Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on April 5.

“Analytics is an arms race to nowhere.” According to Evan Drellich of The Athletic, this was the verdict of an anonymous franchise owner in MLB as relayed by MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred. The fact that the commissioner is opining on the state of analytics in the game speaks to how a once-marginalized group of outsiders has become one of the dominant forces in the game. But there is an uncomfortable truth in the statement, mixed metaphors aside. The unnamed franchise owner went on to say that the pursuit of small strategic advantages has led to some teams grabbing those advantages in the short term, but in a copy-cat league, it quickly breeds a sameness; because everyone has taken advantage, there’s no further edge to be had. Plus, there’s the ever-present concern that the league is being pushed toward a brand of play that just isn’t as much fun.

The NFL and NBA have gone through similar reckonings with mixed results. Analytics in the NFL showed that the traditional “three yards and a cloud of dust” approach to the game wasn’t ideal, and through a series of rule changes and evolutions, the game has become more pass-friendly. The fans like that. In the NBA, the realization that three is greater than two has led to a game dominated by the three-point shot. Fans apparently have mixed reactions to that.

It is unquestionably true that gameplay in baseball has changed, even before the new rules came into effect. The game has wobbled all over the place through its history, but it is correct to blame at least some of the new wrinkles on analytics. But if we’re going to play the blame game here, the details really matter. It’s the sort of thing that I could write an entire book about.

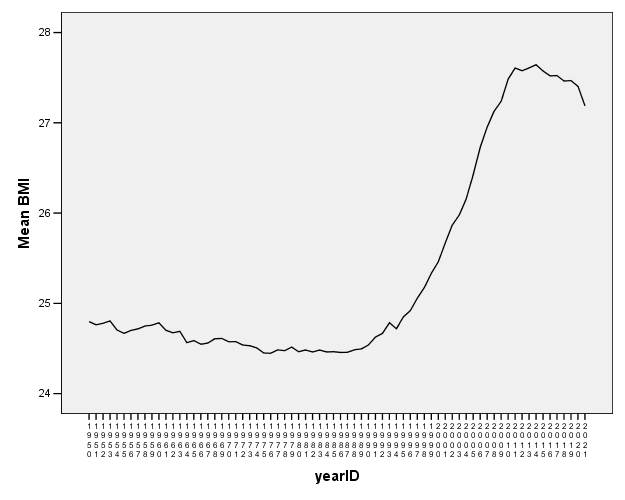

If we really have reached Nowhere, let’s talk about how we got here and start with the fact that some of the forces acting on baseball have nothing at all to do with analytics. For example, players are larger today than ever.

That’s the average Body-Mass Index of all players in a given season. Players can throw harder, they hit the ball over the fence more often, and they run less often than they usually do. Some of that might be changes in approach, but some of that is just physics. When you change the inputs into the game, you’re going to get something that looks different than it used to. Faster fastballs are harder to hit.

But here’s a chart showing the distance between the bases as well as the distance between home plate and the pitcher’s mound during that same time period.

There are some pieces of this puzzle that are ground truths, that you can’t do anything about unless you plan to incorporate speed limits or size limits into the game. In these cases, analytics is really only there to catalog what happened and make a graph about it.

At this point, it’s trite to say that you can’t ban knowledge or people trying to win. That’s true, but there’s no one who would reasonably argue against that. Teams want to know the best way to win the at-bat or the game or the pennant. Over 150 years of baseball, people have tried different ideas and some work more often than others. Sometimes, someone comes up with a new one. It is true that at this point, all 30 teams have a small phalanx of people who look through the data to find that edge. Some of that has produced an “arms race to nowhere.”

I think the frustration around analytics was that people assumed that there would always be a counter-balancing factor. For example, as the infield shift gained prominence—and honestly, preeminence—within the game, there was an assumption that batters would make a counter-move and begin hitting to the opposite field. “The pendulum always swings back” they would say.

