Last Monday, Donovan Mitchell gouged the Bulls for 71 points, the highest total in the NBA in 17 years. Mitchell's bedraggled Cavaliers needed every last bucket he could give them, as they trailed by 18 at halftime without two of their best four players, though for a 71-point explosion, it was unnervingly reasonable; normal, even. This was not like Kobe Bryant's 46-shot 81-pointer in 2006, or Devin Booker's futile 70-spot in 2017. Mitchell notched 11 assists, and as his coach said after the game, every play he made was correct and necessary. If it's possible for a 71-point game to feel like the result of a game's natural rhythms, to feel normal, well, this was the one.

I say normal because on the very same night that Mitchell scored 71 points, Klay Thompson had 54 points against the Hawks, LeBron James put up 43 against the Hornets, and Joel Embiid slammed 42 on the Pelicans. Even the keenest-eyed of NBA fans could be forgiven for overlooking DeMar DeRozan's 44-point showing in the very same game Mitchell scored his 71. Perhaps the most intriguing league-wide trend of this NBA season has been the accelerating proliferation of huge single-game scoring numbers. After Sunday's games, 34 different players have scored 40 or more points a total of 91 times. The season is not yet halfway over, and if the current rate of monster scoring games continues, we are on pace for 185 such games, which would be by far the most in any season in NBA history.

Anecdotally, it feels like someone is destined to put up a monster performance every night, to the degree that something like the median 40-point game (Tyrese Haliburton's career-high 43-point, seven-assist night on Dec. 23) doesn't really stand out. Someone from 23 of the league's 30 teams has eclipsed the 40-point mark, and five pairs and three trios of teammates have done so (once, for Caris LeVert and Darius Garland, in the same game). Jan. 2, when Mitchell hit 71, marked the third time in 11 days that five different players exceeded 40 points on the same night. Even in the modern era of unprecedented offensive potency, these numbers are stark outliers. Whether you find the nigh-uncountable flock of 40-pointers annoying or thrilling, there is clearly something going on here.

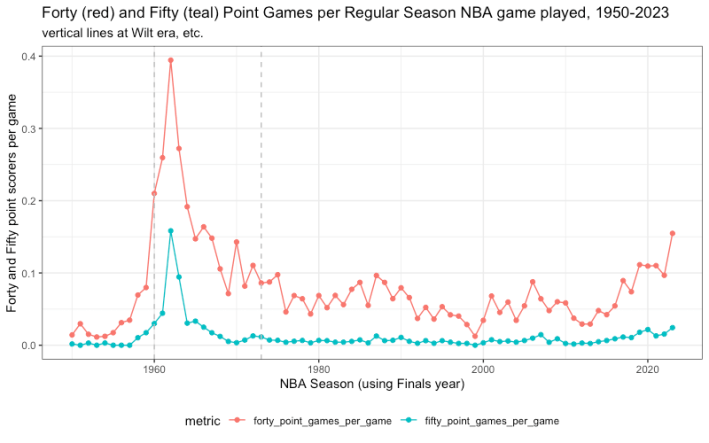

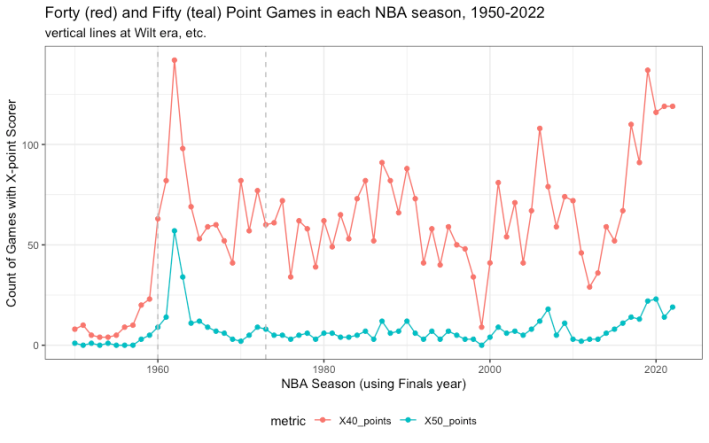

When considering the history of 40-plussers, the first and most meaningful distinction to make is between the Wilt Chamberlain era and, well, everything else. Chamberlain racked up 40 or more 271 times in his career, which is nearly three times the total of 40-spots (98) in all of pre-Wilt NBA history. The current high-water mark for 40-pointers is the 1961-62 season (142), when Chamberlain averaged 50.4 points, scored his 100 against the Knicks, and played every single minute of the season except for an eight-minute stretch of a game against the Lakers where he was ejected, somehow allowing him to average over 48 minutes per game. Because there were fewer teams and fewer games on the schedule back then, the degree to which Chamberlain's presence warps the 40-point games per game chart is pretty hilarious.

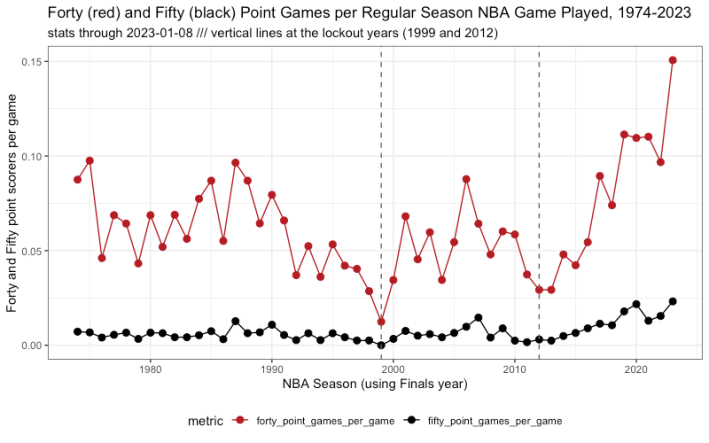

Aside from a few outlier Chamberlain years, the number of total 40-spots fluctuates within a reasonably constrained band until around 2015, when Bay Area-based alchemists hit upon a startling discovery: numerically speaking, three is 50 percent larger than two. After the two-year time lag it took for the ramifications of this thesis to make their way through the towns and burgs of North America, the number of 40- and 50-point games exploded. The following chart shows the raw totals per season, through the end of the 2021-22 season.

