As the year 1946 dawned, a feeling of relief washed over the United States. The largest conflict in recorded history had ended months before. Service members were returning home, factories that were used to build bombers and tanks were returning to their civilian intentions, and people who’d been working on the war effort after the lean years of the Depression were ready to spend money on the consumer goods that would soon be turned out. The United States had been tempered by war, as John F. Kennedy would say in his inaugural address 15 years later, with a hard and bitter peace looming.

In Cleveland, an uneasy peace of another kind was settling in. Two football teams were planning to share the city. One had the imprimatur of the National Football League, even then a beacon of stability compared to other professional football leagues. That team, the Cleveland Rams, had been awash in red ink for the entirety of its existence, even suspending operations for a season during the war. But its fortunes were turning, as its rookie quarterback, a California boy who’d won the MVP award and was married to one of the most famous women in Hollywood, led the Rams not just to their first winning season in the NFL, but their first championship, beating Washington in a corker of a game seen by few due to freezing temperatures and chill winds blowing through the Lake Erie shore.

The other Cleveland team hadn’t even played a game yet, but its owner, smitten with the sport of football after accompanying his son to a Notre Dame game just a few years earlier, was more than willing to spend his not-necessarily-legitimately-earned fortune, starting with the splashy hire of a coach who would revolutionize the game.

The city was easily large enough to support two teams, and details were being worked out for a wary coexistence. There were two main venues that could be shared. League Park was on the east side, with dimensions that seemed odd for baseball (290 feet down the first base line and 380 to left, leading to a staggering 460-foot left field power alley) but turned out to be perfect to accommodate a football field. In fact, it had been the Rams’ home field in their championship season. And at the end of West Third Street, on the Lake Erie shoreline in downtown, was Municipal Stadium. Opened with a prizefight in 1931, it was one of the biggest stadiums ever built, and the NFL Championship Game was held there in anticipation of large crowds that didn’t quite materialize.

That lack of a crowd was but one reason that on Jan. 12, 1946, the Rams ceded Cleveland to the Browns. Owner Dan Reeves had finally prevailed on his fellow owners to allow him to move the team, to the consternation and mockery of many, to Los Angeles. At a time when baseball’s idea of a western swing included trips to Chicago or St. Louis, Los Angeles may as well have been the moon. But like generations before him, Reeves saw gold in the Golden State, telling the Associated Press, “I believe it will become the greatest professional football town in the country.”

Los Angeles was already a bigger city than Cleveland, and untapped, save for a proposed team in the All-America Football Conference, the upstart league that included the Browns. “It was not that I loved Cleveland less,” Reeves told the New York Times, in a nod to Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. “But I loved Los Angeles more.”

The two teams, forever linked in a way that grows increasingly hazy in the league's institutional memory, became powers in the NFL as it rose to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s—and both maintain bonds with their respective cities that were broken but never completely severed. The Rams moved first to Orange County and then spent two decades in St. Louis before returning to Southern California in 2016 (the vote to approve the relocation came on the 70th anniversary of the first move to Los Angeles, coincidentally). The Browns famously left Cleveland for Baltimore, replaced by a new team with the same name in an unprecedented move. This coming weekend, for just the sixth time since the merger, both the Rams and Browns will play in the postseason.

Not only did the Rams’ first relocation to L.A. leave everyone involved satisfied with the results, but it was a transformational one for pro football, for sports, and for American history. Cleveland warmed to its new football team, the Browns, with a love that has sometimes felt unrequited. The Rams became the first major league sports team on the West Coast, paving the way for the rest. And both teams struck a blow for race relations, integrating while Jackie Robinson still toiled in baseball’s minor leagues. Once the dust settled, it was the first time the NFL could truly lay claim to being the national football league.

It’s hard to believe now, but for a significant part of its existence the NFL was on tenuous footing. Initially, pro football wasn’t as well-regarded as the college game, peopled by amateurs who played for the love of the sport. Pro football was considered full of mercenaries, playing for nothing but money. (Of course, it’s probably just coincidence that college football drew from the upper and middle classes, while pro football drew from poor Appalachians and southern and eastern European immigrants who came in droves to the United States—and until 1933, African-Americans.)

