STAMFORD, Conn. — The Gary Lineker joke goes, “Football is a simple game. Twenty-two men chase a ball for 90 minutes and at the end, the Germans always win.” Perhaps it’s not the strongest analogy given the current state of Die Mannschaft, but the sentiment definitely applies to the last decade-plus of competitive crossword solving. Since the 2005 edition of the sport’s most prestigious competition, the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament (ACPT), was immortalized in the documentary Wordplay, only two people not named Tyler Hinman or Dan Feyer have won the A Final, the tournament’s highest level open to all competitors. Hell, only 14 different people have even made the A Final over that timespan, with just six names accounting for 44 of those 54 finalist slots.

But this year’s ACPT, held in a Marriott ballroom on April 5-7, featured a crop of contestants well-positioned to break Feyer and Hinman’s grip on the sport. Nearly all of the crossword community’s young guns and speediest online solvers made the trip to Stamford, and the old guard arrived knowing that solvers like Paolo Pasco and David Plotkin would be snapping at their heels.

Nearly two decades' worth of ACPT results made clear that any fresh-faced challenger had a long climb ahead of them. For the layperson, it can be hard to understand exactly how Hinman and Feyer have kept such a tight grip on the tournament for so long. We’re talking about a learnable skill with a low barrier to entry, and yet the distance between a top-100 competitor at the ACPT and someone like Feyer is not dissimilar to the distance between the best player at your local YMCA and LeBron James. Such a state of affairs fills the minds of both crossword novices and experts with the same question: How is it possible that these guys can finish a crossword in the time it’s taken you to read this far? Could someone like me, could anyone, do anything to beat them?

The main part of the ACPT consists of seven rounds. The first six happen on Saturday, the seventh happens on Sunday, and then the final round—played on large whiteboards in front of a crowd—occurs shortly after that. Solvers are given one puzzle to solve per round, and there are hundreds of people all working at the same time in the ballroom, like some kind of bizarro SAT testing center. Each competitor raises their hand as they finish that round's puzzle on paper, whereupon any of a number of officials standing around the room can collect their sheet and confirm their self-reported time against the many countdown clocks around the room (as every time is rounded to the minutes remaining on the clock, to-the-second accuracy isn’t necessary). Everyone is scored on those times and, importantly, a complete and correct grid: a single wrong square at the ACPT leads to an eight-minute penalty. With the tight margins of a crossword competition—especially at the very top—this is like penalizing offensive holding by chopping off a hand.

One silver lining for those of us who walk into the ACPT every year knowing that we have no shot at reaching the final is that we can dedicate more of our time and energy to enjoying the tournament’s social aspects. The world of constructors and competitive crossword solvers almost entirely fits comfortably into this one hotel ballroom. This closeness gives every crossword tournament, but especially the ACPT, the atmosphere of a small Shriners convention, or a very large family reunion, with the same collegiality and possibility for zaniness. (For example: At the now-defunct Indie 500 competition, one randomly selected solver won the opportunity to smash the face of the constructor of their least-favorite puzzle with a shaving cream pie.) For most ACPT attendees, the competition does end up as secondary: It’s a chance to see friends, rub elbows with the names you know only as bylines, and envelop yourself in the communal spirit.

This is what allowed me so much access to the top solvers, whom I could pepper with questions about what it actually takes to separate oneself and become a perennial winner. Feyer, a 46-year-old musician, plays the role of gracious elder statesman well. There’s a relaxed air about him, the kind that nine titles in 13 years affords you. “I don't have a regimen. I sort of keep up when I can,” he said, describing a routine of solving five to seven puzzles a day, with a growing backlog of 300+ puzzles. “I've found that if I can get through 50 to 100 puzzles on paper in the week or two leading up to [ACPT], then I can be in shape. So I do treat it like a sporting event in that I have to train my body, my eyes and my brain.” But he admitted that, despite having a track record that suggests he is in his prime, he sees the end coming. “Cognitively, my brain at 46 is not what it was at 32, just, you know, physiologically. I think I'm also slowing down a little bit, just like any athlete on the way down past their prime.”

