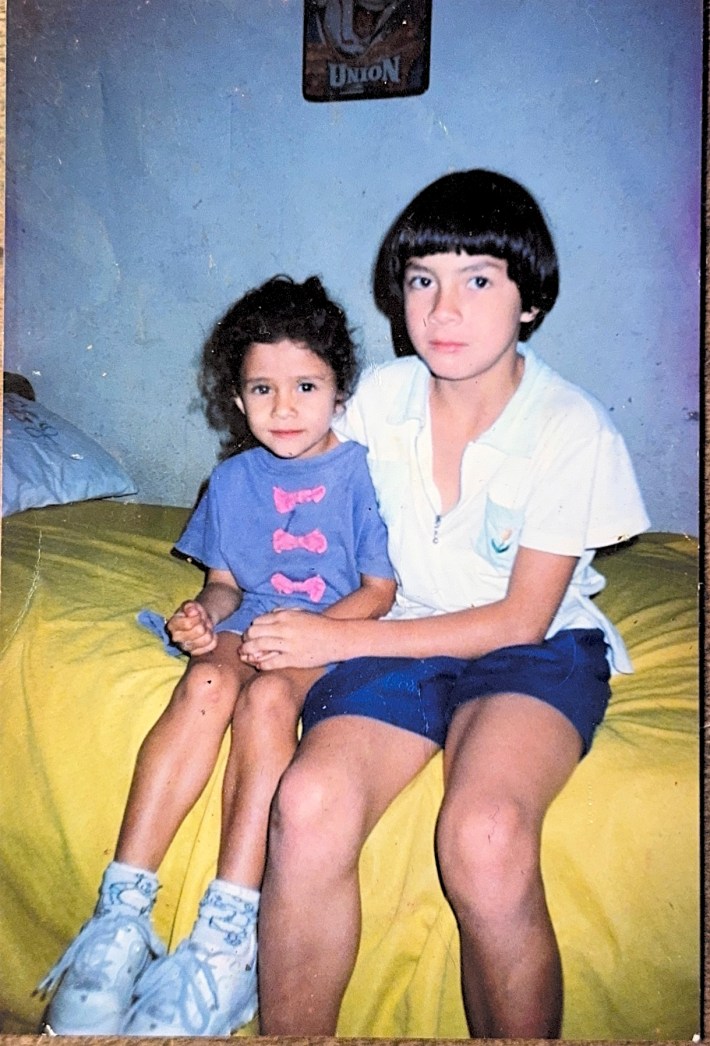

Laura Mata López was born and raised in a low-income community in San José, Costa Rica. Some of her earliest memories were of the impact poverty and a lack of support for mental health had on her neighbors. Mata López's mother and grandmother had migrated to Costa Rica from Colombia during the Colombian civil war, severing them from their roots and family. For a period of time, Mata López's family was undocumented in Costa Rica, although their route to citizenship there was fairly easy. "Even then, I always had this identity of being a migrant and being an other," Mata López said.

When Mata López was 12 years old, she immigrated to New York City, where her mother cleaned houses. When she started school, Mata López became selectively mute, a condition she could not name at the time. She was overcome with a knot in her throat when her mom dropped her off at school, only regaining the ability to speak when she returned home and spoke with her family in Spanish.

Mata López eventually excelled in school, and she applied to college with the intention of becoming a nurse. There, Mata López specialized as a psychiatric nurse and served marginalized communities, many of whom had never seen a mental health provider before, and some of whom were undocumented.

Mata López started her doctoral research at Johns Hopkins University, where she began a complex, community-based study on suicide risk among Latina immigrants. Her work has been federally funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Institutes of Health, which awarded Mata López a competitive Diversity F31 grant, which supports PhD students from underrepresented backgrounds in science. On April 29, Mata López learned the Trump administration terminated her grant, along with all other Diversity F31s.

