A new league in a country eyed with suspicion by the United States. A singular, shadowy tycoon bankrolling it with the full force of a fortune that might have been at least somewhat ill-gotten, and willing to offer the sun, moon, and stars. Athletes tempted with more money they believed was possible to earn at their chosen sport.

The LIV golf tour? Sure, but more than 75 years earlier, Jorge Pasquel, a Mexican millionaire in what was euphemistically termed the import-export business, attempted to build a league that was the equal of Major League Baseball, and was willing to put his personal fortune at stake to bring the most talented baseball players—regardless of skin color—south of the border.

While that incarnation of the league collapsed under its own weight, its influence did not. From MLB’s integration to the birth of free agency a generation later, the legacy of the Mexican League long outlived Pasquel’s ambition.

Once upon a time, there was an idea of a noble, benevolent person called a sportsman. He owned a local sports team out of civic interest or love of the game, and was indifferent to the idea of his team turning a profit. (This idea never quite matched reality, but it was at least slightly more plausible in the days when margins were razor-thin and a team’s expenses were sometimes covered by its owners at a lunch meeting downtown.)

Some, like Clark Griffith of the Senators, Charles Comiskey of the White Sox, and Connie Mack of the Athletics, came from the playing ranks themselves. Others came from decidedly well-heeled backgrounds, but not necessarily at the scale of the centimillionaires or even billionaires who comprise sports ownership today; up until relatively recently, one didn’t need incomprehensible wealth to own a sports team. And that was due largely to the structure of professional sports, which artificially depressed the going rate for players.

In baseball, it was called the reserve clause. In the early days of the National League, teams were allowed to “reserve” certain players to a team. In 1887, that was broadly formalized into a clause that said even if a player wasn’t under contract to a team, their rights were still reserved by that team. (Whenever some old fart feels the urge to bring up how much better baseball was in the days when players didn’t change teams every few years, feel free to point out that was because those players had no choice.) When the American League formed in 1901, it adopted the reserve clause as well.

If you stayed awake in U.S. history in high school, you have some recollection that in the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt brought the hammer down on a lot of monopolistic practices, wielding the Sherman Antitrust Act as his famed big stick. But when a case challenging the major leagues' monopoly came before federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, he squatted on it until the rival Federal League folded. In what may or may not be a strange coincidence, Landis later became MLB's first commissioner.

The Federal League had been founded in 1913 as a minor league, then declared itself a major league the following year. (The Federal League’s largest physical monument can be found in Chicago, where Weeghman Park, originally built for the league’s Chicago Whales, is now home to the Cubs as Wrigley Field.) It lasted for just two years, but its effects rippled much longer. Players jumped to the new league with the promise of higher salaries, and other players were induced to stay in their current homes by counteroffers. (Tris Speaker fell into the second category. After the Federal League went the way of all flesh, the Red Sox cut his salary back to its previous level. He was irate—so they dealt him to Cleveland.)

The lesson was clear: In the era of the reserve clause, the only thing that could drive up salaries was a competing league, and that was what Jorge Pasquel was determined to provide.

In the words of Life Magazine, Pasquel was “a sinister, swarthy and unscrupulous man of limitless means whose widespread agents operate on a Fu Manchu–like scale.” He was tall, trim, and handsome, dating a bevy of models, and once made a serious run at Ava Gardner. He was committed to physical fitness, spurning alcohol for orange juice and banning smoking in his presence, definitely not the norm in the 1940s. He carried a pistol—pearl-handled, of course—in the waistband of his impeccably cut suits, and once killed a man in a duel. He was described as “the George Steinbrenner of Mexico” by Monte Irvin, the baseball hall-of-famer who knew both men.

“I remember going to his chateau in Mexico City to get paid," Irvin recalled years later. "He had this huge home with fifteen-foot walls around it, and these three enormous Great Danes with him. He also had homes in Laredo, Los Angeles, New York, Paris and Africa, where he hunted big game. On his desk were machine guns. At one point he tossed a .45 caliber handgun to me, just to show it off. I’d never held a gun before! I made other arrangements to get paid in the future. Those Great Danes were big.”

