Nobody thinks of Luke Voit as a home run king, and nobody thinks of Shane Bieber as someone who won pitching's triple crown. The truncated 2020 MLB season really did happen, but like so much else that happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, the general public has mostly decided they’d rather not think about it. The way this works in baseball is that three-year statistical averages use 2019, opting to fold in the past three full seasons instead of the abbreviated pandemic campaign. Generations from now, photos of cardboard Lefty Grove in the Oakland Coliseum stands watching a baseball game next to stuffed teddy bears and elephants will be greeted with the same shock and confusion that people today bring to finding out that chloroform and morphine were used as cold medicine in the 19th century. Damn, the historical record will ask everyone who remembers that moment, you lived like this?

But for 29 guys, that objectively real fever dream of a season was their only taste of the major leagues. It’s reasonable, in retrospect, for fans to want to forget those months of piped-in cheers echoing through empty ballparks, but doing so has also cast these players, all of whose careers began and some of which ended during that season, into history’s dustbin. “My life pretty much consisted of just being in the hotel, going to the empty stadium, doing our thing, and going right back to the hotel,” said Elliot Soto, one of those 29. Soto is now in Triple-A with the Twins. Shortened, desolate, and eerie, Soto’s career and those like it count just as much as each of the nearly 23,000 others in major league history, even if there was never a paying fan in the stands to see any of it happen.

A big-league debut is, by the cruel odds of the sport, the happiest of implausibilities, and the culmination of a life’s work. Family members are there, and the moment itself is usually enough to get a courtesy round of applause even from fans of the other team. “The first thing you think is, cost be damned, how do I get my family to the game,” the former MLB reliever Andrew Miller told me. “But being in the stands wasn’t an option, and neither was hugging mom and dad at the hotel.” The hard boundaries of the pandemic guidelines left players no choice but to improvise.

“My dad wasn’t able to come up, but my mom was,” said Rockies minor leaguer Ben Braymer, who made three outings with the Nationals that year. “I pulled over on the side of the road, got my mom a plane ticket to D.C., and had her book a room at a hotel across the street from Nats Park with a rooftop bar. Sure, the players looked like ants and I didn’t pitch, but my mom was able to watch every game.”

In most cases, stadium placement wasn’t as convenient and families had to watch from afar. Soto, who was a 10-year minor-league veteran when 2020 got off to its belated start, played three games for the Angels that September. He recorded two hits in his second game; when it was over, he received a video that he has kept to this day. His wife and in-laws had recorded their live reaction to his first at-bat and his first hit. “It’s a different memory for a first hit,” Soto told me prior to a St. Paul Saints game. “I still love it, though. It’s my favorite video.”

For Soto, starting his first major-league game was so similar to games played at the alternate site, and so separate from the baseball he spent a decade playing professionally, that he almost forgot he was promoted. “I'm just playing nice and loose and then all of a sudden like the fourth inning I'm on defense just standing out there and I'm like ‘Oh, I’m playing the big leagues right now,’” Soto said. “My mind was like it was an alternate site game. I’m next to the same players and there still aren't any fans, I’ve been doing this all year.”

Dakota Bacus, a veteran of eight minor-league seasons, found himself in a similar frame of mind as he made his debut with family and friends watching back home at a local restaurant. “Playing for 10 years, I almost completely forgot about fans, as cliché as it sounds,” Bacus told me from his home in Illinois, where he’s now a pitching coordinator. “I lost those thoughts and nervous jitters a long time ago.”

