Picture in your mind what hockey looked like at the turn of the 20th century. What, where, and who do you see? Set your mental image in Canada, if you haven't already, as the game had yet to spread much below the border. You probably imagine a less formal affair, games played on ponds and small rinks and not in packed arenas. The sticks are wooden, the players padless and without helmets; the sport itself is slower and more methodical, and any contact is incidental. And when you picture organized hockey's earliest players, they’re probably white.

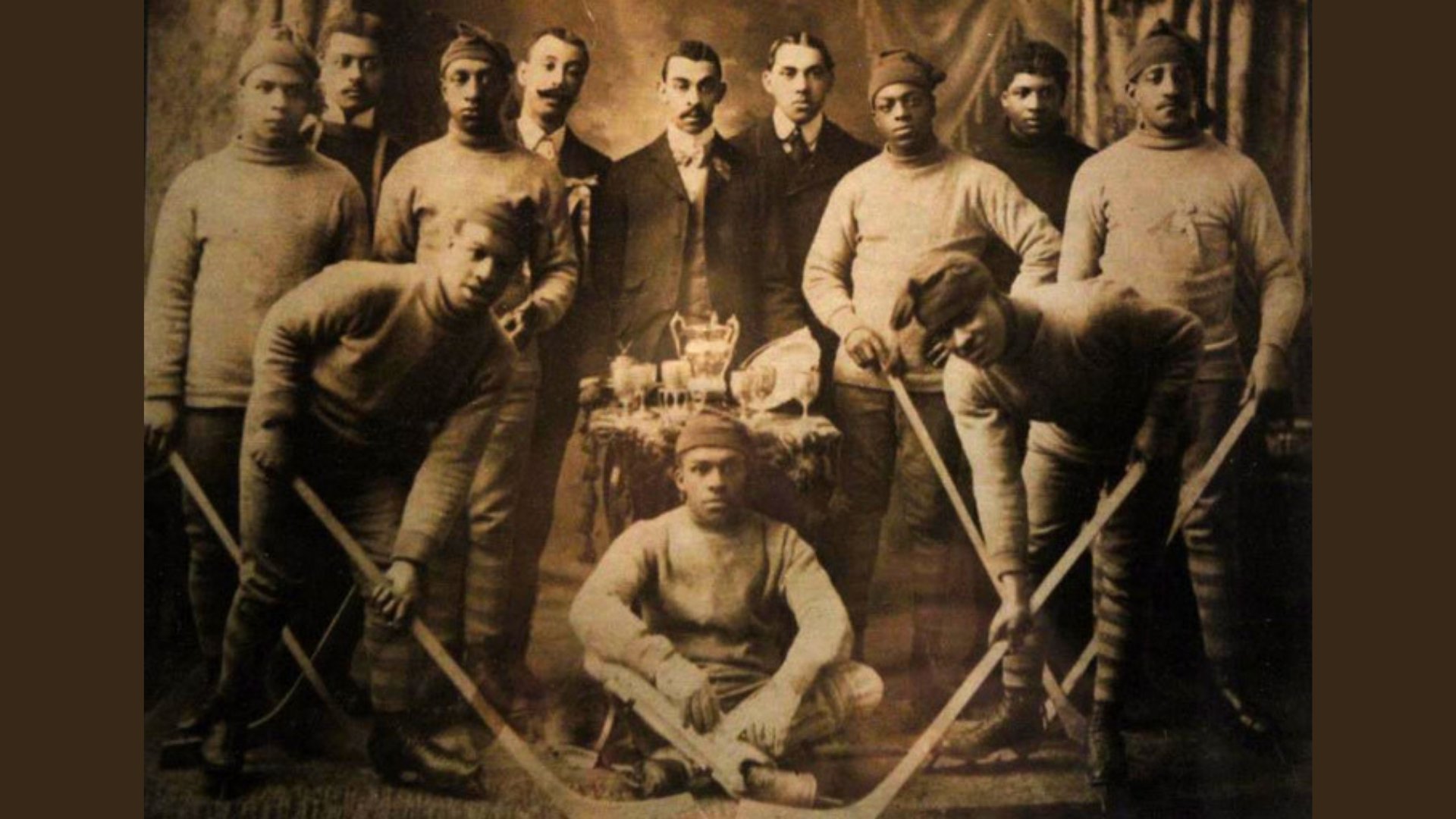

A group of Black Canadian intellectuals and churchmen of the time looked at the sport, and saw the same thing, and decided that simply because things were the way they were, that wasn’t how they had to be. So they started their own league, the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes, which existed just long enough to invent much of what's best about the modern game—before it was killed off by white business interests. As a result of its short lifespan, the CHL doesn't get a prominent place in most tellings of hockey's story, but its legacy is undeniable.