Jorge Pasquel was born in Veracruz, Mexico in 1907, the second of eight children to one of the region’s most venerable families. A year later, Jorge’s father Francisco formed an import-export business. One of Jorge’s earliest memories was hiding in the building that housed his family’s home as well as the business’s wares, while the city was shelled by U.S. warships in 1914. American relations with Mexico were at a particularly fraught point. The Mexican Revolution had ended the year before, and Woodrow Wilson declined to support the government that resulted. It was a time of U.S. occupations and the raids of Pancho Villa. Germany tried to leverage ill will between the two countries by proposing an alliance with Mexico should the United States enter World War I. The interception and leak of that proposal, known as the Zimmermann Telegram, was one of the factors leading to U.S. involvement in the war.

Pasquel completed high school and entered the family business. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1929, described as an anti-Communist who believed in “intelligent socialism.” As a business owner, he was willing to buy labor peace rather than fight. After a brief foray in the military, he took over the family business in 1930—a coup, given that he wasn’t the first-born son—and turned a modest family fortune into millions. (He was also no doubt aided by his boyhood friend, Miguel Alemán, who served multiple roles in the Mexican government before ascending to the presidency in 1946.)

The family’s interests were varied, including mining, retail, industry, and real estate. Because Pasquel did business in and with Nazi Germany after the United States entered World War II (Alemán had earlier arranged a diplomatic passport for him), he was briefly banned from entering the U.S., under suspicion of being a spy. Intercession by Alemán fixed that.

Pasquel had played baseball in his youth, and retained a passion for the sport. In the early 20th century, baseball wasn’t just America's national pastime; it was becoming an international pastime. Central America and the Caribbean became balmy havens for winter ball, and Mexico, with its high altitude and varied climate, became a place for summer ball. Dozens of amateur teams sprung up across cities in Mexico in the 1920s, and the professional Mexican League launched in 1925, with five teams, mostly in and around Mexico City. Never one to watch from the sidelines, Pasquel formed his own team in 1940, the Azules (Blues) de Veracruz, and sought league membership.

The Mexican League’s president, no doubt seeing peso signs, let the team in. The other owners had not been consulted, and some, fearing they couldn’t compete with Pasquel’s fortune, formed their own short-lived schismatic league. Pasquel beat the bushes for new teams, even funding some himself. (He would become league president in 1946.) Suddenly there were two competing Mexican leagues. In need of an influx of talent, Pasquel looked north, to the Negro Leagues, where some of the best players on earth toiled under lousy conditions with no hope of making major-league rosters.

He promised more money. But more than that, he promised a better life than the ones players would be leaving behind. And years later, those players continued to hold him in high regard.

“Jorge treated us like human beings,” said Irvin, who won a Triple Crown in the only season he played in the Mexican League, in 1942.

“I have never been treated better or lived among more hospitable surroundings anywhere,” said former Homestead Grays pitcher Specs Roberts.

“I am not faced with the racial problem,” Willie Wells said at the time. “We live in the best hotels, we eat in the best restaurants. We don’t enjoy such privileges in the U.S. I didn’t quit Newark and join some other team in the United States. I quit and left the country. I’ve found freedom and democracy here, something I never found in the United States. Here, in Mexico, I am a man.”

Pasquel was fiercely loyal to his players. During World War II, he was able to impress upon the U.S. State Department not to draft Fireball Smith or Quincy Trouppe, two Negro League stars who had proven vital talents in his Mexican League. He had the juice to do it, too, offering in exchange scores of workers for the war effort.

In 1943, Pasquel started hiring American umpires—many of whom were available with the minor leagues suspending operation due to the war. Finally, in 1946, he decided to take the next step, opening up his checkbook to MLB players. Pasquel approached the stars of the day, with offers ranging from the six figures to a blank check: Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Hank Greenberg, Bob Feller. (Feller sent a letter declining, prompting Pasquel to call him a gentleman for at least offering the courtesy of a reply.)

All told, about 22 MLB players signed up, though some not for long: Vern Stephens saw the conditions of the Mexican League facilities and quickly returned to the St. Louis Browns. But the players who did make the commitment seemed content with their decisions.

“I assure you, I’m just as happy as [Giants Manager Mel] Ott, and probably less confused,” said outfielder Danny Gardella, who doubled his salary offer from New York.

