This excerpt from Pete Croatto's new book From Hang Time To Prime Time is published with the permission of Atria Books/Simon & Schuster.

Sneaker companies did not attach a player’s name to a shoe, save for two notable exceptions now part of sneakerhead lore. There was the stylish Adidas Jabbar, first released in 1978, which found an audience among hoop fans and hip-hop heads in New York City.

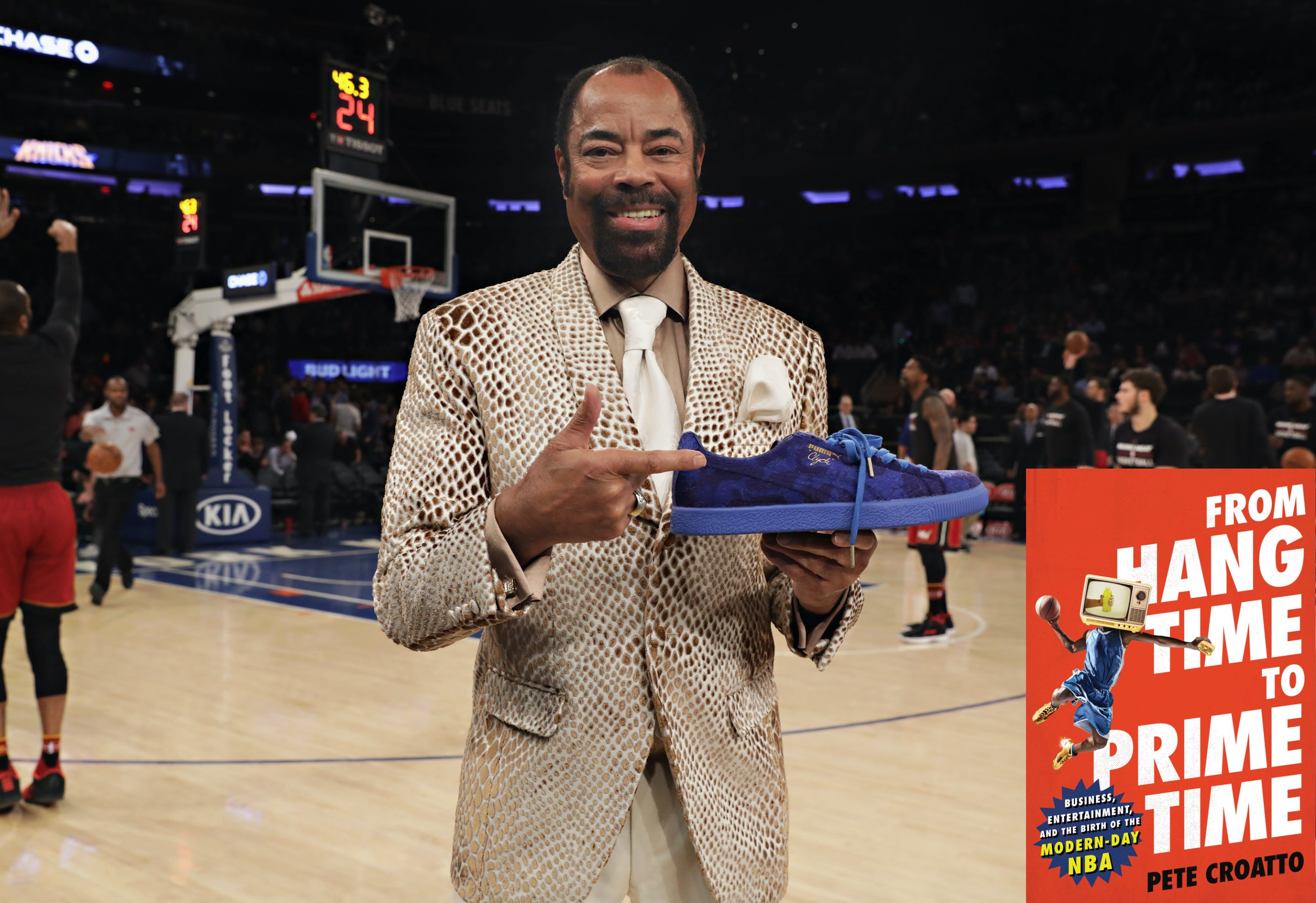

Walt “Clyde” Frazier was the first basketball player to have his own shoe when the colorful, suede Puma Clydes strutted into stores in 1972. There was little pomp and circumstance to the arrangement. Bill Mathis, a former New York Jets halfback and a Puma rep of sorts, arranged the meeting. Frazier was offered five thousand dollars and shoes galore. He signed the sneaker deal not to enhance his already groovy legacy, but for the money.

Puma’s first attempt at the shoe was a disaster, clunky and heavy. Frazier suggested some modifications. The shoes sold out in New York, Connecticut, and New York—the Knicks’ tristate area of fans. They were so prized that some inventive admirers wore plastic bags over the sneakers to keep them dry. Frazier saw the impact where it mattered most—his paycheck. He got twenty-five cents per pair of shoes sold, an arrangement that landed him hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Younger basketball fans know Frazier today as the Knicks announcer who puts the color in color analyst with his ROYGBIV suits and rhyming, polysyllabic vocab. Decades before he was “dishing and swishing” and inadvertently teaching SAT words, Frazier was the NBA’s first superstar of style and substance. “The idea of the basketball player as a style icon, Clyde absolutely created that,” hip-hop journalist Nelson George said. In today’s NBA, where the players’ pregame amble to the locker room has become a nightly catwalk, Frazier was Twiggy with muttonchops. He didn’t take his wardrobe cues from GQ, but women’s magazines. “You see so many more different styles with the women,” Frazier said.

Frazier was a star for the storied, endlessly chronicled Knicks teams that won two NBA championships in the early 1970s. But so was Bill Bradley. So was Willis Reed. Frazier stood out because of his on-court style, thought Marv Albert, the team’s cherished broadcaster. If he was knocked down, no matter how hard the shot, he took his time getting up. “Cool I think is reactions, reflexes, and attitude,” Frazier wrote during that time. “You got to feel out the situation. You can’t be out of control. I think I’m cool—most of the time.” That applied to getting hit in the chops. If the other team saw how much pain he was in, it would take advantage.

