A sign of a good museum exhibition: walking out feeling like you know an artist as a person. Nicole Eisenman: What Happened, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago until late September, illuminates its subject in just this way. For those already into the wide-ranging work of Eisenman, this is a hefty collection that will leave you feeling full, like a meal at your favorite restaurant. But for those like me, checking it out on the back of a recommendation, the prevailing thought might be something more like, Nicole Eisenman is really cool, and I'd love to have a lengthy conversation with her. Most of that sentiment comes down to how Eisenman depicts people in her work—rarely the same way twice, but always full of wit and empathy—and the almost-tangible human connection emanating from every wall.

Some exhibitions are structured chronologically, while others focus in on one neat trick that makes an individual historically important. What Happened is less obvious. While it does start at her exciting early-'90s embrace of man-hating-lesbian stereotypes and ends in a spot firmly rooted in the early 2020s, and while the actual words on the museum walls feature stiff, textbooky prose that sticks to "this painting shows x, which represents y" formulations, this doesn't obscure the playfulness on display in the intervening room design, which is dictated less by convention and more by feeling. How would I like people to absorb this collection? One section is called Coping. Another is called Heads. In totality, the work captures a will, as opposed to a résumé.

Eisenman's 2015 MacArthur Fellowship citation declared that her works "restore cultural significance to the representation of the human form," and throughout this exhibition, it's a delight to see how she expresses the recurring miniature triumphs and tragedies of the everyday. There's a sort of wry compassion in something like Untitled (Portrait of a Man Wolfie), in which a man confronts a work of art that mirrors his own idiosyncratic look. There's a broad embrace of spontaneous connection in a painting like Another Green World, which stitches together multitudinous life in a small space. Not unlike hanging out with any person for an extended period of time, walking through Eisenman's art guides you through a farrago of emotions; her work can be arch, soft, fierce, depressed, silly, or so much more.

Nothing in What Happened was as instantly striking as Morning Studio, featured a little over halfway through the exhibition. This is one of the most straightforwardly lovely contemporary paintings I've seen. In Eisenman's style that mixes pop art with subtly rendered faces and some very particular object organization, she captures two women in a moment of shared intimacy on a bed barely big enough to contain them. The woman on top seems most nervous, frail, and in need of connection, as she regards the space occupied by the viewer. It's the woman embracing her, however, who is exposed in a literal sense, yet seemingly entirely unguarded.

With a computer wallpaper of a galaxy projected behind them, the little apartment takes on a mythic scale. Yet there's a down-to-earth romance to this scene, so exquisitely rendered, that any viewer—particularly queer women—should fill up with warmth at the sight of it. This is attractive art that delivers legible beauty, offering a closeness I think we all desire. While the nudity, I suppose, keeps it from being a merchandised standard, Morning Studio is evidence that Eisenman knows what pleases viewers, and understands how to reach a crowd.

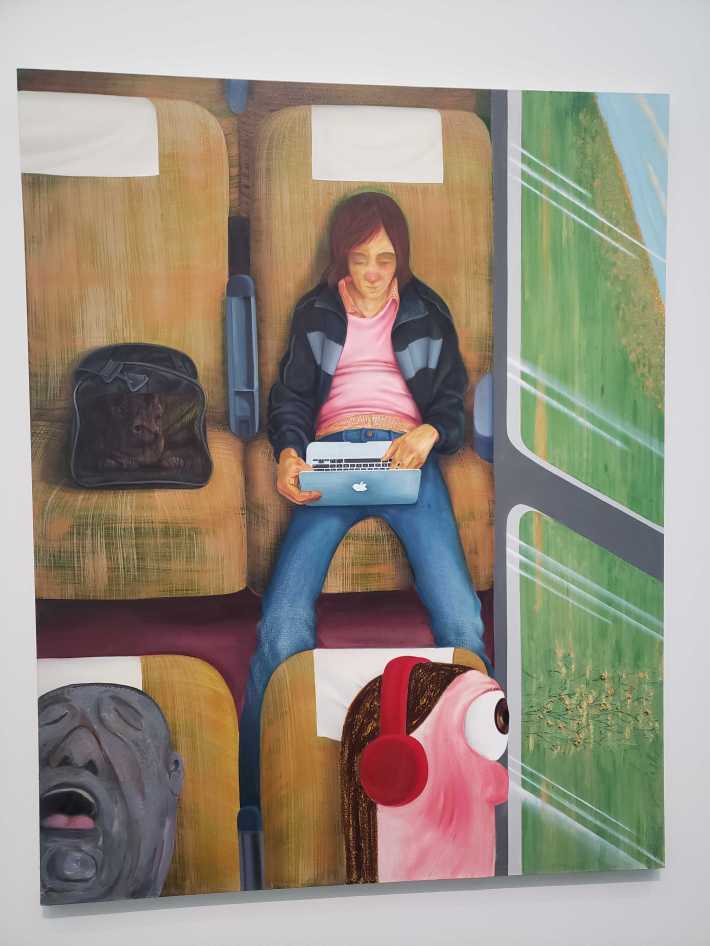

Shortly following Morning Studio in the exhibition, there's another painting that seems to present an entirely unrelated scene. But I keep considering a connection between the two. Weeks on the Train, painted the year before, places the writer Laurie Weeks in a space far less private. Weeks is contrasted by three other lifeforms—one sleeping, one looking out the window with cartoonish intensity, and another chilling in a cat carrier. Those surroundings bring Weeks into focus—tired, overworked, perhaps bored or stressed.

It's a feeling we all relate to, and yet it's one too rarely portrayed in traditional portraiture. I find it to be even more intimate than Morning Studio. That there is enough trust in this friendship that Eisenman could paint Weeks in a state like this—no conquering goddess or stunning siren but simply wiped out and isolated—is invigorating. It's an affirming thing to be able to look at someone in an unremarkable moment and see the art in it. That's the commonality across Eisenman's works, no matter the style or the chronology: They're just people. They're us.