As the parent of an 18-month-old, I’ve been reading a lot lately. That is, if your definition of reading includes thumbing through sheets of increasingly careworn and spittle-soaked cardboard, reciting the 30 or 40 words that compose each tale from memory, and pausing innumerable times to acknowledge any shape that may evoke the holiest of trinities: ball, bug, star.

At first—when I had a mere 10 months of experience in this arena—I believed that reading to my child would be straightforward, if a little repetitive. I thought boredom would be the biggest obstacle. Little did I realize I would be jeopardizing my own sanity, because the more time you spend with these texts, the more you feel drawn into their deep wells of chaos. They may help my kid gently drift off, but the confounding logic I encounter in these books keeps me up at night. Let me initiate you into some of the mysteries that have come to plague me.

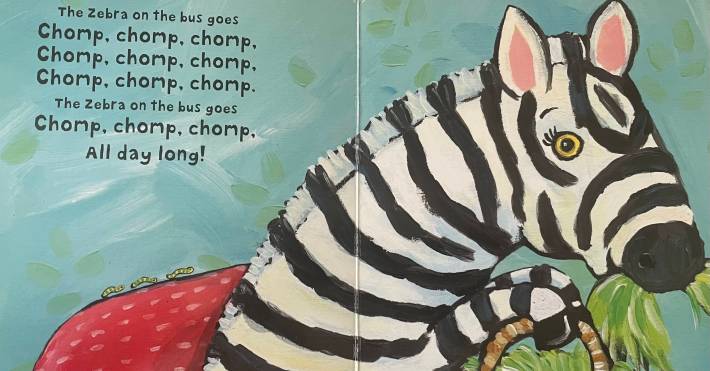

The Wheels on the Bus, written and illustrated by Jane Cabrera

Before I had a kid, I questioned the need for the abundance of Wheels on the Bus variations. Now I understand that there is no upper limit to the ideal amount of things that could happen in threes on buses. All day long, all through the town—a la Speed, it doesn’t matter what we’re doing as long as the bus keeps going. In Cabrera’s iteration, many animals do many things on a bus winding its way through the jungle. But these three caterpillars show up several times, yet throughout the book they remain completely unacknowledged. (Lest you think this is because the word “caterpillars” presents a problem syllabically, let me assure you that Cabrera could not give less of a shit about that. She’s more than willing to force you to flail through “the bush babies on the bus go snore snore snore.”) I’m always tempted to ad lib “the caterpillars on the bus go scoot scoot scoot,” but something holds me back. Perhaps the premise is that the caterpillars must be ignored so that the zebra can shine. Perhaps the caterpillars are an Easter egg, and the love of the few who discover them will make up for the indifference of the wide world. Perhaps the caterpillars represent the pauses between the notes, the little silences without which there would be no song. We may never know.

