For as long as companies have manufactured and sold baseball cards, they have screwed up some of those cards. There are just too many players and too many cards for it to have gone any other way, and for a very long time there was also no meaningful quality control to speak of. The shadowy prehistory in which it was authentically very difficult to know with any certainty the sort of insignificant things that are highly significant for creating a non-embarrassing trading card is just a few generations in the past. The game of baseball was, for a long time, bigger than any institutional capacity to contain or commemorate it on the part of the companies that made and sold its trading cards. It showed, fairly often.

If Claude Raymond wanted to pose with his fly open in two consecutive Topps sets, or if Gary Pettis wanted to send his 16-year-old brother out to get his picture taken for him, or if right-handed pitcher Lew Burdette wanted to pose for his card as if he were a left-handed pitcher, there was only so much that could or anyway would be done about any of it. The business was very profitable, and there was no meaningful competition or accountability or reason to do better. The cards looked as good as they did because Topps employed brilliant designers; they were goofy in the ways that they were because those areas weren't a priority.

It either is or isn't surprising that much of this period was objectively a golden age. Everyone was doing their jobs as well as they could and, while only some of what that produced was any good, that has also always been true of every golden age. Throughout the 1950s and '60s Topps rolled out sets that remain iconic triumphs of graphic design, albeit ones built around photos of squinting, pickled-looking men grimacing into the middle distance, all of which seemed to have been taken during the same few hazy days of spring training. Some of this couldn't be helped; it was a moment in which even professional athletes all looked like either gormless 13-year-old farmhands or exactly like Lyndon Johnson, and also in which action photography was too expensive and difficult to appear on trading cards.

This golden age, then, was at least in part an accident, or a coincidence. The cards from that period—and from the earlier one in which cards were tiny fragile reproductions of painted portraits packaged with tobacco—didn't know or care that they were also art that people might someday find valuable. They were, it turned out, but that they were art had nothing to do with them later becoming so valuable. When the first big baseball card boom came, it was all about scarcity—the overwhelming majority of those cards wound up in the trash, and the ones that survived that culling and the intervening decades had in most cases been treated not like art but like replacement-level bookmarks, which made the well-preserved ones all the more precious.

The level of craft and care that went into these cards, which became blue-chip collectibles three decades ago and have only appreciated since, was both significant and mostly incidental to their value. This is a useful reality check when it comes to comparing those cards to the ones that came after, first during the glutted slipshod boom of the 1990s and then the more optimized trading card boomlet of this moment. When I asked the collector and friend Jeff Katz for his thoughts after Topps rolled out a pyrotechnically defective set of Topps Now cards that managed to jam both copious glaring factual errors and some objectively lorem-ipsum prose into commemorating Atlanta's World Series win, he responded to my sense that those cards signaled a sort of divergence with the past by sending me the back of a card produced during the company's golden age.

It was one of those split Top Prospect cards, from the 1964 set. One of those prospects was Rick Wise, who would go on to make a couple of All-Star teams over a long and distinguished big-league career, but it was decidedly a common card. Katz had helpfully circled the text dedicated to the other player on it. "Dave is the younger brother of the Phils' ace Dennis Bennett," it read. "The 19-year-old righthanded curveballer is just 18 years old!"