The American Professional Football Association was formed at a Hupmobile dealership in Canton in 1920. It was largely a Great Lakes league, with outposts in obvious cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland, but also in such metropolises as Rock Island, Ill., Rochester, N.Y. and Hammond, Ind. It rose from the Ohio League, a semi-pro league that included teams in cities like Akron, Dayton, Columbus, and Canton. For the first decade or so of the NFL (renamed following an owners meeting in Cleveland in 1922), membership was granted to whoever could pay the $100 sponsorship fee. Teams came and went in Duluth, Minn., Pottsville, Pa., and LaRue, Ohio. (That team, the Oorang Indians, was formed as a way for its owner to promote his business breeding and selling Airedale Terriers.)

There was even a team in Los Angeles. At least, theoretically. The Los Angeles Buccaneers were based in Chicago but comprised players from California colleges. When the University of Southern California blocked the use of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum by any pro team, the Buccaneers were road warriors for one season before fading into oblivion. Gradually, the forefathers of the NFL realized that to keep the league afloat, they needed to focus on a smaller league in the country’s biggest cities. (The lone exception? The Packers in Green Bay, which remains the smallest city that’s home to a team in any major league.) The Portsmouth Spartans ended up in Detroit, becoming the Lions. In 1925, the Mara family started a team in New York that, like many other pro football teams of the era, borrowed the name of one of the city’s baseball teams, the Giants.

They were a nice consistent team. They lost a quarter of a million [dollars] and seven games every season.”

Cleveland was a natural spot for a team. The industrial city boomed in the early 20th century, not just the biggest city in Ohio but at one point the fifth biggest city in the country. But it had a difficult time keeping a pro football team afloat. Its charter entry into the APFA was the Tigers. There were also the Bulldogs (a charter member of the APFA, originally in Canton), and teams variously known as the Indians, again, capitalizing off the local baseball team’s name.

In 1936, a new team came to Cleveland, in a new league, the second of four eventual leagues known as the American Football League. The Rams took their name from the successful Fordham University team, with its famed “Seven Blocks of Granite” offensive line, which included a young Vince Lombardi. (It also fit well in headlines, no small consideration in a city that, according to legend, changed the spelling of its name from Cleaveland to Cleveland to fit better on a newspaper page.)

The Rams went 5-2-2, and were set to host a championship game against the Boston Shamrocks, the third meeting between the two teams that year. But the Shamrocks struck because they weren’t getting paid (a check paid to the Rams for gate receipts for the game in Boston had bounced as well), and the season came to an abrupt end. So too, did the Rams’ involvement in the AFL. After the new year, they joined the NFL, where they mostly served as a punching bag for the league’s stronger teams: “They were a nice consistent team,” legendary Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray said. “They lost a quarter of a million and seven games every season.”

But then along came Dan Reeves. Not to be confused with the later player and coach of the same name, Daniel F. Reeves was the scion of a prominent Irish-American family, awash in cash after selling its chain of grocery stores to A&P. Reeves did two things with his newfound fortune. He bought a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, and he bought the Cleveland Rams.

The initial owners of the Rams had been some of Cleveland’s most successful businessmen. They were content to absorb financial losses in the name of civic pride. But Reeves was from New York, and already, rumors were swirling that he’d move the team—to Boston, which found itself without a team since the Redskins (originally the Braves, because baseball) had left for Washington D.C. in 1937. In an effort to allay fans’ fears, Reeves hired Billy Evans, who had served first as an MLB umpire and then as the Indians’ general manager. He had no football experience save for his days playing at the Rayen School in his native Youngstown, but he had more local credibility than did Reeves.

Even then, Reeves was starting to cast an eye westward. He was hardly alone. MLB’s St. Louis Browns, noted for years as being “first in booze, first in shoes, and last in the American League,” were considering a move to Los Angeles. Major league owners were preparing to vote on the measure at a meeting scheduled for Dec. 8, 1941. The day before, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and Los Angeles suddenly became the furthest thing from anyone’s mind—if not an outright security risk. (The 1942 Rose Bowl ended up being played in North Carolina, until this month’s COVID-related relocation the only time it wasn’t played in Pasadena.)