The stoicism did not apply to his fashion sense. He wore—amid nonstop mockery—wide-brimmed, velour fedoras well before Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde turned the item into pop culture ephemera. When Knicks trainer Danny Whelan dubbed Frazier “Clyde,” he didn’t shrink from the moniker. Frazier embraced “sartorial splendor”: the mod, perfectly tailored suits, the Rolls-Royce with WCF license plates, a bedroom dominated with silk, shag, and a nine-foot round mirror on the ceiling. He had such a rapturous work-life balance that he wrote a guidebook (Rockin’ Steady) on how he achieved that. The shoes— which Frazier wore on the Garden floor—got you a step closer to being Clyde. Frazier’s fame came when pro athletes didn’t shroud their social lives in high-priced secrecy. He took the subway to Madison Square Garden. He inhabited a world you knew, but like Joe Namath, Frazier grabbed New York City by the haunches. John C. Jay, later Wieden + Kennedy’s creative director, remembered sitting at a club in the Upper East Side on a slow Sunday night. That burgundy and antelope RollsRoyce pulled up. Frazier scoped the room and sat down next down to a beautiful woman at the bar. Fifteen minutes later, Clyde and the lady departed to the double-parked Clydemobile.

As Puma attempted to put you in Clyde’s world—and good luck with that—Nike helped turn sneakers into casual wear in the mid-1970s. After the waffle trainer—affordable, with a splash of color—was offered in blue to pair better with jeans, “we couldn’t make enough,” Phil Knight recalled. Americans, thought John Horan, the founder of Sporting Goods Intelligence Magazine, started to dress less formally. Baby Boomers started to get into fitness—The Complete Book of Running, Jim Fixx’s huge bestseller, was published in 1977. Nike, he said, grasped the changing American lifestyle. Sneaker historian Bobbito Garcia noted that sneakers as an everyday accessory sprang from 1950s American youth culture. “Casual dress became desired and its acceptability was unprecedented,” Garcia wrote in his fascinating chronicle of New York City’s sneaker culture, Where’d You Get Those? “Sneakers were no longer just gym class shoes, but the preferred choice of kids everywhere."