"I will make as much the first year, including my bonus, as I would in five years at my present rate with the Giants," said Sal Maglie.

“I have no regrets,” Alex Carrasquel said. “Who would—leaving the White Sox?”

Soon after Pasquel began recruiting major-leaguers, baseball commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler announced a five-year MLB ban for any ballplayers who remained in the Mexican League beyond April 1, 1946. Undaunted, Pasquel offered Chandler $50,000 for a five-year term as commissioner of his league.

“How can Chandler banish a free people?” Pasquel asked, perhaps somewhat rhetorically. “The United States is a free country, no? You cannot force to work for you those who do not want.” But dating back decades, the major leagues' owners absolutely could do just that, and did. They also worried about how much longer they’d be able to. The Mexican League—along with a nascent attempt at a labor union, the American Baseball Guild, formed by a Boston lawyer and NLRB administrator named Robert Murphy—threw enough of a scare into baseball owners that they took immediate action.

They formed a committee.

OK, that’s not fair. The committee also issued a report, named for Yankees owner and president Larry MacPhail, that decried the current state of baseball management and implemented for the first time a league-minimum salary. It also declared that a player’s salary couldn’t be cut by more than 25 percent on an annual basis. A pension plan was established, and ballplayers received payments to cover spring training expenses (which even today is still referred to as “Murphy money,” for Robert Murphy, whose unionization effort these preemptive concessions effectively killed). It was a step. But only a step.

The MacPhail Report also admitted that the reserve clause probably wouldn’t stand up in court, saying, “In the well-considered opinion of counsel for both major leagues, the present reserve clause could not be enforced in an equity court in a suit for specific performance, nor as the basis for a restraining order to prevent a player from playing elsewhere, or to prevent outsiders from inducing a player to breach his contract.” It would take another couple of decades before Curt Flood would put this to the test.

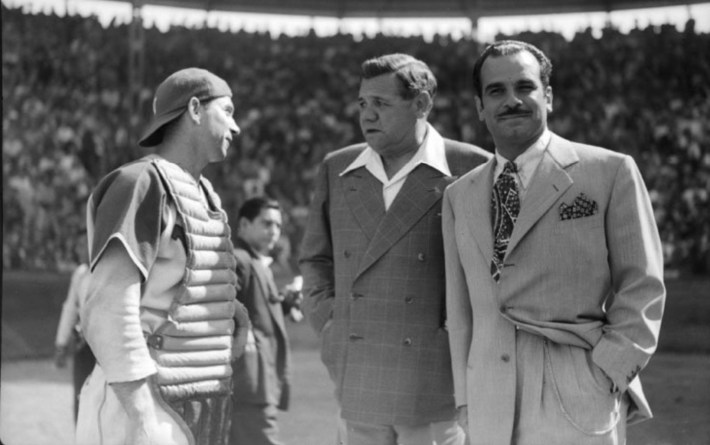

Meanwhile, the Mexican League faced its own problems. American equipment manufacturers, wary of being banned from contracts with MLB, were reluctant to sell south of the border. Teams sought injunctions to keep players from being poached. (In response, the Mexican League countersued in New York, alleging monopolistic practices and claiming the reserve clause held players “in peonage for life.”) Even PR stunts backfired: Babe Ruth, brought to Mexico to wave to fans and sock a few dingers, sparked a fight between two pitchers, after the first had to be replaced with someone more willing to groove up some floaters to the Babe, who was already ill with the cancer that would kill him in two years.

How were the league’s finances? It’s not quite clear. The Pasquels claimed to be breaking even, and the Cleveland Call And Post reported that they were considering expanding with a team in San Antonio, Texas. Collier’s reported a summit with Ted Williams, who in 1946 was making $40,000 in Boston. The Sporting News had reported earlier that year Williams had rejected out of hand an offer claimed to be $500,000, but Collier’s saw a little daylight in the deal. “’You think they'd give me $150,000 down there?’ he asked with a cat-and-canary smile,” the magazine reported. “As if to hint that an offer of that kind had been made by the Pasquels.”

Cardinals owner Sam Breadon (the man who footed the bill when Branch Rickey developed the farm system) held a summit with Pasquel, who'd signed away three Cards players, midway through the '46 season. Instantly, rumors swirled that Breadon was looking to sell—and Pasquel was looking to buy.