Reeves joined the U.S. Army Air Forces and the Rams suspended operations for the 1943 season. Other teams merged in an effort to ride out the war. California could wait. But yet another pro football league was brewing.

Arch Ward is not enshrined in the pantheon of great American sportswriters. The seminal biography of him is subtitled, “A promoter, not a poet.” Grantland Rice spun flowery verse of Notre Dame’s Four Horsemen and the One Great Scorer. Damon Runyon covered sports and crime with the same breathless storytelling. Dick Young brought a tabloid sensibility to sports coverage. Ward, on the other hand, was an ambassador for sport. He had enough pull, as sports editor of the Chicago Tribune, to bring the first MLB All-Star Game into existence. He also started the college all-star football game, and the Golden Gloves boxing tournament. In the 1940s, after his friend, actor Don Ameche, was thwarted in an effort to buy an NFL team (for Los Angeles, no less), Ward became determined to start another football league. He found a willing participant in another Chicago native, who’d made his fortune in Cleveland.

Arthur “Mickey” McBride’s holdings included Yellow Cab, Cleveland’s only taxi company, real estate throughout Northeast Ohio, and the Continental Press, a wire service that provided horse racing results, making it particularly valuable to bookmakers and racketeers. McBride came to Cleveland as a young man, lured there to work as circulation manager for the Cleveland News. In the days when the newspaper wars actually meant fistfights as competing vendors fought over street corners, McBride hired local guys whose reputations were less than sterling but whose pugilistic skills were without question (some of them later distinguished themselves in organized crime).

A Freedom of Information Act request revealed that McBride himself was on the FBI’s radar in the early 1940s as an organized crime figure—which may have prevented him from being able to buy a baseball team. However, this was not a stumbling block in pro football, where even blue bloods had less than immaculate pasts. It was an era when teams were owned by “sportsmen,” many of whom had gambling interests. Legend has it Art Rooney started the Steelers with $2,500 from a good day at the track, and the Mara family, which still owns the Giants, has roots in bookmaking and New York City’s Tammany Hall political machine.

McBride was uninterested in football until he accompanied his son to a Notre Dame game. Then he was hooked. He attempted to buy the Rams from Reeves, to no avail. He then heard of Ward’s efforts for a new league and wanted in. In 1944, McBride was announced as the new owner of the Cleveland team in the All-America Football Conference.

The home-town feeling never quite developed. In contrast, the All-America Browns will be our team. It’s under home ownership. Its stake is in Cleveland.”

He had little formal schooling, but an innate sense of how the world worked. After being talked out of hiring Frank Leahy away from Notre Dame, McBride went to the Plain Dealer and asked who the best football coach in America was. Without even thinking, sportswriter John Dietrich told him, “Paul Brown.” Brown was an Ohio native, born in Norwalk but raised in Massillon, and had returned to his alma mater as coach after matriculating at Miami University. From there he went to Ohio State, leading the Buckeyes to their first national title, before joining the Navy, where he was coach of the football team at Naval Base Great Lakes in Chicago. McBride put Brown on retainer, promising him more money than any football coach in the country. (McBride knew he was overpaying, but saw the value in the publicity it brought.)

Meanwhile, after returning from hiatus, the Rams had quietly assembled a good team and were actually winning football gaes. The traditional powers in the league—the Giants, Packers and Bears—relied on networks of former players to offer tips and advice on who to sign. The Rams had no such alumni network, so Reeves paid for one, setting up the very first scouting department in the NFL. Evans left after a year as general manager, and in stepped Charles “Chile” Walsh, a Hollywood native who’d played football at Notre Dame and knocked around the pro and college game as a coach. He had a great eye for talent, drafting players like quarterback Bob Waterfield, in 1944, and Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch and Tom Fears, both selected the following year. Walsh also signed so many new players that the Cleveland Press started a regular feature, “Know Your New Rams.”

Waterfield had distinguished himself first at Van Nuys High School, where he met the woman who’d become his first wife, actress Jane Russell, and then at UCLA. As a rookie in 1945 he threw for 1,609 yards and 14 touchdowns—at the time, both fourth all-time in the NFL—as the Rams sailed to a 9-1 record, their first winning record in team history, and the Western Division title. (Waterfield also threw 17 interceptions—but snagged six of his own as a defensive back.)