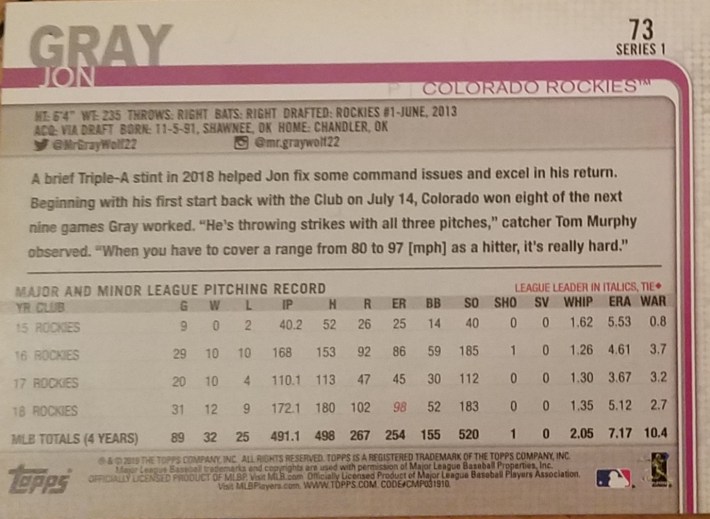

While all the cards mentioned above have mistakes on them, they're not Errors in a way that matters to collectors. That is, they were never pulled from production and replaced, or fixed in any way. They are every bit as common and so, in that sense, exactly as worthless as any other card. This stuff still happens, because there are hundreds of cards in each set and many different products, and also because only so many people will ever care. A handful of cards in Topps' flagship baseball set in 2019 ascribed devastatingly and very obviously incorrect career statistics to a few unlucky players; a disproportionate number of these players, in a neatly tragicomic twist, were pitchers for the Colorado Rockies. A reader sent me an email about this at the old site, I bought and opened a box, and found ... some weird cards that vandalized the career ERA and WHIP lines of Chad Bettis and Antonio Senzatela in weird, rude ways, but which no one really ever noticed, let alone cared about. The front of the card is and has always been the thing, and these were the common cards of unremarkable players.

And yet it must be said that these cards are also carefully made. The text on the back is informative and correct; it was written by Bruce Herman, who writes virtually every card Topps publishes, and who was my editor for a couple of years after I left my editorial job at Topps and started writing card backs. The pictures on the front are colorful action photos, tweaked mildly into strangeness such that the Rockies' purple jerseys glow like ripe Concord grapes. Everywhere, including in those few duffed stats—I found fewer than 10 such cards in the whole set—there is the sense of a human fingerprint. Someone tried to make even these most common cards memorable. For some players, it might be the only one they get.