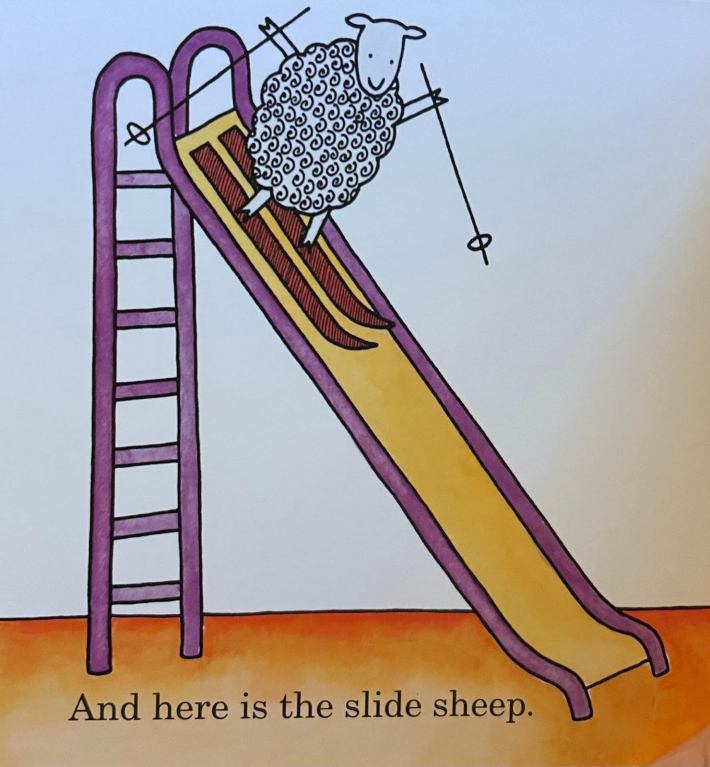

Where Is the Green Sheep? by Mem Fox, illustrated by Judy Horacek

Red sheep, blue sheep, bath sheep, bed sheep—sure, sure. I’m willing to suspend one layer of disbelief per sheep, at least in the opening pages. But the slide sheep doesn’t belong. You’re telling me this ovine climbed a ladder while carrying skis and poles and put them on while balancing at the top of the slide? Or what? What is the alternative? I can see how things progress from here. The future is clear, unambiguous, inevitable. The past, however, is utterly opaque.