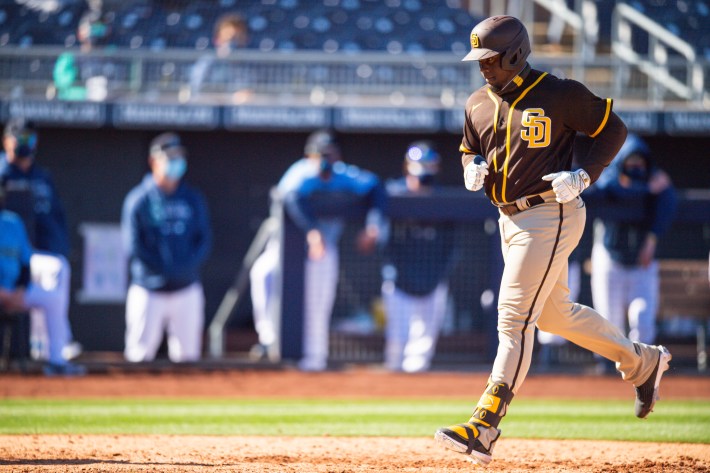

Already living and playing during a season of unprecedented isolation, players with family outside the United States found themselves experiencing an even deeper level of solitude. Jorge Oña made his major-league debut with the Padres in September 2020. Getting his family to his first game was never going to be easy, but the circumstances made it extraordinarily challenging for them to even see it from home. “They were watching my games online, even though it was very difficult,” Oña said through a translator. “Internet access [in Cuba] is difficult to come by and to pay for, because it was very expensive.”

“My daughter was born during the season and I wasn’t able to go see her,” said Johan Quezada, who pitched three innings over three games with the Marlins that year. “If I went back home with two quarantines, I would’ve missed most of the season.” Marlins games weren’t carried on television in the Dominican Republic, so Quezada’s family wasn’t able to see his debut live on a screen, either. His daughter, who was born mid-summer, was finally able to meet her dad following the Marlins’ Division Series loss.

“How many times do you see the young guy walk over to the side of the dugout and hug his girlfriend, his toddler, his parents, or whoever it is and take a picture with them?” Andrew Miller asked. He’d done all that and more over a big-league career that spanned 16 seasons and included a couple of All-Star nods and an ALCS MVP award. He was there for the purgatorial 2020 campaign, too. “And [then] those moments didn't exist, there are countless little things that couldn’t happen. It’s heartbreaking.”

So far this year, two players who were on the original 29 of 2020 Guys made their re-debuts under better circumstances. On May 2, Johan Quezada returned to the mound in Miami, this time with fans in the stands and actual cheers. And Rob Kaminsky, a 2020 Cardinal and current Mariners minor leaguer, took his second turn on that same mound, this time in front of a sold-out crowd as a member of Team Israel during the WBC. Unlike his first debut, this game didn’t count towards Kaminsky's major league career; also unlike his MLB debut, it felt like a big-league debut. “The World Baseball Classic was the big leagues for me.” Kaminsky said. “I’m on a big-league mound pitching to All-Stars in front of 30-40,000 fans, and my whole family was in the stands,” he said. ”That definitely scratched that itch.”

But for other players who have lived their lives in pursuit of scratching that particular itch, being a part of the 2020 season fell far short. “As veterans, we tried to embrace those young guys as much as we could,” said Sean Doolittle, an 11-year big-league vet and 2020 Washington National. “Even with the changes and added difficulty, at the end of the day, those are still big leaguers.” Doolittle’s Nationals opened the season hoisting their World Series flag in front of what should have been a raucous crowd. Instead, with piped-in cheers not perfected yet, Doolittle and his teammates watched the flag make its way up the pole in silence.

In some cases, all that familiarity started to feel more familial. “Especially on that Nats team with a lot of veterans, it almost felt like us young guys were family,” Ben Braymer told me. “I don't want to say I got [my teammates'] undivided attention, but realistically I probably got to experience more of them and their personality than I would’ve in any other season. There was a feeling that if we don't embrace each other, it's gonna be a lot worse than it should be.”

With restaurants closed for inside dining and players restricted to their hotels, the traditional rookie-veteran dinners were rendered impossible, at least in their pre-pandemic form. “We were doing a fantasy draft in Chicago and Paul Goldschmidt ordered dinner for the entire team from a five-star steakhouse,” Kaminsky remembered. “Another night, Adam Wainwright did the same thing. Their options were limited, but they tried to make it as special for us as possible.”

Getting the food sent to the hotel was comparatively easy, but enjoying it over drinks and sitting at a table with teammates was another big-league tradition that was suddenly and strikingly out of the question. At least physically. “Guys got creative,” Doolittle remembered. “[They] would bring their PlayStation or Xbox and talk to each other over their headsets. Even though they were all spaced out, it was almost as if they were hanging out.”