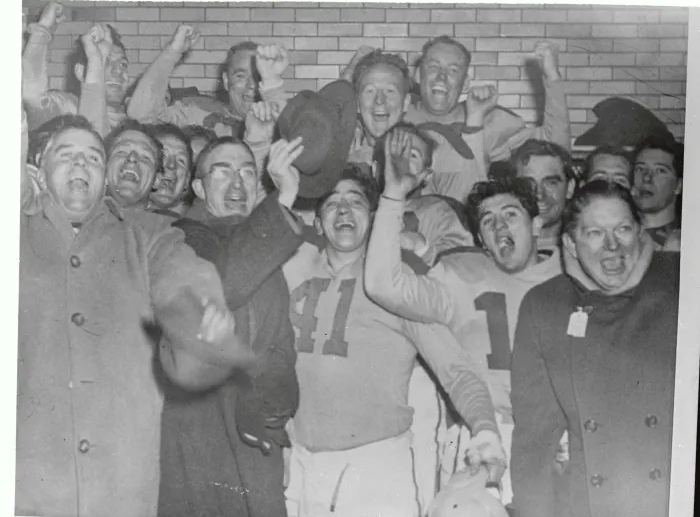

The Rams would host the NFL Championship Game (at the time, hosting duties rotated between the Eastern and Western division champions) against Washington. The announced crowd at Cleveland Stadium was 32,178, big enough that League Park wouldn’t comfortably hold them, but smaller than the crowd of 82,000 that had seen Notre Dame and Navy battle to a 6-6 tie there a month earlier. Those who did show were considered to be either insane or inebriated, as temperatures never rose above 6 degrees, with wind blowing off Lake Erie to make it even colder. A famous photo shows team members sitting on the bench under piles of straw, and there were reports of fires started in the stands for warmth. Waterfield threw for two touchdowns and booted an extra point as the Rams beat Washington 15-14.

(The Rams’ other two points came after Washington quarterback Sammy Baugh, passing out of his own end zone, hit the crossbar of the goal post, which was then located on the goal line. The ball landed back in the end zone for what was then a safety. The NFL changed that rule the following year, thanks in large part to the protestations of Washington owner George Preston Marshall. Still on the NFL rulebooks is the updated rule, which states that any pass that strikes the stanchion, crossbar, or uprights is automatically incomplete. Since the goalposts were moved to the back of the end zone in 1974, it’s not a rule that’s expected to come into play very often.)

With the championship, Waterfield, Reeves, and the Rams were the toast of Cleveland. That lasted less than a month, until the team’s move to L.A. was announced. Where an NFL departure’s team from Cleveland would be met half a century later with lawsuits and fan protests, the Rams’ departure just kind of ... was.

“The home-town feeling never quite developed,” the Cleveland Press opined. “In contrast, the All-America Browns will be our team. It’s under home ownership. Its stake is in Cleveland.”

In Cleveland, there’s a concept called “gets us.” It’s the idea that players and coaches who come to Cleveland can reach some deeper level of understanding with the fans. Nick Swisher went to Ohio State. There was an idea that he got us. Freddie Kitchens’s homespun good-ol-boyness was evidence that he got us. LeBron was from here. He got us ... except for those times that he didn’t.

Paul Brown was from around here, and that’s how he built his team. “Brown had coached nine years at Massillon High School, three at Ohio State and one at Great Lakes,” wrote Gordon Cobbledick, legendary sports editor of the Plain Dealer. “He had intimate knowledge of three main groups of football players; those from Massillon and its opponents, those from Ohio State and its opponents and those from Great Lakes and its opponents. From those three groups, which overlapped in places, he built the foundation for the most phenomenally successful team in football history.”

He got Lou Groza and Dante Lavelli from Ohio State. He’d seen Otto Graham close-up when the quarterback played at Northwestern (the Wildcats had handed Ohio State its only loss in Brown’s first season as coach in 1941). And when someone suggested he try to get Doc Blanchard, who’d just won the Heisman Trophy at West Point, he said, “The man I’ve got in mind is better than Blanchard.” It was Marion Motley, who graduated from Canton McKinley—Massillon’s archrival—and played for Brown at Great Lakes.