Hinman, a 39-year-old software engineer, expressed a similar sentiment about keeping up with the growing number of speed solvers. “I'm good enough to make the final. I'm good enough to win the tournament. I won the title in 2022,” he said. “So, we're not really that far removed from it.” But with almost 20 years between this year and his first victory, he admitted to a slight downshift in his puzzle-solving regimen, one brought on by perspective and a knowing weariness. “I think I’m kind of good to just kind of see where the chips fall … maybe there'll be marginal gains from more training, but I also have a much more well-rounded life now and I try to keep that in mind.”

As for that next generation coming up behind Hinman and Feyer, the list of true contenders is short. On that list is Pasco, Plotkin, Erik Agard, and Will Nediger, who range in age from 23-34. “I know there are people who are definitely better than me at crosswords,” Feyer said. “Like all the time they’re better, not just at some time. You know, obviously Tyler can beat me and has, but Paolo, Erik, and Will are definitely better than me and faster than me. But there's never been more than one of [those three] competing with me at the same tournament. So if two or three of them show up, they should make the finals together.”

Pasco mirrored Feyer’s humility. “The problem with crosswords is you gotta know things, which I did not,” he told me, relaying the moment in middle school when he finally tried a crossword. “I know I don’t know a lot of things, especially compared to some of the other competitors. I’m, like, much less trivia-pilled than some of them.” A data scientist and recent Harvard grad, Pasco once solved a Monday New York Times crossword in 45 seconds. At last year’s ACPT, he came maddeningly close to winning the title, but a 20-second pause on his final square—an incredibly mean cross of two pieces of geographic trivia—swung the title to Feyer by a single second. “When I see geography stuff, my mind just goes to static,” Pasco said.

Plotkin, an entomologist who has amassed the most A Final appearances in the last decade without winning the title, is exactly who Pasco is describing when he jokingly talks about trivia heads. “Over the last three years, I have honestly probably put more time into trivia and quizzing than I have speed solving,” he said, likening it to killing two birds with one stone. “People who know me know that I talk about flashcarding non-stop because it's gotten to the point where most of the new facts I'm learning, I'm learning from concentrated study as opposed to directly engaging with material.” As an example, he points to the recent movie Barbie, rattling off 10 actors in the film and a list of associated memes—“I’m Just Ken,” “just beach,” Mojo Dojo Casa House—despite never having seen the film. But keeping up with the broad expanse of pop-culture knowledge has paid dividends. “The reps matter, knowing what is grid-worthy and what is not, and doing a wide variety of puzzles from different venues, from different constructors … being prepared for all those eventualities is important.”

If Pasco and Plotkin came to this year’s tournament looking to break through, Stella Zawistowski, a 45-year-old advertising copywriter, could tell them how hard it is to take that last step to a title. Zawistowski has been a mainstay in the top 10 at the ACPT for the last decade or so, and yet she has never made it through to the A Final. “This is the hard part when you're like, I'm in this desperately frustrating area here, where I'm really fucking good, but I'm not quite as good as the very top people that keep winning this thing, right?” she said. “And so I don't know how to get from here to there. So you know, when I hear something that is new to me and sounds like it could work, yeah, I'm going to try it.”

It bears repeating just how fast the elite competitors are, even amongst the self-selected group of competitive speed solvers. One way to visualize this: At the most recent Lollapuzzoola, an annual crossword tournament in New York City, Nediger—the eventual Lolla champion in his first in-person tournament—finished the five preliminary puzzles in a combined time of 27:52, a full 3:28 faster than the tournament’s pairs champion (where two solvers work simultaneously on the same piece of paper). And it’s not like Nediger outpaced a pair of slouches: the father-daughter team who took the title, Pete and Claire Rimkus, placed 27th and 21st respectively at the 2023 ACPT.

The top solvers are light years ahead of the rest of us, and leagues ahead of other competitors. But for all but Feyer and Hinman, an ACPT title remains elusive. As Pasco told me, “Ever since last year, with the way it finished, it’s been full dedication, like running on a treadmill with no headphones in. I just want to win one, so I can chill a bit.”

After two puzzles, the standings are as expected. The fastest elite solvers finish a breezy 81-word puzzle in under three minutes, and then a tougher 87-word grid in under four. Pasco and Nediger lead the pack, with Hinman, Plotkin, Zawistowski, and New Yorker games editor Andy Kravis just a minute behind them. Feyer is in a tie for seventh, a minute beyond that. Stan Park, returning for his fourth ACPT after a decade away, sits in 19th, four minutes behind the leaders. Shannon Rapp, in her third ACPT, has a comfortable spot in the top 100. Your author, brain-wormed by talking to so many speed solvers, mucked the first and easiest puzzle by answering LEAD PIN instead of HEAD PIN on a bowling-related clue without checking the crossing (CLOSE/CHOSE). He sits in 263rd place.