Clearly things have been ticking steadily upward since the recent low 10 seasons ago, when only 36 players notched 40. Steph Curry posted that season's high of 54 points, an ominous sign for revanchists whose brains short circuit when someone shoots multiple three-pointers per game. This year's per game numbers, however, show a huge spike. So, why?

The first and most obvious explanation for this phenomenon is that teams are scoring more, and more efficiently than ever before. Points-per-game peaked during the Chamberlain era, though the number is starting to climb back up. This current season is on pace for the highest offensive rating in NBA history by a full 1.3 points, though unfortunately, the first year that Basketball Reference has offensive rating data for is the first post-Wilt season, so we don't have a per-possession marker of just how thoroughly Chamberlain was clowning all the milkmen and factory workers of his day. One of the most obvious and significant changes to the NBA meta-game has been the omnipresence of the three-pointer in every single team's arsenal, though a strange wrinkle is that this season's three-point percentage across the league is 35.7, only 15th-best in NBA history. Pace is up a little bit, effective field goal percentage is at an all-time high, and turnover rates are a tad higher than last year's all-time low, yet none of the team offensive statistics adequately explain why we could end up with significantly more 40-plus point games this season than we did in 1961-62.

I think the best explanation for why so many dudes are having huge scoring nights almost every night begins with the Curry-led adoption of the three, in the sense that basically every team plays four- or five-out basketball now and builds their offense around quality spacing. More space on the court and smaller lineups built to create and take advantage of all that room means fewer shot-blocking menaces at the rim, more room for superstar players to engineer shots for themselves, a much more spatially demanding job for defenses, and, I think most crucially, harsher consequences for sending help. Luka Doncic's game is a clean way to understand that last bit, as the Mavericks offense is built, to a hilarious degree, around Doncic's ability to cook anyone in isolation or find the correct pass when teams inevitably decide they've had enough of him roasting even their best one-on-one defender. Let him go, and he'll destroy you by himself; send help, and you cede like 12 wide-open three-pointers to a group of shooters whose only job on the floor is to prevent you from helping too much on Doncic.

Doncic is far from the only player to take advantage of such a situation. The average highest usage rate for every team's most utilized player is way up this season, which I would argue is a direct consequence of the coeval evolution of NBA offense and defense. Defending a team that plays five-out with a superstar running the show is incredibly difficult, as all five defenders must execute a series of flawless rotations as a unit, covering way more space than they had to a decade ago. Having one or two great wing defenders doesn't matter if every opponent can pass the rock fast enough to punish one missed rotation. The usage numbers (and, more importantly, the basketball on my screen) suggest that teams help way less so as not to give up a million threes, and thus, Lauri Markkanen gets to drop 49 points on five dribbles on the Rockets because he only ever has to shoot over one guy.

Steve Kerr's theory rhymes with mine, though he emphasized that transition defense is really bad right now. That makes sense, given both the new take foul rule (which has boosted scoring) and the novel difficulties of defending in transition in the new spacing regime. Offensive players are out on the perimeter more than ever, but so are their defenders, who are way closer to their basket and have less distance to sprint into for transition buckets. Maybe this schematic wrinkle is less widespread than I think because I watch Domantas Sabonis get defensive boards and manufacture a thousand transition looks in every game, but Kerr's take seems true to me.

Huge individual scoring nights are up across the league. Six guys are averaging 30+ per game. Steve Kerr gives his thoughts on it. Believes NBA skill/shooting is better than ever, but defensive foundation has trended down. “Transition defense is at an all-time low.” pic.twitter.com/6yfZQj6j8E

— Anthony Slater (@anthonyVslater) January 5, 2023

As Lev Akabas pointed out, the league's move towards this style of basketball has raised the floor for offensive efficiency and brought the league's 30 teams into a pretty tightly grouped bunch. The other major league-wide trend this season, which I think is conjoined with nutty individual performances, is parity. There are only five true poo-poo toilet teams, and even the 10-30 Rockets have beaten the Bucks and Suns (twice). A downstream consequence of parity is more close games, and as Seth Partnow wrote in his newsletter last week, closer games mean superstar players are taking more shots later in games. There is less garbage time this season than in years past, and as the Russellian theory of buckets holds, crunch time is when superstars feast.

Isn't that what fans should want? There's been some grumbling about how the seeming ubiquity of 40-plus point performances is boring, devalued, impossible to keep up with, or is a fake byproduct of the league making it illegal to play hard-nosed defense. I like watching the NBA because I like watching the best basketball players in the world do battle against each other and push the boundaries of athletic possibility. The NBA is, more than any of its competitors, a star's league. Maybe even that designation seems devalued when, say, Tyrese Maxey can simply make nine threes in an otherwise unremarkable October win against Toronto, though I think the league is more fun to watch when a larger number of players are capable of scoring a bucketload of points on any given night. That said, I will probably disavow this take after I have to watch Cole Anthony make 10 three-pointers against the Kings tonight.