There are cases where things self-correct when someone has gone “too far” to one side of the pendulum. Suppose that I had two choices in a game, left or right, and that I could pick either at will. If I’m constantly going to the right, my opponent will defend me accordingly and it would make sense for me to start going more to my left. Eventually, my opponent will figure that out, and the system will swing back, and over time, there will be some right, some left, and everything will end up in a bit of a standstill. But it would be a mix of both the left and right strategy.

Not everything works like that, and if there’s something that we’ve found out about baseball, it’s that it’s not structurally set up for those sorts of self-corrections. With the infield shift, what we saw was that while the shift was originally reserved for hitters who pulled the ball “a lot,” the definition of “a lot” kept sliding further toward the short end of the dial. Particularly for left-handed batters, the benefit that teams got from stationing a third defender on the right side of the infield was much greater than the hit that they took by leaving the left side unguarded, and just about everyone pulls enough to make it worth their while.

Add to that, when teams shifted batters to pull, they also pitched the batters to pull. And when batters hit the ball the other way, they didn’t get quite as much oomph on it as when they pulled, and it’s the exit velocity that had a bigger impact on whether or not the ball would go for a hit. There wasn’t a force that would pull batters away from pulling. MLB’s only recourse was to ban the infield shift. Or let it take over the game. The infield shift was the counter-move. Teams probably should have always been playing that way.

Once teams had that knowledge, we certainly can’t expect them to ignore it.

Maybe analytics is an “arms race to nowhere,” but I’d suggest that the most powerful force in Nowhere, the one that will separate the winners and losers in the analytic movement, isn’t the size of a team’s supercomputer or the number of analysts they have on staff. It’s the coefficient of friction in the organization.

It’s a reality that teams are able to identify advantages using analytical approaches. Over time, I’ve previously found that it takes about 10 years for a strategic innovation to saturate all the way through the league. Once someone has found the edge, it’s not easy to keep it quiet. It might be playing out right there on the field and even if it’s not, baseball people like to talk. Of course, if it were just as simple as identifying an edge and then implementing it, it wouldn’t take 10 years. There are some teams that lag behind, either in seeking out those edges or because they hold back when they learn of them. Sometimes it’s pride. Sometimes it’s lack of agility. Maybe it’s a little of both.

It’s an arms race, and some folks aren’t very fast.

The smartest teams aren’t necessarily the ones who find the #NewMoneyball. They’re the ones that can recognize an idea, even if it was brought forward by someone else, and get past the inertia to put it into effect. Eventually, everyone else is going to get there too, and you need to take advantage of the lag time that inertia grants you. It isn’t a specific innovation that wins it for you. It’s the willingness to step out ahead of the pack and grab the advantages out there while you can. That’s not going to be comfortable because it puts a premium on change in a sport that has always held (the illusion of) consistency dear.

We are in a time of turmoil in MLB. We now have rule changes that are being used in games that count, and some of them were borne of the realization that there was no self-corrective mechanism built into the game to deal with some of the problems that had cropped up. I realize that people have some big feelings about many of the issues. You can’t pin all of baseball’s problems on analytics, but there’s no denying that over the last 25 years, we’ve gathered together both the data sets and the capabilities to analyze the sorts of questions that have led to some of those problems.

I do think that no matter your views on the pitch clock or the ghost runner, there needs to be a reality check. If there’s a loss of innocence that we’ve all gone through in these past few years, it’s the loss of the idea that baseball is somehow a self-correcting system that would figure out a way. That it was somehow a blessed game. It isn’t. Structurally, baseball has some dead ends, and we have found a few of them over the past few years. MLB has responded by changing the very structure of the game in response.

But there has to be a reality check somewhere in here. Baseball is a game that, left to its own devices, will spin out of control at times. Even with a firm hand guiding it, there’s still going to be more wheel-spinning to come. Trying to shape baseball into a more aesthetically pleasing form is going to be bumpy. You can’t turn off people looking for competitive edges. You can’t turn off the outside world. And there are going to be more moments where you have to choose between changes to the fabric of the game or a version of it that is organic and a little misshapen.