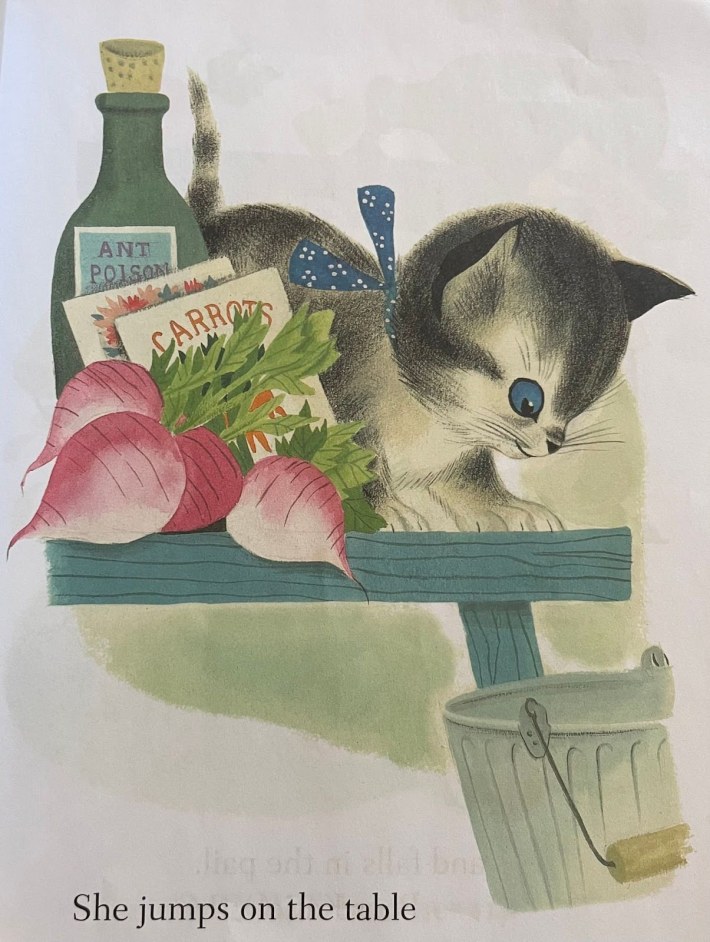

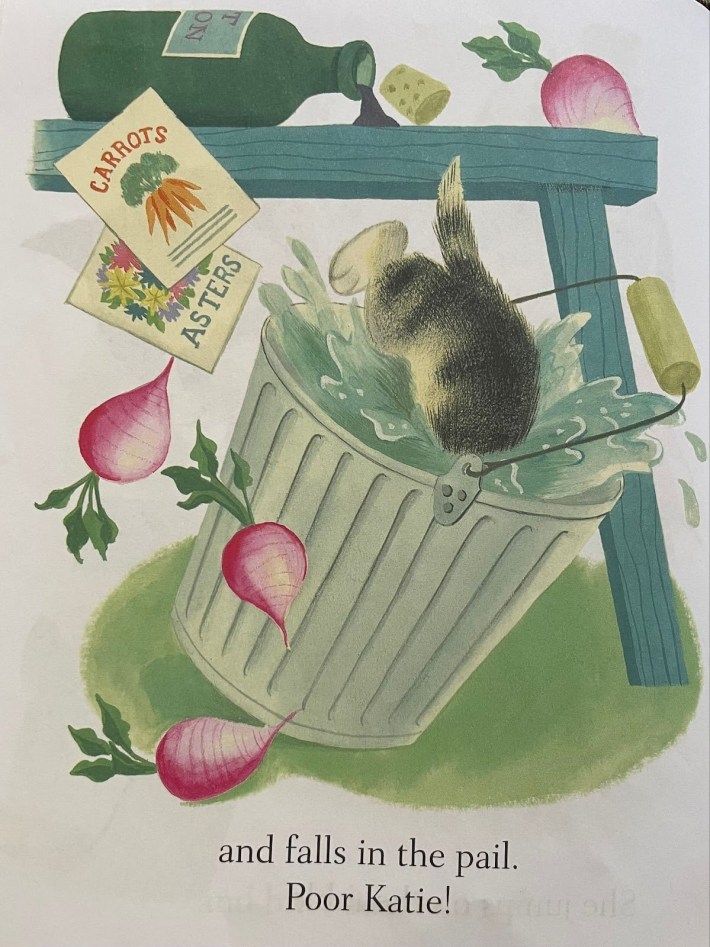

Katie the Kitten by Kathryn Jackson, illustrated by Martin Provensen and Alice Provensen

The bottle of poison seems like an ominous Easter egg to plant in the tale of one kitten’s mishaps. Then again, there’s no sugarcoating in Katie the Kitten. A few pages before this incident with the bottle of poison, Katie climbs an old apple tree in hopes of murdering three baby birds. The thing that gets me about the poison is that it’s like Chekhov’s gun. The dark promise is fulfilled: the poison spills. Sure, in a way this is like every other mess Katie has left in the wake of her rampage. But this is a book meant—one presumes—for parents to read to their tiny children, parents who have spent their days triaging messes left in the wake of their progeny’s rampage. This bottle of poison asks: Are you forgetting something important? Perhaps even deadly? Which is, of course, the scariest of all questions to plant in the sleep-deprived mind of the adult who is just trying to make it through the bedtime routine.

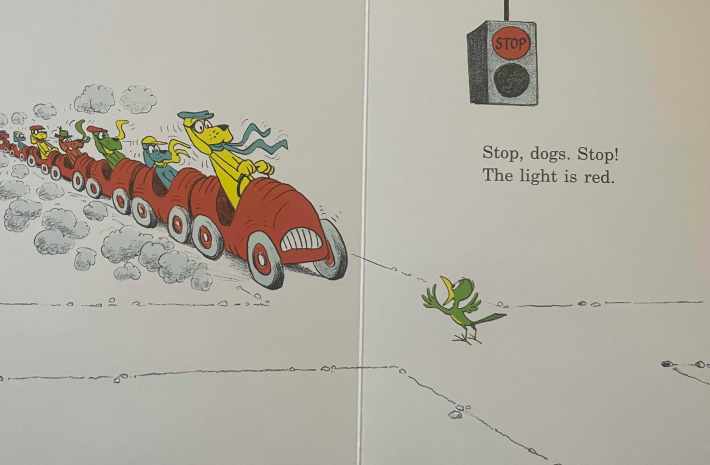

Go, Dog. Go!, written and illustrated by P.D. Eastman

On first glance, this bird is a run-of-the-mill busybody. Admittedly, I have not read the unabridged version of Go, Dog. Go! for several decades, so perhaps the board book omits crucial character development for green bird. And perhaps there’s a kind of justice in the bird telling the dogs how to go, considering that later a bunch of dogs are going to throw a rager in the bird’s tree. But why is the bird crossing the street by foot? Why has the bird stopped in the exact center of the intersection? Is the bird the narrator of the entire book, popping down from on high just to illustrate how all these dogs are puppets in the face of avian omnipotence?