Breadon happily put to rest the rumors, but couldn’t deny Pasquel had impressed him. “I couldn’t help but like the fellow,” Breadon said. “He’s one of the most dynamic men I’ve ever met.” (Ultimately, Breadon did retire as owner a year later, after selling the team to Fred Saigh, whose most notable achievement was probably being sentenced to federal prison for income tax evasion while owning the team.)

But it soon became evident that public appetite for Mexican League baseball couldn't match the Pasquels' ambitions or sustain their payrolls. Attendance couldn't grow much, tamped down by facility limits: Most of the league's stadiums couldn’t accommodate more than 10,000 spectators. Pasquel had big ambitions for new stadiums in 1947, but the construction never came to pass. Pasquel began cutting salaries—Max Lanier said his was halved. Chastened, Pasquel announced he would no longer raid MLB teams. (Years later, Danny Gardella would speculate that Pasquel’s real goal in challenging MLB in 1946 was to raise the popularity of his friend Alemán, who was running for president that year. He won.)

Ultimately, the venerable institution and the upstart league negotiated peace, at the behest of the U.S. State Department, which came to view Mexico as a vital ally in the developing Cold War. In 1949, Chandler rescinded the ban on Mexican League ballplayers. At the time of the ban's lifting, three ballplayers were suing MLB for restraint of trade: Fred Martin, Max Lanier, and Danny Gardella. Martin and Lanier dropped their suits and returned to MLB. Gardella, who was not under contract to the Giants but merely “reserved” to them when he went to Mexico, carried on.

“I feel I let the whole world know that the reserve clause was unfair,” Gardella said in 1994. “It had the odor of peonage, even slavery.” Eventually, he settled too—getting one more at-bat in the bigs, with the Cardinals in 1950. Gardella, who died in 2005, said his settlement was $60,000, or six times what he made in his lone season in Mexico.

Pasquel resigned the post of league president following the 1948 season; along with his brothers, who were partners in league and team operations, he fully divested from the league in 1951. The following year, Alemán left the presidency, and Pasquel faded into the background, still wealthy but nowhere near as prominent.

The Mexican League entered an agreement with the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, coming into the fold as a Double-A league. Since then, the league’s been operated quasi-independently, not part of Minor League Baseball’s farm system, but not quite a major league either. Once centered around Mexico City and the Gulf Coast, the league now boasts 18 teams in two divisions across the country—not including the Azules, who folded in 1951.

The league entered its agreement with NAPBL in 1955. On March 7 of that year, Jorge Pasquel flew from Mexico City on an emergency trip to his ranch in San Ricardo. His business at the ranch completed, his Lockheed Ventura took off from an airstrip at the ranch around 9 p.m. It was a clear evening, but only the second night take-off ever attempted at the ranch. The plane brushed the treetops and crashed into a mountain. Pasquel and six others on the plane were killed instantly. He was 47.

Thousands lined the streets for his funeral. A New York Times report from 1983 said that his brothers still wore black ties in mourning 28 years later, and that his office had remained untouched since his death.

The major leagues were integrated by the time Pasquel stepped away from baseball: MLB owners had realized that they could turn a profit off of black players as well as white, as long as they offered better salaries than the competition. Other lasting changes were longer in coming.

“[Pasquel] had a lot to do with the pension plan and a lot of things that came after,” said Bob Feller in a 1979 interview. Feller was the first president of the Major League Baseball Players Association and decried the reserve clause throughout his post-playing career.

The MLBPA remained a loose confederation, devoted more to ensuring a pension for former players (this was the era when two MLB All-Star Games were played annually, with the second one specifically to fund players’ pensions) than any real negotiating for current ones, until it hired United Steelworkers executive Marvin Miller as director in 1966. On Miller’s watch, the union gained strength. Salaries rose, but players were still subject to the reserve clause. Curt Flood sued unsuccessfully to end the reserve clause, but in 1975 a federal arbitrator struck it down altogether. The era of free agency was at hand, and Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League could take at least some of the credit.

“The Mexican League was to prove an immense boon to all ballplayers,” Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times in 1952. “Scared owners granted concessions they never would have granted otherwise and the lot of the athletes in the majors is much happier and more lucrative because of the Pasquels.”