This experience has been logistically, financially, and existentially destabilizing for Mata López, and has made her doubt if her work is possible in the current academic system and climate. "Trust is not easily rebuilt when harm is done," she said. "I'm not talking about just the communities that we're serving, but I'm also talking about the scientists whose data was ethnic and disability status data and gender identity data is now being used to terminate our grants." I spoke with Mata López about her undocumented collaborators, the structural basis of suicide among Latina women, and the lives she hopes to save.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you become interested in working in healthcare?

I don't really see myself ever not being a nurse, now that I look back, but it was sort of accidental. My first semester [at Boston College] I really struggled. ... I was 18. I had been in the U.S. for barely six years. Two of those years totally mute, and I was expected to just be a traditional college student. I wasn't doing well in my classes. I was really struggling. There was a dean at the time, ... Catherine Read. ... She had an open-door policy, and I would go to her, and I would cry and cry, and I would say, "Please, let me out of this program. Please, let me drop out." I did that for ... maybe a few weeks before she was like, I have this leadership program. It's for students that are like you, who ... don't really have much where they come from.

Through that program, I got paired up with another white woman. Her name is Judith Shindul-Rothschild, also retired now, but she was a psychiatric nurse practitioner. ... I remember saying, "What is that?" She explained the role to me, and ... it literally clicked in my head. That's what I want to do.

I felt it in my heart that if I did my PhD at the time, that I would just replicate the research that my mentors were doing in white people. It wasn't even a possibility in my mind. So I made the hard choice ... and said, I have to go and practice clinically. My masters had been funded through ... Nurse Corps Scholarship Program. It's part of the nurse loan repayment. They pay for your master's, and you go and you serve in an underserved community. By this point, I was a street nurse.

I think I tried to block my experience as a migrant, because there was this sense of, I don't want it to shape my path more than it already has. And then I end up in this job, and the first HIV diagnosis that I had to give ... he was an undocumented Latino. ...That diagnosis that I had to give, that patient, that changed me. I was becoming a nurse practitioner, and my role was changing. I was going to be prescribing, giving treatments. And it dawned on me ... that is not a clinical choice in this country. It's fully guided by what is accessible to them based on their insurance access.

I went on Google and said, where in the United States can undocumented people have the best chance of receiving care? The number one answer was California. ... I worked in a little federally qualified health center in Northern California, in a county that experiences a lot of geographic disparities, predominantly undocumented Latinos, a very high proportion of undocumented Latinos. I arrived in 2017, and just the year before, the community hospital had closed.

In federally qualified health centers, you have to give patients questionnaires. ... You have to give everybody the PHQ-9, [and] the last question is about suicide. ... There was either this hyper-reactivity of, they said yes on the question, you need to go to the hospital. The patient would immediately say, "Wait, why? I can't. I have an entire shift. I can't not go to work." OK, now we have to call the police and get you there to an ambulance. .... Sometimes they wouldn't even read the PHQ-9, or they would read it and they would just let the patient out the door. They would place a referral to us in mental health, which could take us six weeks to get to. There was a point when we had 130 referrals.

There was this reality that I will never get through these 130 referrals. We'll never get to them. And some patients literally might die or might get lost in the system in the midst of it, because the processes we have are not efficient in being able to provide them the care that they need. What I really, truly couldn't sit with was the fact that we were actively re-traumatizing the community in the process of getting them help.

I became a specialist in developing suicide risk prevention risk assessment protocols. ... essentially, in layman's terms, identifying patients who were at risk of suicide. Not just identifying but being able to respond and shifting the .... response to be a humanizing experience. That's all that it was. To really be centered on, this is somebody whom we may not ever be able to touch again. How do we get them to come back? That's how we prevent suicide.

Pretty quickly, within a year, it changed. There was nurse-led suicide risk assessment and nurse-led prevention protocols and response protocols. They just became a mechanism of triaging systems. ... [Latina immigrant mothers] were my highest-risk patients when it came to suicide. I couldn't sleep at night, sometimes.