Ask any solver what it takes to get better, and they’ll start with the simplest advice: Just solve more puzzles. Rapp, a research coordinator who started working with a crossword solving coach three years ago, meticulously tracks her solving stats in Excel. She estimates that she’s done about 8,000 puzzles over the last three years, including nearly 3,800 puzzles since the last ACPT. The regimen has certainly helped: In the span of a year, she went from the bottom quartile in her rookie ACPT to the top quartile. Park claimed that, including minis and midis, he solves upward of 10-15 puzzles daily. This number of practice reps is typical for the elite as well. As Zawistowski recalled, when she finally placed sixth in the early aughts, “I was really like, Oh my god, I really wanna win. And I think the following year, I think I did like 20 puzzles [on paper] a day for two months. All I gave myself was a sore hand.”

The biggest benefit of doing hundreds upon hundreds of puzzles a year is developing a strong sense of plausible or likely words based on letter patterns. Many solvers refer to this ability as a “Spidey-sense,” or a feel for the “puzzle’s vibes.” The biggest time suck on a puzzle, after all, is the act of going back and forth between the clue list and the grid, especially in a competitive setting where your clues aren’t served directly to you by an applet. Having a second sense lets you see an incomplete word slot with one or more letters already filled in and filter down what the possibilities are. This saves fractional seconds, which add up over the course of a solve.

“There's a lot to be said about vibing,” Pasco said. “When you do enough crosswords, you get a sense for what letters just feel right. So, if you're looking at a second row, and you’ve got two ideas for what an answer could be, and one is a lot of consonants, and one is a lot of A’s, I’s, O’s, and R’s, your mind leans toward that one.”

“My main thing is not really reading the clues, because reading the clues takes a long time,” Nediger said. “So you kind of get the gestalt of the clue, and look at the first few words and often that's enough.” He used the classic example of a four-letter word with a clue containing "cookie": “99 times out of 100, it’s going to be OREO.”

“David Plotkin famously has espoused the strategy … of don't check, miss as many clues as you can because every clue you're reading is taking you time,” Feyer said. “So if you can fill in things without checking the clues, as long as it has logical-looking crossers and corners, then that's the best way to go.” Feyer admits that despite his speed, he’s much more cautious than that. “I never look at a clue unless I have letters. So it's always based on what's there. That's the No. 1 tip I give for beginning solvers or people learning: Don't just page through all of the answers, which have no letters in there. Because the point of it, it’s a crossword. If you're looking at an answer that starts with B, then that reduces the possible answers to only that portion of your mental lexicon.”

“I play a dangerous game, despite my talk about being careful and fastidious,” Plotkin said. “I'm doing this because I'm also simultaneously trying to, in a devil-may-care fashion, minimize the number of clues I read. And what that means is not necessarily always reading all the down clues that are crossing the cross answer that I'm filling in, or vice versa.” He gave me an example, both of how this Spidey-sense functionally works, and how it needs to be constantly fine-tuned. “If I came across [a three-letter word] that starts with AY, I'm probably gonna immediately assume it's gonna end in an E for AYE, I don't need to check it … But now, [you have] AYO Edebiri, an Emmy winner. She's more than famous enough to be in a puzzle. And that shortcut, that one of the many thousands of shortcuts I think about or prepared to think about, no longer exists. When I say Spidey-sense, I guess what I really mean is recognizing letter patterns, knowing when there are multiple plausible answers that fit given letters that exist in the grid already, and knowing when it's important to check versus when it cannot possibly be anything else.”

Others have found a middle ground, after years of being burned by careless errors. “I've developed a habit of, during the puzzle, if something feels like it isn't quite right or I believe it's not, write it in—and Ellen Ripstein taught me this—just put a circle around that square to be like, Hey, come back to this later,” Zawistowski said. “But in general, I can trust that if I feel confident about a thing, it's almost certainly right. Like I've been doing this for enough years and my regular solving diet ... 61 times 52 is almost 3,200 puzzles a year.”