Around the time more Americans wore sneakers to Pathmark or to class, the footwear became an integral part of the hip-hop wardrobe. The style became “fresh out of the box”—clean. As rap worked its way onto MTV, kids did more than copy what they heard. They had constant exposure to a look, one that was relatively easy to emulate, if they weren’t already doing that. “What we wear onstage is just what all the youth wear,” said Darryl “DMC” McDaniels. “So dressing this way lets them know, ‘Oh, he’s just like me.’”

When Run-DMC performed “My Adidas” at Madison Square Garden on July 19, 1986, and asked the crowd to lift their Adidas in the air, thousands responded. It was an historic and predictable moment. After he caught Run-DMC’s performance at the Garden, Adidas executive Angelo Anastasio urged company founder Horst Dassler to sign the group to a contract. (Run-DMC famously wore Superstars, but Garcia writes that Jabbars started the hip-hop community’s loyalty to Adidas.)

“Almost incidentally, if you achieve that kind of prominence in American life, you’re going to achieve it for whatever it is you’re officially doing, but also people are curious,” said Bill Adler, a longtime executive at Def Jam Records and a hip-hop historian. “You do this work, and your work wins applause, then also they want to learn about the person. And among the things they’re going to look at is the clothing.” In this case, Adler said, it was the Superstars—Jackie Kennedy’s pillbox hat for the MTV generation—and how Run-DMC rocked them without laces. Jam Master Jay, the group’s DJ, started it. According to Adler, prison inmates couldn’t wear sneakers with laces because they could become weaponized. After some of these men were released, they kept the look. Jay adopted this aspect of “Queens street hustler style” and inspired a pop culture moment.

Fashion trends, said Logo 7 founder Tom Shine, don’t come from Scarsdale. Sneakers had always been an integral part of hip-hop culture, said Sean Williams, the sneaker historian. Music was one part. “It’s graffiti, it’s DJing, it’s B-boying, and one of those elements that doesn’t get spoken about a lot is knowledge and passing it on, and mentorship,” he said.

Again, an element of rebellion was commodified and turned into fashion, like the leather jacket. As Williams said:

Sneakers were part of the official hip-hop uniform, because they represented anti-establishment. That’s why sneakers were chosen as part of the hip-hop uniform; there were so many places you couldn’t go wearing sneakers. They were a marginalizing thing. You were deemed as someone less likely to succeed if you wore sneakers all of the time. You couldn’t wear them in churches; you couldn’t wear them in certain restaurants, you couldn’t wear them in clubs. There are so many places— you couldn’t wear them at work. So anything anti-establishment was going to gravitate toward that. So when hip-hop culture was being established in the ’70s, they were like “Yeah, we wear sneakers; we could give a shit about going to your establishments—your churches, your clubs, your workplace.” So that’s why you hear a lot of genuine hip-hop people, like myself, who say, “Hip-hop really is a lifestyle; it’s really not just the music.”

Years after its initial release, Frazier heard stories of rappers and break dancers asking for “Clydes” who didn’t know who “Clyde” was. It would take a couple of years after Run-DMC’s capitalistic triumph for hip-hop and sneakers to enjoy a mainstream marriage, a development that involved a couple of contrarian acts that immediately sprang a nation into commerce-driven cool.

Frazier wouldn’t have minded one bit. He was the pioneer. When he attended an event at Puma’s headquarters in Germany decades after his shoes hit the street, Frazier came onto the stage unannounced. The crowd unleashed a five-minute-long standing ovation for the man whose shoe his grandchildren were once embarrassed to wear.

The speaker (via phone) who preceded Frazier: Jay-Z, the man who had turned retro basketball jerseys into high fashion.