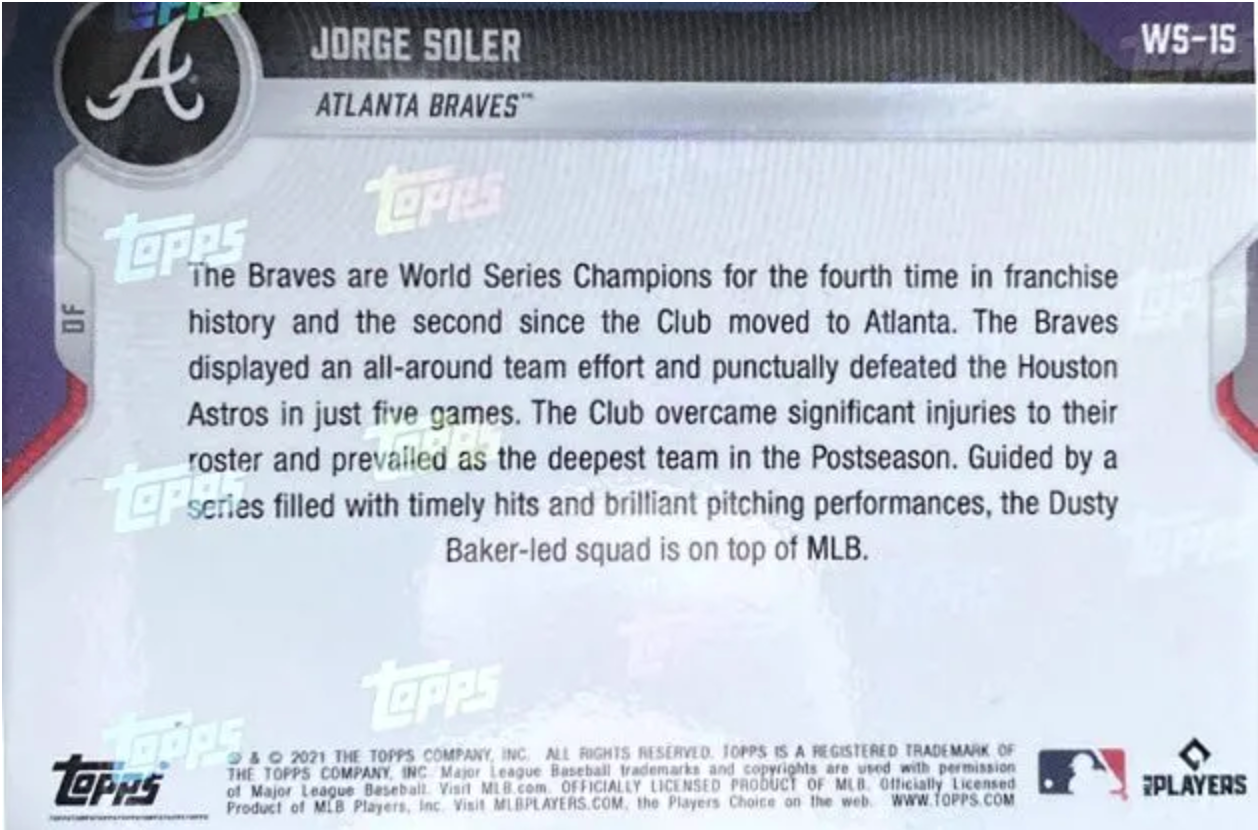

The way in which those embarrassingly incorrect Topps Now cards were wrong, by contrast, demonstrates the opposite. Herman did not write them; given what Topps Now is, the usual editorial timeline wouldn't work. Topps Now cards are pegged to specific moments in time—a Major League debut, a celebrity first pitch, whatever Topps determines collectors might want to buy—and are only for sale for 24 hours, and only the number of cards bought during that period are ever printed. The World Series set, which celebrated Atlanta's win by misidentifying their manager as Dusty Baker, misstating the number of games that it took for the team to win it, and adding some Trumpian crypto-Germanic capitalization to the mix, featured the same text on the backs of all 15 cards. When collectors complained, Topps swiftly apologized for the error and said that it would issue corrected cards to everyone who bought the 15-card set. The lavishly duffed original version will become an error card in the sense that it is corrected, but the corrected cards will not be more or less scarce than the originals. Call it a wash.

@DOBrienATL @grantmcauley just got my 15 card topps World Series set in the mail. Notice anything weird about the back of the cards? @Topps pic.twitter.com/0XiPfYJqRK

— Nick Wilson (@NickWilson38) December 13, 2021

They look fine on the front, I guess, though that's not quite the point where Topps Now cards are concerned. Because Topps Now cards will never be printed again after that initial 24-hour period, demand has a lot to do with future value. "You want a card that marks an event of sufficient importance that will seem important to collectors years down the line," a delightfully written June 2021 post at the website Cardlines writes. "But does so without attracting too much attention and driving up the print run. Therefore, getting a good Topps Now card requires prescience verging on clairvoyance."

The more scant the interest in that initial and final public offering, the more scarce the card will be, with various random parallel versions being scarcer still. The Cardlines post mentions that a 1-of-1 parallel commemorating Dr. Anthony Fauci's disastrously duffed first pitch at a Washington Nationals game sold for $10,000. In its meta-abstraction and institutional randomization, these cards seem about as close as baseball cards, perhaps the quintessential American fungible token, have come to NFTs. The future of the company will probably look a lot like this.

I was laid off by Topps in 2007, around the time that the company was sold by the Shorin family, which had founded it nearly 70 years earlier, to a group of private equity buyers headed by former Disney CEO Michael Eisner. There had been ups and downs under the Shorin family's stewardship, with Topps going public in the 1970s before being returned to private ownership, thanks to a leveraged buyout in 1984, that left the Shorins in charge. Around the time I was laid off, Topps was the subject of a struggle with another private equity group that had a share in the company, which wanted Topps to sell its candy division. (Topps makes Bazooka bubblegum and Ring Pops, which were always in great supply in the otherwise distressingly normal offices in Lower Manhattan.)