Motley was African-American, as was Bill Willis, who’d grown up in Columbus and played for Brown at Ohio State. Believing the ranks of pro football were closed to him because of his skin color, Willis asked Brown for a recommendation letter for a college coaching job. Brown invited him to training camp at Bowling Green State University. (If nothing else, he could provide a roommate for Motley in the days when white players and black players may have played together, but couldn’t live together.) Motley and Willis were the only two African-American players in the entire AAFC. Both were both eventually inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The Rams also integrated, if not quite as willingly. One of the great motivations for the move west was the chance to play in the Coliseum. By this time, the pro game was a little more respectable, and USC wasn’t about to put up the fight they had 20 years earlier. But city officials, lobbied by the African-American press (specifically Halley Harding of the Los Angeles Tribune), declared the chance to play at the Coliseum would only be afforded the Rams if the team integrated. So Reeves signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, both hometown heroes who’d played for UCLA. Both had relatively brief careers in the NFL, with Washington later joining the Los Angeles Police Department and Strode going on to an acting career, with credits including Spartacus and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

The Rams played Washington in an exhibition at the Coliseum in 1946. It drew more than twice the crowd as had the NFL championship game the previous December—to be fair, the weather was a little better. The Browns took the field for the first time in Cleveland, against the Miami Seahawks, in front of a crowd of more than 60,000. They had already captured Cleveland’s hearts. The Browns “got us.”

The Rams were doing the same in Los Angeles, something Reeves made sure of. He started a kids’ club to give away tickets to the games and in 1950, announced a deal to televise their games. That year, the team also made its first return to Cleveland—to play the Browns in the NFL Championship Game.

The AAFC existed for just four years, dominated by the Browns, who won every championship, including a 1948 undefeated season. But two leagues warring for players (as soon as the truce was off, the Browns signed five Rams players) had driven up expenses and left both leagues on wobbly financial footing. Ultimately, the Browns became part of the NFL—as did the San Francisco 49ers, providing the NFL another West Coast team. (It’s a lesson Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley later took to heart; he convinced Giants owner Horace Stoneham to move with him to the West Coast, rather than to Minneapolis, where the team’s top minor league affiliate was.)

The Browns were viewed with some skepticism as a champion of an inferior league. But they opened the 1950 season at the defending NFL champion Philadelphia Eagles, and proceeded to dismantle them before a league-record 71,237 fans at Municipal (later John F. Kennedy) Stadium in Philadelphia. The Browns blew through the eastern conference, and the Rams did the same with the west, meeting on the lakefront a day much like the Rams’ championship game five years earlier: frigid and windy. This time, the Rams came up short, with Groza kicking a field goal for a 30-28 Browns win.

The two teams met again in the 1951 championship, the first nationally televised NFL game, this time with the Rams prevailing.

The Browns were one of the dynasties of the postwar NFL, thanks in no small part to Paul Brown’s genius. McBride sold the team in 1953—two years after testifying before the Senate Committee on Organized Crime—for $600,000, at the time the highest price ever paid for an NFL team. He lived a relatively quiet life until his death in 1972, a year after Dan Reeves’s death from cancer.

By the early 1960s, Reeves and the Rams were flush. The Rams had gone Hollywood, with their distinctive horned helmets (designed by Fred Gehrke, who’d played for the 1945 team) and famous fan base (at one point, Bob Hope was part owner). Reeves’s eye for talent included hiring Tex Schramm and future NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, who helped usher the league to its omnipotence in the 1960s and beyond. Reeves, who was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1967, had bought the Rams for $150,000, basically paying off the debt of the previous owners. At the time of his death, his team was worth more than $19 million, an astonishing amount at the time, but almost quaint in today’s league of multibillion-dollar franchises.

“It was Reeves,” Jim Murray wrote, “as much as Red Grange or Papa Bear or Bert Bell or CBS, who turned pro football from a quasi-pass-the-hat hunk of vaudeville-in-cleats and made it a hard-ticket Sunday ritual.”