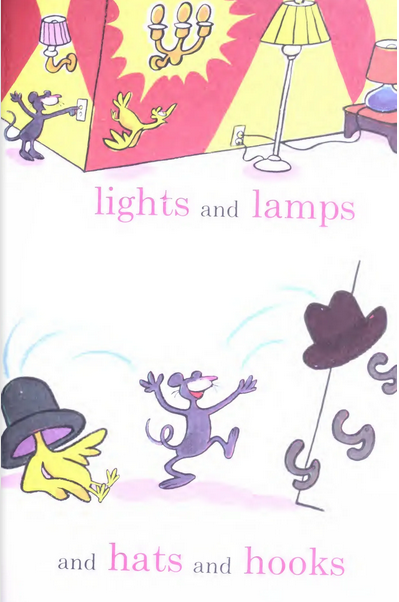

In a People House by Dr. Seuss as Theo LeSieg, illustrated by Roy McKié

The floorplans presented in kids’ books often have a pleasingly prismatic quality, like House of Leaves but wholesome. Interior windows, impossible walls, cottage hallways spanning hundreds of feet. It’s like the world reflects the experience of a dizzy, hangry toddler careening through timespace in search of a rule to break. But there’s something about the crimson faux-shadows and the mouse-height hooks that troubles the brain beyond the capability of your average funhouse mirror. Stare long enough at this page, and you will come to feel as though babyproofing is futile. A home’s capacity for mischief and hazard extends inward infinitely, fractal-blooming from every object into every moment.

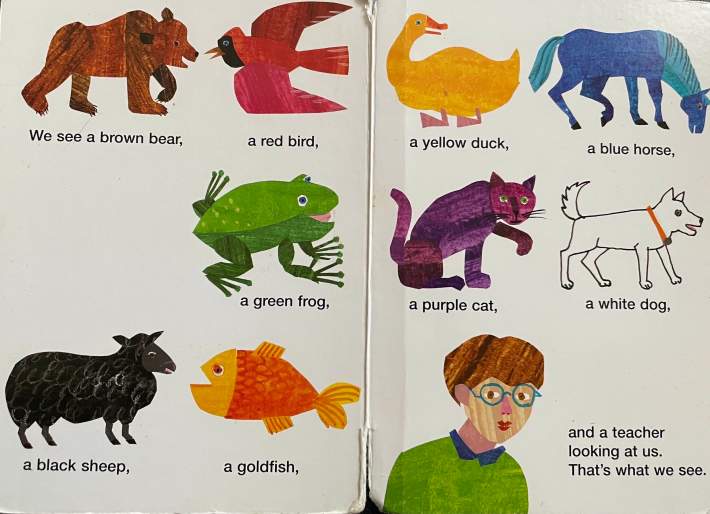

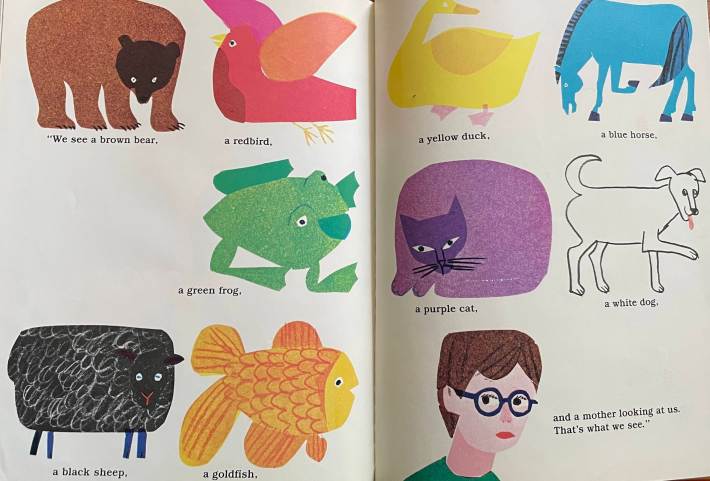

Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin Jr., illustrated by Eric Carle

