The Phillies have some weird-ass hitters that love the extremes. Even the good ones could be described this way. Trea Turner had a terribly slow start that he has now thoroughly bounced back from; he has a 3.7 fWAR as the end of the season approaches, despite the fact that over the course of his 100-or-so pre-ovation games, he'd racked up a mere .657 OPS. Bryce Harper, who is coming off elbow surgery, got his power back around August. He hit 10 home runs in the month, tripling his total for the year.

And then, of course, there's Kyle Schwarber, who I don't really like to talk about, but who needs to be mentioned in any story in which the words "weird" and "hitting" appear in the same sentence. Schwarber has 44 home runs—this is very good, enough for a share of third in all of MLB, and as many as Shohei Ohtani (may he heal rapidly). But Schwarber also has 0.4 rWAR and 1.3 fWAR on the year, which means that advanced stats grade him as around replacement level, even with those 44 home runs, because he is such an impossibly poor defender. Not great! Then again, Schwarber has an impressive 120 wRC+, which basically means that he's 20 percent better than league average at hitting the baseball. That is not weird; that is good. But how Schwarber gets there is very weird. He bats lead-off. He has a .197 batting average. He's second in the league in walks. He leads the league in strikeouts. He has a .345 on-base percentage. He is unfathomable. He is Kyle Schwarber.

This sort of thing is not unprecedented, to be fair, albeit usually in smaller doses. Schwarber's pulling off a jacked-up version of Yasmani Grandal's 2021 season. These are two three-true-outcomes kings doing what they do, except Schwarber is throwing in worse positional adjustment thanks to being a left-fielder, and also Grandal managed to pull his batting average up to .240 by the end of the season. Schwarber looks to be maintaining his season-long pace through the remaining games on the schedule. There's literally no one doing it like Kyle Schwarber right now. If you think about it that way, we are all blessed to witness it.

I was reminded of all of this during an August series that the Phillies played against the Giants, a series that was most notable for the fact that both the second and third games involved come-from-behind moments for the Phillies against Giants stopper Camilo Doval, who finished with a 2.60 ERA going into the second game. In that fateful game, Doval threw two balls to Schwarber before deciding to intentionally walk him, only for Trea Turner—our other Phillies main character—to walk off the Giants with a hard-hit single. In the third game, it was Bryce Harper who hit the solo home run against Doval in the ninth inning, dragging his ERA up to 3.09. It had a similar effect—the Phillies tied the game and went to extras. There is no need to go into what happened after that.

All of this—and some moments in Philadelphia's recent series against the Braves—made me wonder why the Phillies can rack up runs against good pitchers like Camilo Doval, but struggled against the plethora of interchangeable middle relievers that Gabe Kapler threw at them seemingly at random, discarding one for another as soon as they hit the three-batter minimum. (Gabe Kapler is a freak, and he does not care for the allotted room in your scorebook for pitchers in the game.) Maybe if the Phillies could score some runs against those pitchers, Kapler would stop making so many decisions every game, and so I wouldn't have to deal with watching 10 Giants pitchers over the course of one nine-inning game. I am very nearly off topic here but my question was: have the Phillies ever considered doing that, rather than saving all their efforts for Camilo Doval and his 2.60 ERA?

Those Giants middle relievers, including the Tyler-Taylor "Weird Delivery" Rogers twins, were not schlubs, to be clear. Many were, in fact, also sub-3.00 ERA pitchers at the time. Such "facts" did not deter me then, and will not deter me here. I had confirmation bias on my side, and I was going to do some statistics to prove that I was actually right, and that the Phillies struggled against random relievers with mediocre-to-bad ERAs and hit well against competent ones.

