selection process on this page.” I still have no idea how they might react to the idea of adding mechanical bull riding to the modern pentathlon. But when I asked Choong and Schultz for their thoughts, they both just laughed. “That would be hilarious,” Schutlz said. “I think it’s just as plausible as the pillow fight idea,” said Choong. “I think you can say anything and they'll pretend they're considering it.”

When I pressed them, presenting the arguments Chicha had made, and reminding him that it was basically like replacing the horses with robots, it seemed like neither could tell if I was joking or not. “I don't know enough about it, to be honest,” said Choong. “My thing would be no, but that's because I'm so set on horse riding, right?” Schultz echoed his sentiment. “I think it would kind of make our sport look like a joke, to be purely honest,” she said. “Although it would be quite entertaining, which would fit into how things are seeming to go with the Olympics.”

This is a position shared by a lot of his fellow athletes. When polled by the UIPM Athletes Committee, 75.8 percent of athletes who responded wanted to keep the equestrian portion in some way. Since the UIPM’s announcement, over 800 athletes have signed their name to a letter asking the organization to reconsider its decision. Choong has been one of the most vocal about his protests. While other athletes have to be careful what they say, and how much they push back against their own governing bodies, Choong has a bit of immunity. “It's very difficult to find a good reason to stop the Olympic champion from competing in his sport without causing a massive scene.”

Choong’s theory is that the UIPM has already secretly picked the fifth discipline, and is simply trying to back its way into the decision. He pointed me to the fact that one of the people who serves on UIPM boards, Rob Stull, is also involved in the leadership of World Obstacle. (Since that rumor surfaced in December, the website for World Obstacle has removed its page detailing its board members.) Stull has not responded to my emails asking if he has a conflict of interest, but the UIPM has said in their newsletter and social media pages that it has not yet made any kind of decision.

Choong has been spearheading a group of modern pentathletes trying to work against this change, but it’s unclear how the UIPM will respond. They want the old leadership to step aside, and bring in new blood. (Choong points out that the current UIPM president has had the title longer than Choong has been alive.) And ultimately they want equestrian to return under new rules that are better for animal welfare and athlete safety. “I almost feel that if they take the horseback riding out and add something else in, I would almost rather not have it in the Olympics at all,” says Schultz. “It's not the same sport.”

As for Chicha, he isn’t holding his breath for a call from the UIPM. But he does think that mechanical bull riding has a future as a sport. “ESPN needs to come in and cover this thing. If they can cover cornhole, they can cover mechanical bull riding.”

And while I had fun proposing mechanical bull riding as a potential replacement event, for those who compete in modern pentathlon, this is a true existential crisis. Modern pentathlon was not included in the initial program for the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028. If the UIPM can’t find something that satisfies the IOC, they may be left off the Olympic roster for good, which could mean an end to the sport entirely. “The current leadership has never managed to find any sponsors to make it a sort of sustainable sport outside of the Olympics,” Choong said. “If we don’t get accepted into LA or after that, the sport is finished.”

Schultz agreed. She recently got her Olympic ring from being in Tokyo. It has a horse on it, with five dots, representing each of the five disciplines. When the ring came in the mail, her mother pointed out that the ring could be one of the most rare artifacts around. Women were only included in the modern pentathlon in 2000, and now the sport is changing drastically and perhaps on the brink of extinction. “It breaks my heart,” Schultz said.