Taking this Spidey-sense and sublimating it into a nearly subconscious flow state almost always ends in a singular practice technique: downs-only solving. This is what it sounds like: only allowing yourself to view one set of clues. Downs are chosen because they’re infrequently theme clues, and thus are almost always real entries rather than, say, thematic puns. The idea is to use only your mental skill and knowledge of letter and word patterns to feel your way through the rest of the puzzle. Focusing on the downs is also helpful because rules of construction mean several down clues in a row will all be in one section of the grid and can therefore help you build a foothold, whereas across clues, when read in numerical order, by definition bounce across sections.

“At least for me, I learned the process for making guesses,” Pasco said. “Because you won’t have all the information, you’ll inevitably have to [guess] in downs-only solving. … Learning to be in a space of being stuck and also not freaking out about it is a really good skill.” When I joked with Pasco that this is all very funny coming from someone who can rip through a tough puzzle in under three minutes, he responded, “I don’t think I have any particular juice that makes it happen. For me, it’s just a process of doing it a lot of times until it becomes a fast thing, like muscle memory.”

But if all the top solvers have some kind of juice, are there other ways to steal precious milliseconds solving? Some of the top solvers swear by reading several clues at a time holding them in their mind as they move to the grid, in hopes of minimizing back and forth (especially if they’re downs). “Trip [Payne] told me that when he solves a large puzzle, he will read like five down clues in a row and then just drop them [in]. You know, like he has a good enough memory [to do that],” Zawistowski said. “I feel like I can do like two or three clues like that. And then it's easier to look at the next clue while you're still writing in your last answer.”

Plotkin offered similar advice, adding, “[it’s] almost like with video games. Because in many respects, the things that make professional gamers really good at what they do is not dissimilar to what speed solvers do. You need to be able to write without looking at your pen. You want to be able to know where your hand is, over the grid, and fill in the boxes without needing to look at it. Because while you're doing that, you want to look at clues.”

Heading into the notoriously difficult Puzzle 5, things become clearer. Pasco, Nediger, and Plotkin sit in the top three spots in order. The same trailing quartet (Feyer, Hinman, Kravis, and Zawistowski) are tied for fourth, just a minute behind Plotkin in third. Park is in 15th, nine minutes behind first. Rapp is in 90th. Your author has made up some time and has cracked the top 100.

Navigating the ACPT gauntlet also requires a feel for the pace of the competition. At the start, you need to be able to blitz through the easy puzzles in two or three minutes, but as the tournament drags on, you need to be able to reach into reserves of stamina and brainpower to crack the tougher puzzles within 10 minutes. Most of the top competitors come in with the same broad strategy: Keep pace with the peloton on the easy stuff, and don’t get broken by the dreaded Puzzle 5. Practice requires exposing yourself to not only the typical litany of national publications, but also drilling the more specialized, difficult puzzles out there, which are likely only recognizable to true crossword sickos. It’s in the hardest puzzles, when the difficulty ratchets up to “widowmaker,” where preparation can provide potential gains at the margins.

Pasco recalled a perfect example from a previous ACPT final: “I remember that David Plotkin got stuck in the south section on this three-letter answer with the clue 'Front,' and he had ?AN already. And as he hesitated for a while, I was sitting next to Joon [Pahk], who said, “Oh, I don’t think he’s solved a lot of the old [New York Times] stuff, because that’s the kind of stuff that always used to pop up.” The old stuff in question here is VAN, as in the prefix in VANGUARD, a clunkier and less elegant way to clue a three-letter word that likely wouldn’t fly in a daily puzzle for the masses these days, but is fair game for the championship.

“You can get faster only to a point. You can improve your times really fast at the beginning, and then you can improve it slightly, and it would be sort of asymptotic, kind of getting maybe a bit faster and faster,” Feyer said. “In terms of improving, I do think that you can continue to get better at hard puzzles, the hardest puzzles like the finals. Just more years of experience, more trivia, knowledge, just more exposure to all of the possible corpus of words that can show up in a puzzle.”

And sometimes, at the end of the day, it’s just luck. Feyer, a musician by trade, found some of that in last year’s final: “One of the [trickiest] letters, it was a letter in LINNET… that was a spot that other people had that they were questioning. And I was confident of that, thanks to Sondheim.” Pasco, reflecting on those same finals, also mused on the role of luck, likening it to his continued playing of lottery scratch-offs. “One of these times, everything will break right for me.”