In the middle of COVID, we had a patient who called the clinic in our front desk. I was working from home. ... On this day, I will never forget, the patient just called and said "My boss raped me and I want to kill myself." And went silent, but stayed on the phone, and I got the call maybe five minutes into this from my manager: "We can't get her to talk." I said, keep her on the phone. I'll be right there in 10 minutes." I drove faster than I've ever driven. But because of the trainings we provided, this exact thing that had to happen, happened. That staff member kept that woman on the phone line, which was part of our protocol that we had developed.Your only job—you don't have to do anything—your job is to be there for that moment. Listen to her. Don't hang up the phone. Flag your manager. Immediately get help. They will call help. Keep that person on the phone. Everything went the way that it had to go. And I got to the clinic, and I got her on the phone, and she became my patient.

I've never published this. We've never published it because in federally qualified health centers, in these under-resourced settings, you have so much science that's happening on the day-to-day. But it's being driven by real need.

It does sound like you were practicing a lot of the things that you're now investigating without necessarily being an academic.

It became about going back to school and turning it into a question.

Suicide is more complex than we're talking about. It's gendered, and it's highly contextualized. And it truly is a consequence, based on my experience—and this is what I'm trying to quantify—it's a consequence of institutional and historical oppression. That's how it manifests itself. And so my research has become a process of identifying that.

What steps had you taken in your doctoral research up to the point when you learned about the termination?

One of the hardest parts about this program has been sticking through this path and in being stubborn and collecting my own data. But I feel so strongly about it, because there's just no data like this in our community. And to me, there is very little value in analyzing existing data that just wasn't answering the questions that I was asking. So my proposal is a community-engaged study, and I'll talk a little bit about what that means. I use mixed methods. So that means I combine different types of methodologies to be able to give us a more comprehensive understanding. What is suicide survivorship among Latina immigrants? What is this phenomenon? How is it experienced? And how is it experienced in the context of gender? And the second part is a quantitative arm, which involves being able to examine and identify risk and protective factors that are culturally specific to Latina immigrants.

When I was applying for this F31 grant, I was really discouraged in the PhD program. In fact, I was back in that freshman year of college where I was ready to drop out. I had signed my little form and everything because I had lost my advisor last summer, and she was the only Latina doing this work [and] she left the university. It felt like, "How can I do this?" ... For the first time, I could have had a mentor that looked like me, right? To me, that was important at that time. It felt like the end of the world.

I got this little pilot grant for $2,000. For about a year, I got to envision this group of five women, most of whom are undocumented, who have their own experiences of suicide survivorship. They've co-led this work with me since the very beginning. I remember when I was selecting them, I created a profile for all of them with all these methods that we utilize to do this. But I really was just thinking [about] the patients I've lost that I haven't been able to get to in time.

The community health workers in our clinic—all Latina immigrants themselves, half of them are undocumented too—we need them too. Because when we were at our clinic, our community health workers, without them, I wouldn't have been able to do my job. So I needed them too, because we needed them to really embed ourselves in this work. To be able to do it right, and to be able to get these women to tell their stories in a way that was meaningful. ... We meet monthly, we co-design all the aspects of this work

[This] little $2,000 pilot grant before my NIH [proposal] definitely made my NIH proposal a look a lot better at the time. I got funded on my first attempt.

Can you share your experience of learning about your grant becoming terminated?

Because this is a really complex study, I had finished collecting the first arm of my study, which was my qualitative arm, I actually had about half of my data. ... It's a combination of interviews and focus groups, and there were two arms embedded within that arm. It was 20 Latina immigrant women from the Baltimore metropolitan area with lived experiences of suicide, survivorship and migration-related trauma. And then it was also 20 community leaders, providers, religious leaders, promotoras, nurses, doctors, stakeholders who are already playing an active role in suicide prevention efforts in the community.

Research doesn't happen overnight ... especially not when you're doing it in a community setting, with an engaged approach. It takes time, and there's also steps. I was in the step of trying to analyze this data, building my survey, and then my fellowship got terminated. But I already knew it was going to be terminated months prior, and so it really became, about organizing within the university with our union to help us put pressure on the university to make this research [still] possible when it got terminated.