None of this was really very interesting to me even when I was employed there, which along with my powerfully on-brand decision to tell a higher-up in an interview that I was honestly not really interested in moving up the ladder probably had something to do with me getting churned out. It was fine. I started writing Topps cards for Herman just a short while later. That gig had the strange effect of rekindling my interest in cards. I wrote rookie cards for Kevin Durant and Greg Oden, then used a portion of my paycheck to buy boxes of those sets online and hunt for the cards I wrote. The phrase "hustling backwards" was not yet in common use, to be fair. The next collecting boom was still nearly a decade away.

Given that the current bull market in baseball cards has been inflated in part by high-profile rise-and-grind types boosting cards as flippable commodities, there's a sort of bleak irony in the fact that Topps was first hobbled and then purchased by one. Last August, the apparel company Fanatics, which is owned by the highly public entrepreneur and 76ers co-owner Michael Rubin, signed a licensing deal with Major League Baseball that effectively froze Topps out of the baseball card business. This left Topps, which was preparing to go public through a SPAC at the time, effectively dead in the water until Fanatics purchased it earlier this month for $500 million. "Fanatics’ plan for the physical trading card space is to expand it by opening the market to leverage it more via direct-to-consumer offerings, according to people familiar with the matter," CNBC reported in September. "For example, should collectors purchase a trading card, they’ll be able to insure the asset, grade, store, and even put them on a marketplace to sell or trade—all through Fanatics. The company would likely collect transaction fees, and leagues will also get valued data they crave." The story mentioned that Fanatics is also interested in getting into sports gambling, and noted that its private valuation was $18 billion.

There are reasons to be wary about this—here, for instance, is a hockey blogger who really does not think highly of Fanatics apparel—but more reasons to be simply weary of it. Purchasing Topps will enable Fanatics to make the actual cards that it will sell to collectors, although as is generally the case with Rubin, the story around it has been less about the things for sale and more about the relentless dealcraft and ambition pushing and pushing it all forward. The story is about growth, because growth is mostly what everyone involved cares about. The usual business-story signifiers all fall in their places; Forbes mentions Rubin's net worth relative to his peers at the end of stories about him in the same way that wire copy tends to note an injured or arrested player's batting average.

There is no real reason to think Rubin cares about trading cards beyond Topps' usefulness in his ongoing quest to become A Major Player wherever and whenever he can. But there is also no real reason to think it would matter if he did. The point my friend was making in sending me the text marveling at 19-year-old Dave Bennett being only 18 years old was one that I already understood, I think—that these cards have always been made by heedless capitalists in a hurry, but also that seeing value in a baseball card, any baseball card, was a choice that I made independent of any of the qualities that might otherwise make a card valuable.

There are many things like this; what you value beyond reason, or just above market, is part of what makes you who you are. These do not have to be, and really truly should not be, collectibles, but they are yours, and you carry them with you as you go through the world, and they inform the decisions you make. It's a tautology, in a sense, but in a way that runs counter to the broader cultural baseline—not valuing that which is valuable, but making things valuable through how much value you see in them. This is a crucial distinction, in this case, but also not one with much of a difference in it.

People naturally see value in different things, and value the same things for different reasons. Some people bought those Topps Now World Series cards because they wanted to remember Atlanta winning the World Series, and some just bought them to sell them again, later, for more money. None of that is wrong, really, though you can see how the people that made that decision for the first reason might be more insulted by how howlingly careless those cards were. In the long run, it is the nature of disruptors and disruption, and of the system in whose long shadow all this busy busy business gets done, to make things worth less. The shape of this has changed over time without the fact of it ever changing. The idea is to extract the absolute maximum, and the incentives all always run in that direction, and yet people still stubbornly find something to value in it. The care is squeezed out of all things as a matter of course, but somehow there's always someone there to catch it before it breaks, and take it home.