Then again, many of the top solvers could recall with alarming precision at least one instance of a minor mistake on the easiest puzzles costing them the tournament, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a clean and correct puzzle alongside speed. “I think the easy puzzles in the tournament actually put a little bit more pressure on me than Puzzle 5 and the really tough ones, because those [hard ones] are just kind of wild cards. Like maybe I'll have a ton of trouble with it or maybe I'll latch onto it really quickly,” Hinman said. “But [puzzles] No. 1 and No. 4, there's a lot of pressure because they're easy puzzles, and with all the top competitors, you have to do this in under three minutes or you're going to drop time.”

Zawistowski recounted an even sillier mistake that cost her a top-10 placement. “I think it was 2021, I was so surprised not to hear my name announced for any awards, and then I ran into Brendan [Emmett Quigley], who's a friend and also a judge, and he goes, 'Yeah, you left two squares blank.' There you go. What the fuck? Yeah, I was pretty mad at myself … since then, now I do the thing where you look up and if you have time, you just do a quick scan. Did I fill everything in?”

Drama at the ACPT! As the returns from Puzzles 5 and 6 are uploaded, it looks for all the world that Dan Feyer has snuck back into the third spot on the podium. Pasco still leads the pack, with Nediger just a minute behind him. Hinman, despite the only sub-five minute time on the tricky Puzzle 5—this year, themed with the revealer NO SEE, with the conceit of the puzzle being that clues only made sense if you removed every C from them—is tied for fourth with Plotkin. Zawistowski, about a minute behind Pasco on every puzzle, falls to seventh with an eight-minute solve. Stan Park is 17th, in pole position for a spot in the C Final, and an outside shot at the B Final. Shannon Rapp is in 76th. Your author has made it back to 67th.

But then, over the course of the evening, the scores are updated. During a judges' review, an official catches that Feyer has an error in, of all puzzles, the relatively easy Puzzle 6: Instead of EATS AT, he’s written GETS AT, and as the crossings are ORE/ORG and TEA/TEE, there's nothing to pique his Spidey-sense that something might be amiss. The penalty drops him all the way down to 10th. Short of a meteorite striking the ballroom, it eliminates him from the possibility of a repeat title. It does set up a spicy proposition: If everyone keeps pace on the Sunday-sized Puzzle 7, the tiebreakers guarantee a new ACPT champion for just the third time in 19 years.

Last of all, there’s the sillier stuff, the kind of tips people relate as potentially apocryphal stories but that many of the top solvers admit they’ve at least considered. For example, the handwriting question always comes up. There’s a belief that precious milliseconds can be saved by writing your letters in a way that minimizes pen strokes: A lowercase “e” is one swooping pen stroke, as is an “E” written like a backwards “3”; an uppercase “I” can save two pen strokes by losing the top and bottom crossings, but then needs to be distinguished from a lowercase “L.” Pete and Claire Rimkus, the pairs team, even told me about how they carefully select the lead in their mechanical pencils, upgrading from 0.7mm to 0.9mm to minimize the chance of breaking a tip, given the writing angles necessary for two people to speed-fill a grid at the same time.

“I tried [changing handwriting] for a bit. I couldn't get into it,” Hinman said. “I don't think making capital E's has cost me any tournaments.” He did allow for one slightly comical admission: “I do have an actual whiteboard that someone made for me once. You know, a 15-by-15 grid with magnetic black squares, much the way the final works. And sometimes I'll print out a really tough puzzle and try to do that final style.”

In the end, relaying all of these tips is kind of like telling you about the practice regimen of Usain Bolt; it’s all well and good to know to keep your posture upright and lift your knees high, but none of us will likely ever understand what it’s like to physically move that fast. But, as Plotkin put it, “if you're just getting into it, don't worry about this stuff. If you already can do a New York Times crossword, if you can finish a New York Times crossword any day, if you can finish a Saturday puzzle on your own, a Sunday puzzle, you're already in probably the 95th percentile, if not higher, of all solvers.”

Puzzle 7 is in the books. Plotkin grabs a minute to break the third-place tie with Hinman, joining Pasco and Nediger on the final stage. Zawistowski finishes in sixth, Feyer in ninth. Park has killed it, booking a spot in the B Final, winning a tiebreaker for the third slot with a one-minute advantage on Puzzle 7. Rapp ends the tournament in 83rd, a jump of 100 placings from the year before. The Rimkuses have routed the pairs competition, with the second-place team closer to eighth than to them in first. Your author finishes in 58th.

