I recently stayed at a blandly business-oriented hotel in San Jose in order to celebrate my birthday, drink a tall boy, and watch the Sharks lose. You know this type of hotel. There were white duvet covers, white sheets, beige walls, dark wood for the closet and bathroom doors. There was a nice light under a wall bench to help you find your way to the bathroom in the middle of the night. The soundproofing was good.

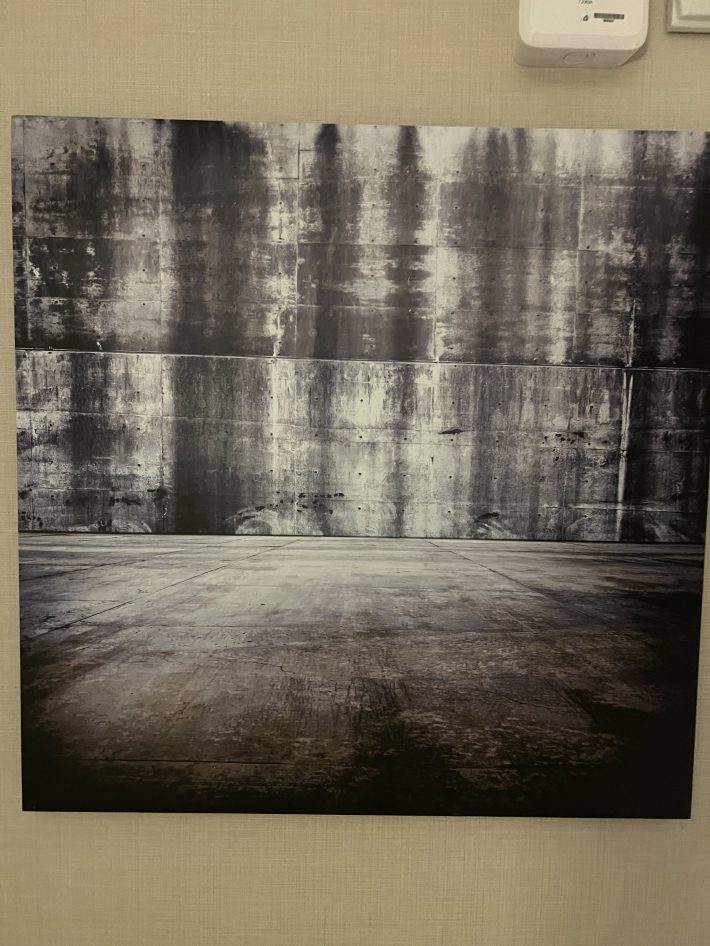

There was also, of course, a picture on the wall. There is always a picture on the wall in hotel rooms. It was a photograph, and it showed a cement wall and floor belonging to what seemed to be a warehouse building.

If you have never thought for even one second about hotel art, let Hotels.com tell you that once upon a time hotel art had a reputation for "faded reproductions, generic photography, and soulless sculpture." Fifteen years ago I would have told you that hotel art was mostly large, semi-abstract red flowers, and six months ago I would have told you that hotel art was mostly black-and-white photographs of local landmarks, often a single detail in extreme close-up. The content of the image in my San Jose room may have been different than other hotel art I have seen, but my brain felt a pleasurable little thrill at dumping it into the generic artsy photography basket.

If the function of the art on the wall of a private home is the expression of the resident's personal taste, the art on the wall of the average hotel is there to reassure you about the refreshing lack of personal taste that you can only get from a corporate chain. The art, be it sailboats or pastels, says that while some effort has gone into this room, nothing weird is happening here. The perfect hotel art is the art that you don't notice at all.

The idea of "real art" is a fucked-up one, but that doesn't mean it doesn't convey meaning. Cultural norms helpfully tell us where to find the bathroom in a restaurant, and they also tell us—through childhood field trips, through movies, through television shows—that the place we go to engage seriously with art is a museum, and that we go to museums to pay a kind of considered attention to art that we expect to be repaid, maybe in an expanded or intensified relationship with the world, maybe merely in retaining the capacity to pay a certain kind of attention. The book version of Ways of Seeing cites a table showing that more than anything else, a museum reminds people of a church, and proposes that a lot of people believe that "museums are full of holy relics which refer to a mystery which excludes them." I love that book, and it is a lot smarter than I am, and furthermore I am not a churchgoer. Still, I have always imagined that most people go to church in order to access a mystery specifically intended to include them.

I don't think anybody reading this needs me to tell them that cultural authorities have over the years made bad and wrong decisions about what should hang in museums, sometimes for predictable reasons of racism or sexism, sometimes for more idiosyncratic reasons of bad taste. The very idea of a piece of art as something that needs to be struggled with and learned from can distort the relationship between a viewer and the piece in front of them. An embarrassing childhood memory: I asked a relative which of a series of paintings we were looking at was worth the most money. My relative, apparently a fan of the Socratic method, asked me to guess. I picked the painting that I thought was the ugliest, having somehow acquired the belief that surface beauty was a demerit when it came to taking art seriously. I was wrong, it turned out; I had allowed the idea of difficulty to plant itself squarely between me and the art in front of me.