“Playing video games was the big thing to do that year.” Quezada said of his Marlins, who went a week and a half between games at one point after a clubhouse outbreak. “There really wasn’t any other way to interact at times.” Some 2,200 miles away, in San Diego, Jorge Oña had a similar experience. “I just spent my time in the hotel playing video games most of the time,” he said, “since we couldn’t really leave.”

“It felt like a big dorm, basically.” said Elliot Soto, one of several players to make that comparison during our chats. Teams without outbreaks like those that the Cardinals and Marlins endured were afforded more freedom to interact with teammates away from the field. As long as you weren’t stupid and kept it safe, players eventually could manage some semblance of normalcy before and after games. “It was a lot of playing cards, a lot of video games,” Braymer said. “And a lot of pizza delivery.”

“The only time you really felt like you were in the big leagues was outside the stadium,” Dakota Bacus recalled. Even if they had to eat alone, eating the best food in the best rooms at the best hotels still felt like big-league stuff. But suiting up for a game in a makeshift concourse locker room, and then playing in empty ballparks, reminded everyone—veterans and first-timers alike—where they were. What if a lifelong, life-defining dream turned out to feel like limbo?

One thing that the players of 2020 experienced that nobody before or since has is the freedom that comes with having a stadium to themselves. In a normal year, players never sit in the stands. They never have the ability to walk the concourses as they please, even, and they certainly never get to watch the game from a different section every inning. But with stadiums open only to players and team staff, all of these suddenly became daily occurrences.

Fenway Park was built over 110 years ago and on its best days isn’t exactly roomy for fans or the players. When paying customers no longer existed and the players needed to keep safe distances apart, the stadium became the world’s largest clubhouse. “We watched the games from the seats behind the bullpen.” Quezada said. “It was a pretty nice view, too. People pay good money for them.” Before and after the games, players had lockers set up in suites, closets, and in Sean Doolittle’s case, right up against an agonizingly empty hot dog and pretzel stand.

As fun as it was to turn a stadium on the National Registry of Historical Places into a hangout, players told me that the specter of the pandemic was never too far away. “A bunch of us were sitting on the bench and, without thinking, some of our masks went below our nose.” Bacus told me. “Suddenly, one of the security guards crawled over the top of the bench, poked his head down and said ‘HEY, you gotta get those masks on!’” One National nearly screamed in fear at the warning from above, but the players complied and went back to their conversation.

On that same road trip, Braymer made his debut on Fenway’s mound and listened to the echoes off the Green Monster as one of Boston’s most beloved traditions became an unnatural reminder of the wary world outside. “I came in right when ‘Sweet Caroline’ is usually playing and thousands of fans are screaming ‘bum-bum-bum’ as loud as they can,” he said. “Right then it was just me, the song, and nobody else. I almost wish there was someone there to curse at me after I struck out my first batter.”

The Angels' first trip of the season took them to the Now Unsponsored Oakland Coliseum. As a member of the taxi squad not participating in the ongoing games, Elliot Soto found a once-in-a-lifetime way to pass the time. “I thought it would be cool to spend each inning in a different spot,” he remembered. “I’d sit in the first row and then I’d move to the second deck, then the third, then I went out to the centerfield bleachers.” Every one was, more or less by default, the best seat in the house.

Nearly one thousand days have come and gone in the years since the 2020 MLB regular season came to a close on that Sept. 27. For the 29 members of the 2020 club, those days have been filled with their strange type of work—injuries, attempts to rejoin the big-league roster, retirements, and, naturally, reflections on their big-league careers.

“Whenever I tell somebody my story, that I played 10 years of professional baseball and I got to the big leagues in 2020, you can hear by the way I say it that it doesn't mean as much because of it being in 2020,” said Bacus. He’s the only player of the six that I spoke to who has left the sport. “In reality, it’s still the big leagues, but having played the game, it holds this weird vibe that’s hard to fully explain.”

In the year immediately preceding the COVID season, Bacus was a Triple-A All-Star for the Fresno Grizzlies, but never got the call to the big leagues during the Nationals’ championship season. Following his big-league stint, he competed for a spot in the Nationals bullpen, but was one of the final cuts before the regular season began. Despite good numbers in the Rochester bullpen, he was never given another call. At the end of that campaign, at the age of 30, Bacus decided to retire.