The issue with setting out on a brave statistics expedition is that 1) sometimes you are wrong and 2) worse, sometimes you wind up with something uninteresting. Common sense dictates that teams or players that hit well against good pitchers will also hit well against bad pitchers; this will, on balance, be true even of weirder hitters like those on the Phillies, although they might look weirder in getting there. And confirming that wouldn't really be interesting because it wouldn't really tell you much that isn't already known, although it might give you the information you need when arguing against feral Phillies fans who've gotten it into their brain that the team hits better against good relievers than against bad ones. Even if you didn't confirm the expected outcome, it could be mostly chalked up to variance. Players aren't changing their approaches based on the ERA of their opponents. In this case, they are just going up there to hit in the weird ways that they do.

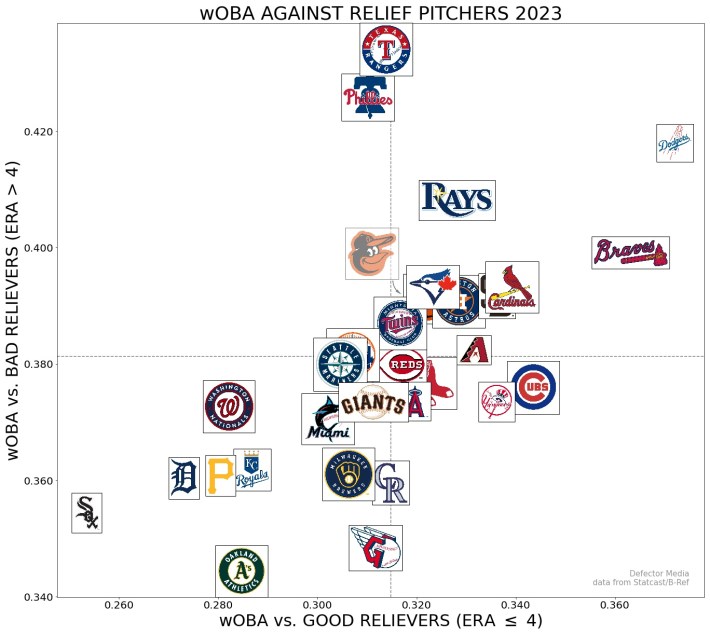

Anyway, because I'm a paragon of bravery and also because I dedicated hours of my life to this project, you still get to the see the results. I set a minimum innings requirement for the relief pitchers at 20, mostly because the "good reliever" vs. "terrible reliever" binary is based largely on vibes and reputation, and a pitcher with a spotless ERA and one inning pitched doesn't fall into either category. I defined a "good reliever" as a pitcher with an ERA of 4.00 or under at the current point of the season, and a "terrible reliever" as a pitcher with over a 4.00 ERA. I did this because it adheres to the binary that I have constructed in my brain, which is inherently retrospective; it is, obviously, not especially scientific.

And then it was just a matter of grouping by team and calculating the wOBA (our chosen catch-all metric of offensive production) of each team in each situation. Which gets you a plot that looks like this:

While most of the teams fall in line about how you would expect, with the best hitting teams doing better than average against all relievers and bottom-hitting teams doing worse, the Phillies do stand out a little bit. It just happens to be in the, uh, exact opposite way that I'd thought.

The Phillies, like the Texas Rangers, perform around league average against good relievers, but perform notably better than league average against bad ones. If you look at their wOBA+ against bad pitchers, which in this case just means the Phillies' wOBA divided by the league average wOBA against bad pitchers and converted into a percentage, it sits at 111. That's about 11 percent better than league average.

Team wOBA/wOBA+ Against Bad Pitchers (ERA < 4)

1. Texas Rangers – 0.434 / 113

2. Philadelphia Phillies – 0.426 / 111

3. Los Angeles Dodgers – 0.418 / 109

4. Toronto Blue Jays – 0.408 / 107

5. Atlanta Braves – 0.399 / 104

Even if I was wrong, that's still something! All of that effort didn't exactly go to waste, which is the sort of statement that seems less convincing when you type it out like this, but which I think is true. I disproved my previous misconception, and I generated a nice little graph, and it has the Dodgers at the top right corner and the A's and Sox in the bottom left, as God intended. I like to think that it was Kyle Schwarber who taught me to have this adaptive capacity for reflection upon my own statistical output. Thank you Kyle Schwarber.