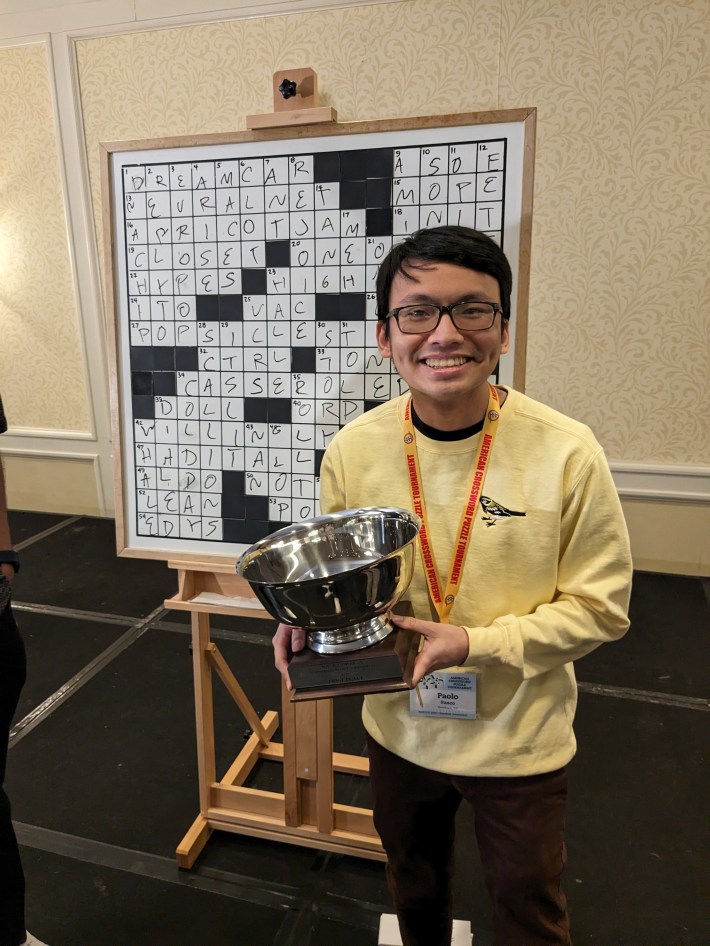

At last, the A Final. Pasco, by dint of his one-minute advantage in the preliminary rounds, starts with a two-second headstart on Nediger, who himself has eight seconds on Plotkin. At first, Pasco dances around the grid looking for gimme clues to get a foothold, plopping in ICE RINK for [Jets and Sharks venue] right away, while both Nediger and Plotkin attack the northeast quadrant first. For a moment, it feels like Nediger is pulling ahead as he completes a full quadrant, but then in a blink of an eye, Pasco nails POPSICLE STICK [Makeshift makeup tool]), one of the central spanners, and then uses that as a base of attack for the northeast quadrant, which he flies through in what feels like a 30-second spurt.

Around four minutes in, all three have essentially completed the top half of the grid, but without much to go on in the lower half, everyone slows down. And then all of a sudden Pasco just goes on an absolute heater, with DOLL [One wearing very little jewelry, perhaps] finally unlocking the southwest quadrant. Seeing Pasco just dart around the board is what I imagine it's like to be in the building for Game 6 Klay Thompson, watching someone go supernova and do something so transcendent that it defies belief. There’s an audible crescendo as the audience—following along on their own copies—watches Pasco fly through the grid while barely consulting the clue sheet that he’s now memorized. As he turns and raises his hand, he has an expression that seems to say, “Did I finally do it?”

Before the tournament, I’d asked Pasco what he’d do if he finally caught the big one. “ACPT weekend, I only drink one beer, I don’t stay up late. [Being at the very top] turns something 100 percent fun into something 90 percent fun, where in the back of my mind, I have to worry about being ready for the game,” he said. “[If I win], I would take one tournament just to hang out. That would be a gift to myself.”

And now that his scratcher has finally paid off, now that the trophy is finally his, does he have any desire to get back on that treadmill on Monday? “No, I really think I’m gonna take a year to hang," Pasco said. "I had a really boring Saturday this year.”