I am the only nurse leading this work in the School of Nursing with this community in this context, and I have always said that with pride. I come to the community and I say, we're doing this research as a part of Hopkins, one of the best institutions in the world, funded by the federal government. ... And it means a lot to the community, especially when you have somebody from the community who's serving as a bridge between those two, when there's some link. But then I found myself in a boat abandoned by my own institution.

I found out about my grant being terminated on the morning of April 29. I got a letter, and it got terminated because my research was categorized as being DEI, solely because I was part of the F31 diversity program. The only thing that makes it different from the non–diversity programs is that we could self-identify to the NIH as [being from] minoritized backgrounds.

The NIH harbored our identity data. It didn't benefit us in any way. In fact, after that, our applications went into the same pool as all the incredible, regular, white F31 non-disabled, non-queer, cis, non-migrant [applications], and we all compete for the same funds. So the only thing that made this mechanism different was that we could talk about the pride that we felt. I literally wrote this: Not anybody can do this research. Not anybody should. But if there's anybody that can, it's me. And they needed to know that I'm a Latina immigrant. That I speak Spanish as my first language. That I've taken care of this community. They needed to know because that's what makes this research possible.

It's very hard to come back from that and to stay in a system that has targeted you and your work in that way.

Could you talk about what the next steps look like for you and your research?

To me, Hopkins, and every academic institution, has a responsibility, to ensure that the funding that is being cut from trainees, especially [researchers in early career stages], can finish without disruption. Because in 100 years, we will have to talk about this. We will have to dissect why this happened, and the research that was lost and the lives that this cost. Institutions will have to defend the actions that they took.

When I framed it like that to our institution, we weren't getting the adequate answer. So I did the best thing that I know to do, which is to organize through our union. We put pressure on the university for three months until they announced a mechanism of "bridge funding" that will be one year long. It will be enough for me, but it will not be enough for all.

To these institutions, the humanity that is behind these cuts is not just being lost, but it's literally being seen or categorized as less important. The risk of fighting for this small group of scientists who are being targeted for their ethnic identity is just too high in the context of what can come for us, without realizing that what is happening is that allowing this to happen will mean that no minoritized person, no person with a disability, no military veteran, no person who comes from a non-traditional background will ever be able to compete at the very same level. ... You can be just as qualified, and it will never be enough. ... To me, that's not real equity. It's not real change. It's not real science.

My best science happens when I'm in my community, talking my ideas with some of these women [who may not have] a high school degree. ... And I finally see so clearly that it doesn't matter how much you push yourself into a system, how much you bring in your community, they will other us. They will collect our data. They'll pull it all out from under us. They don't care that our community is dying by suicide. They don't care that [the preliminary findings of my qualitative] research [show] that the biggest driver for that among [Latina immigrant] women in our community is that they're being separated from their children. That this is preventable [and] that our own policies are causing it.

There's a lot of conversation around "What do we do? How do we change the language in our grants?" ... No. Doing all of that would make those five women that have become my mentors, my co-PIs, feel less than. God, never. I'd rather be unfunded for the rest of my life than change my science as a consequence of this.

I wanted to ask if there was anything else that we haven't had a chance to talk about.

What led us all here is that we have stopped humanizing science. Our communities and people and Americans don't even get to read our science. We're thinking about how we abstract categories and rewrite grants, and all I see is people in the shadows, more and more. I keep saying this again, but if that's science, then I don't want it. Then I don't believe in the scientific infrastructure that exists. I don't want it, and I don't think I'm alone.

I realize that my approach is a risk. But I don't think of risk. I think of justice. I think of the women in my community who are dying, on how to help them. And changing the language in my grants and excluding them? ... That's harm, and I don't want it. So we leave and we come back and we hope for justice and revolution and rebuilding. I don't know if I'll be a part of it, but I hope it for whoever stays.