Thinking back to those seasons, Bacus pinpointed what felt so off about his major-league career. “I really feel like I didn’t deserve it like I would have in 2019 or 2021,” he said. “I felt more like a tool that was needed just because of 2020 more than me doing anything to earn that call to the big leagues. I’ve come to terms with it and can say that I’ve pitched in the big leagues. But as far as that holding as much weight as it would in another year? That’s probably going to take a little while.”

As he recalled sharing a clubhouse with Stephen Strasburg and Max Scherzer and wearing Jackie Robinson’s number 42 on a big league field in what he called the biggest moment of his life in baseball, Bacus found some firm reality in his MLB career. “If someone were to tell me making the big leagues in 2020 wasn’t real, I’ll accept that. But as far as saying that about my experiences and the people I was around, I’d fight that for sure.”

All the other players I spoke to over the past few months are still writing their stories’ various ends. Two players, Braymer and Kaminsky, have signed with big-league organizations since being interviewed; Johan Quezada made it all the way back to the majors. With a re-debut still in sight, none of these players were inclined to look back on the 2020 season with a sense of finality. They’ve still got new chapters to write.

“I don’t care how I got there. Spending so much time in the minors, nothing mattered to me as long as I got there,” Soto told me when I asked if being a big-leaguer in 2020 checked all the boxes he’d hoped it would. “I kind of think it fits my story, because mine isn’t one of instant success. It’s a lot of grinding, a lot of adversity, and a lot of uphill battles. It wasn’t going to be a storybook and I wouldn’t want it that way. I want all the bumps and bruises.”

When I spoke with Ben Braymer, he was driving down to North Carolina to suit up for the independent High Point Rockers. They play in the Atlantic League, and as with many teams in that league their roster was stocked with former big-leaguers with various pedigrees. “There’s a part of me that isn’t necessarily pursuing playing again because of 2020, but I want to experience it all again at a normal time and see what that’s like,” he said. “It would almost be like a whole new debut and a new rookie season, if I’m being honest.”

Beyond the obvious lack of friends and family, an integral part of Braymer’s journey came in the form of fans who had followed his career from his selection in the 18th round back in 2016 all the way to Triple-A who never got to see him reach the pinnacle of the sport. “Some of those fans would follow me up the system and I’d recognize them along the way and I thought it would be really cool to see them at Nats Park one day and be like ‘Hey, we did it,’” he told me. “I hope I can still do that, even if it took a few extra years.”

“Whether I debuted with fans or not, I’d want to get back to the big leagues,” Kaminsky said. “But I want to make that call saying ‘I’m going back to the big leagues, I’ll be in Chicago tomorrow and I want all of you there with me.’ I’m thankful I had the World Baseball Classic to give me a bit of a chance to do that, but next time I want to be in a big-league uniform.”

The compressed season didn’t give him time to fully prove himself, but Jorge Oña counts himself among those who look back at 2020 with no regrets lingering. “It would have been great to have fans during my time there,” he told me during a San Antonio Missions homestand. “But that didn’t change that I had seen my dream come true. It didn’t change anything for me.” Still, he allowed, “to feel the atmosphere of having people in the stadium during games—I would have liked to have that experience.”

“It wasn’t the way I wanted it to be, but that’s the way it happened, so I have nothing to regret.” Johan Quezada told me, barely a week before he became the first of what I hope will be many 2020 players to re-debut this year. “My daughter was born and I made my debut. Even in a bad year, I want to say that I still found a lot of good in it.”

To completely put the 2020 season behind us, or just to shrink it to nothing more than The Mickey Mouse Title The Dodgers Won and the year Salvador Perez stopped grounding into double plays, is both tempting and an obvious mistake. It was shorter, it was quieter, and it was much weirder, but every pitch and every name on the field during that haunted semi-season goes into the record books all the same. Every game involved big-league players playing big-league baseball, even if the other stuff that generally marks big-league baseball as such was absent.

Before saying goodbye and getting ready for that night’s game, Elliot Soto thought back to his day bouncing around the Oakland Coliseum stands back in 2020. “Spending a few innings as the only person watching Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani play baseball was a good time,” he said. “All things considered.”