The Canada of the late 19th century had a much smaller black population than it does now (21,400 as of the 1881 census; nearly 2.2 million in 2016), after which the loosening of immigration restrictions in the 1960s paved the way for many more Caribbeans and Africans to call Canada home. Before that, the bulk of the black population in Canada came from the United States. Many were formerly enslaved persons who found refuge in British Canada, which had outlawed slavery decades before the United States.

But just because Canadian authorities welcomed those who had escaped bondage did not mean they viewed them as equals. It wasn’t out of altruism that British authorities in Canada first began offering sanctuary. There was a certain level of opportunism behind the invitation: a desire both to attract cheap labor and to harm America’s economy. Sometimes these refugees were given land grants, but not in the fertile plains of Saskatchewan nor the industrial heartland in Ontario. Instead, they were essentially pushed to the periphery of the Dominion, often forced to settle in the less productive Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. Halifax, the largest city in the region, became a population and cultural center for Black Canadians.

The Maritimes, while not offering particularly good farmland, proved to be fertile ground for a burgeoning intelligentsia, a group of people who sought equality for black people, not just in Canada, but in the whole of the British empire. Their goals went beyond legal equity, instead seeking a more tangible social respect from their new countrymen. Hockey was seen by these organizers as a way to prove and thus obtain black equality. After all, then as much as now, the idea of hockey as a white man’s sport was pervasive. So, in 1895, they formed the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes, the world’s first all-black ice hockey league.

The most famous of these founders was a Trinidadian teacher named Henry Sylvester Williams. He’d come to Halifax to study law and quickly became active in local politics. His advocacy eventually had him run out of Canada by the white establishment. Later in his life he would move to England where he became one of the first persons of African descent to hold elected office, as well as organizing the first Pan-African Conference. The other founders were businessman James A. R. Kinney, pastor James Borden, and attorney James Jonston.

They shared several values, among them an admiration for American civil rights leader Booker T. Washington. It was Washington’s belief that segregation afforded those of African descent an opportunity to prove black excellence, and this philosophy was a major influence on the creation of the CHL. What better way to speak to Canadians in a language they understood than on the ice?

All the founders were Baptists, and their faith influenced the way they structured the league. Each team was to be affiliated with a different congregation, which reveals another purpose of the league: to get young men to come to church.

A common saying among historians is that the CHL had “no rules except for the Bible.” It’s difficult to pin down exactly what that meant, although in practical terms it meant that penalties weren’t often called and goaltenders were allowed to drop to their knees, an illegal move in other leagues. One might assume that a heavily Christian sports league, deeply intertwined with community churches, would be sterile and cautious, but accounts show just the opposite.

One, from the Acadian Recorder, describes play during a fierce rivalry matchup between the Halifax Eurekas and the Dartmouth Jubilees:

“The players were bunched most of the time and did not seem to worry much as to whether it was the [puck] or an opponent’s shins that was struck… Players knocked down were left to get out of a melee as best they could.”

Play was frenetic, with an emphasis on counterattack. Skaters had no bones about slamming into each other, which would have looked strange to hockey fans back then. To that point, hockey had been a slow and calculated game, one that prioritized keeping possession of the puck. The CHL, on the other hand, embraced hockey’s potential as a contact sport.

Partially and at least at first, this may have been because many of the players simply weren’t very good at hockey. Some were experienced skaters, and many of them elite athletes: Jack T. Mills, captain of the West End Rangers, once held a speedskating record of 18 miles in 50 minutes. But by and large, they were baseball players who viewed hockey as a way to stay employed and in-shape over the winter. While they had played informal hockey games before, this was their first taste of professional matches. Many of them quickly developed a love for the game, and it wasn’t long before they began to master it. Charter member teams of the CHL played numerous exhibitions against established white teams, and occasionally the CHL teams would win. The typical response from the all-white teams was a vow never to play them again.