We’ve acquired several versions of this book over the last year-and-change, as one does. My kid eats all that repetition up: “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see? I see a red bird looking at me. Red Bird, Red Bird, what do you see? I see a yellow duck looking at me.” But the more times I’m confronted by this recap at the end, the more I struggle with the fact that most of these animals are not looking left at the animal who first names them, nor are they all looking right at the animals they see in turn, nor are they looking outward toward the viewer (which would probably have been the safest choice, if no one could figure out how to apply the 180-degree rule to this scenario). We can all agree that this is a book about looking and seeing, right? We’d have no vehicle to get from the brown bear to the children without the hot potato of the gaze. Either all these illustrations are meant to evoke the Mona Lisa effect, or more than half of this book is made of lies. In modern editions, we can trust the brown bear, the black sheep, maybe the goldfish, the teacher, and the children. Since it would have been easy enough—even back in the day—to construct the book with illustrations in pairs so that the brown bear and red bird face one another, and to flip the images as necessary as the narrative goes on, I’m forced to conclude the point of this book is to teach toddlers to question everything. I have one question for you, Bill Martin Jr.: Why?

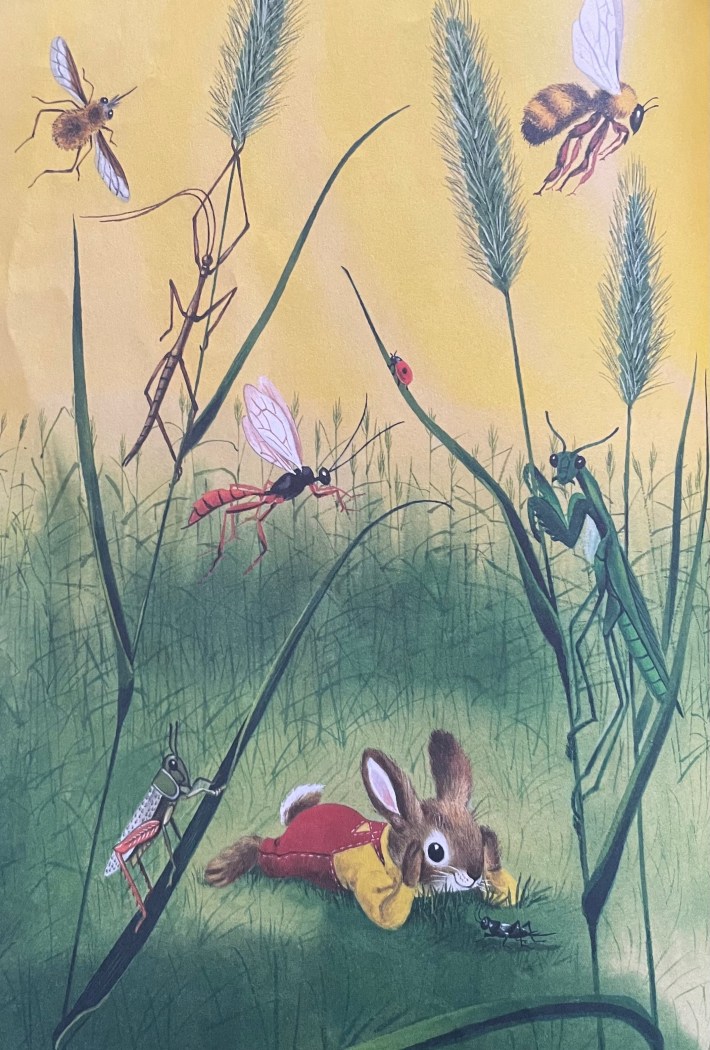

I Am a Bunny, written by Ole Risom, illustrated by Richard Scarry

How big is Nicholas the bunny? Exactly as big as circumstances demand in order to optimize his cuteness. The shapeshifting is mild, sure, but it’s inarguable, and Nicholas’s savvy understanding of how to charm us is creepy in exactly the same way influencers who actually get you to follow are creepy. Nicholas is meant to make you smile. He shelters from the rain under toadstools and puts on tiny mittens when it snows. He could be sweetness incarnate, he could be a metaphor for childlike wonder, he could be the spirit of the seasons, he could be the pleasure we take in dollhouse furniture made animate, he could be the embodied vibe of a ladybug, but I’m telling you: This li'l guy is not a bunny.