In some ways, the hotel stands on the opposite pole from the museum. Not because the hotel business is unconcerned with aesthetics. The hotel business is obsessed with aesthetics. Every day scholars of the hospitality industry churn out studies on what putting something into a handwritten font does to guest messaging. The chapter in The Cornell School of Hotel Administration on Hospitality: Cutting Edge Thinking and Practice on Guiding the Guest Experience (Chapter 8, not to be confused with Chapter 30, on employment law and titled "You Can't Move All Your Hotels to Mexico") identifies the Sources of Pleasure. You may not have known this, but there are three Sources of Pleasure: sensory pleasure, aesthetic pleasure, and, finally, achievement pleasure. Some concrete suggestions to implement these pleasures: "Display dessert samples in an attractive display that will both heighten anticipation and somewhat decrease the boredom of waiting." "For instance, if your customers are in day five of a six-day trip, you may frame the remaining time as 'two days left' rather than 'Day 5.' This frame makes the remaining time seem more precious. Focused on the transience of their vacation, guests would become more aware of their pleasure and enjoyment." Great ideas. Also they suggest lobster tanks.

If these suggestions seem a little underwhelming, pleasure-wise, there is what is called in the industry the design hotel. The design hotel is maybe too easy to make fun of from the opposite direction. A 2012 paper for the Annals of Tourism Research, by Lars Strannegård and Dr. Maria Strannegård, describes a hotel where "[t]he toilet paper is wrapped in black silk paper, and the grey shade of the towel is said to be unique for the hotel." The language used around these properties is even easier to make fun of. In the words of Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, "a common theme emerging from the coolness literature is that cool things tend to be different from the rest of the pack." This feels irrefutable. But the art at design hotels, apparently, is actually pretty good. It’s produced by artists whose names are attached to it, and often rented or borrowed from a local art bank. And just like any innovation begets sad imitations, it seems likely that the surface appearance of this art, if not the quality, is trickling its way down, leading to art-coded images like the one hanging on the wall of my hotel room.

Nevertheless, as the two Strannegårds point out, the art of any hotel lies not in the particular image hanging on the wall, but in the experience. And that experience is decidedly not one of opening oneself to somebody else's vision. It is about being the paying customer around whom a whole little world revolves. Sometimes that world includes free waffles that you make yourself in a rotating waffle maker, and sometimes it includes high-end art, but always always always it includes the ability to complain when things aren't the way you want them to be.

Which is maybe in fact closer to what it meant to be a patron of Bronzino than going to a museum and looking at a painting that somebody else has decided is good. The fact that these hotels are profit-making endeavors with the profit-making obsession of pleasing the customer doesn't, in itself, bar them from being art—we mostly all agree that movies are art. The insane brand standards could, from a certain angle, be seen as the formal constraints that so many great art forms impose upon themselves, like haiku.

A recent New Yorker issue has a great profile of a chef who says, "People talk about chefs being artists, but it's always within this box of 'pleasure' and 'you need to be nice' … there also needs to be a part of disgust in art, and something that challenges you." I don't know that I agree with this; I think there's plenty of art that operates precisely by drenching you in beauty, that achieves aesthetic shock by erasing the disgust and challenges that we slog through every day. I'm not sure my cement wall photograph did quite that much, but in San Jose I was certainly in no mood to be challenged.

The act of staying in a hotel is extremely weird. I often find myself thinking of this Drew Magary piece. I am not rich enough to be a boring asshole, but under the right circumstances staying at a hotel can make me feel like one, like all the gravity and friction of my life has been removed and replaced with beige. If we are going to start thinking of hotel stays as art, I am going to be an extremely staunch hotel academician and take the position that the highest and best version of the hotel is the one that most replicates being in a sensory deprivation tank.

In this hushed atmosphere, even the tiniest disruption achieves a huge importance, and the oddity of the subject matter of the picture on my wall was a momentary reminder of the unseen corporate behemoth doling out my Sources of Pleasure. I asked the front-desk person if she knew who made the picture on the wall of my room, which was a question that seemed reasonable in my head and then ridiculous as soon as it was coming out of my mouth. She said she didn’t know, that she was sorry. I imagine there are several studies in Cornell Hospitality Quarterly that have determined the optimized way to negatively answer questions like mine.

So I took a picture of the picture with my phone and ran it through a reverse image search. I got thousands of similar images, and a whole list of results of "Huge Grungy Concrete Room stock image." And then, there it was. It turned out I could buy the image, royalty-free, off the stock image site Dreamstime.com, for four dollars and change, if I bought eight images. The photo had been posted by someone called Renzzo, who had uploaded 554 other images to the site.

I still wanted to know more about it. It was harder than I had thought it would be to reach the hotel by email: I filled out a form and then received a series of automated messages that someone would get back to me, and eventually someone did get back to me. I told them that I wanted to know where the picture had come from and how they had chosen it and that I wanted to write about it. They did not get back to me again. My friend Renzzo, also, did not have an easily findable email address. I contacted Dreamstime and asked them to pass along my contact info; they said they would, but also suggested that I leave a comment on the image itself. I did this, but did not hear back. That was OK; I didn't mind the image exactly as it was, straight from the frictionless void of the business hotel, without the aid of human intervention and without requiring, in return, any human attention.