Contemporary sources on the league are surprisingly easy to find. Historians George and Darril Fosty have pored over local newspapers and strung together entire seasons’ worth of scores and statistics. We can gain a fairly comprehensive picture of the league from these sources, and the evidence leads to a perhaps surprising conclusion: The CHL helped invent hockey as we know it.

It was a fertile setup for innovation. Sports thrive in environments where there is no “right way” to play the game. With fewer rules than the established leagues of the time, and operating outside of any tradition for how hockey was supposed to look, the CHL was a place players could experiment. Eddie Martin of the Halifax Eurekas was the first hockey player to ever perform a slapshot, probably repurposing his baseball swing for the ice. His teammate George Tolliver invented the flying body check, according to the Acadian Recorder, and was still playing for the team into his 40s. A third Eureka, Henry Franklyn, may have been the first person to play the goalkeeper position as we know it today, not remaining on his skates but instead squatting and lunging. He was three feet and six inches tall.

Most of the CHL’s teams came from Halifax or nearby towns like Africville or New Glasgow. They tended to play a short year, as they were unable to get ice time until after the white teams had finished their season; this often resulted in something more like a tournament than a true league schedule. More than 12 teams played in the league at various points, but it isn’t always clear from the records which teams participated in any particular season. However, what we do know is that nine out of the first 12 championships were won by the powerhouse Eurekas.

The book Black Ice by the Fostys reveals the personal histories of some of the men who played in CHL. At least eight former players volunteered for the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black unit in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I. Several claimed “Marooner” ancestry, after a group of Jamaican rebels who were exiled to Canada. And while the Halifax Diamonds, forever in the Eurekas’ shadow, never won a CHL championship, they were the 1921 Provincial Baseball Coloured Champions.

It’s difficult to understand how fully the league fell out of the public consciousness. Even descendants of CHL players have been surprised to learn how influential their forefathers were in the development of Canada's national sport. Much easier to figure out is why the league went out of business.

Most sports league failures can be attributed to some combination of managerial incompetence, over-expansion, or waning public interest. The CHL had none of these issues. A decade into its existence it was still selling out arenas across Nova Scotia with a popular, unique brand of fast-paced and action-packed hockey. No, what killed the league was politics.

One of the most important locations in Black Canadian history is a place called Africville. On the outskirts of Halifax, it was home to generations of working-class Black Canadians who found themselves priced out of, and unwelcome in, the city they’d helped build. In 1905, the city of Halifax decided that it needed a new railroad. Local business leaders and politicians were enthusiastic for the project and hailed it as an opportunity for progress and prosperity in their city. And they wanted to lay tracks right down the middle of Africville.

By this time, league co-founder James Kinney was more or less acting as commissioner of the CHL. He had also amassed some political power, which he used to successfully fight against an attempt at segregating schools in Halifax. He threw his entire weight behind stopping the railroad. He demanded that the people of Africville had the right to their land, to their homes, to a say on what went on in their patch of the world.

But Kinney couldn’t stop a moving train. The denizens of Africville couldn’t prove their rights to their land in court, with the land grants in many cases going back more than a century and no paperwork to back it up. The houses came down, the tracks were laid, and before the wounds could even heal, a belching steam engine chugged through the middle of the town as a reminder that progress doesn’t benefit everyone.

In response to Kinney and other local black leaders’ attempts to derail their passion project, Nova Scotian businessmen went scorched earth on the CHL. They refused to have anything more to do with the league, refusing to allow any mention of it in newspapers and banning its teams from renting rinks. The league tried to soldier on, playing games out on rural frozen ponds for a time, but the blacklisting proved a death blow, reducing the CHL to little more than just another rec league, playing matches far away from the once-adoring crowds in the cities that had housed them. It’s not entirely clear when the last CHL game was played, though the last mention of the original incarnation appears just before the outbreak of World War I. There were at least two attempts at reviving the league in the ensuing decades, but neither came close to the original in ingenuity or popularity.

The CHL's founders may have been only partially right when they believed the league could be a showcase for black excellence. They were correct in that it would force white people to pay attention. What they did not foresee was white teams refusing to share the ice with superior black teams, or white business leaders systemically starving the league out of existence when its leaders dared to stick up for their community, or the larger hockey world happily cannibalizing the CHL's innovations then consigning it to the forgotten dustbin of history. Black excellence was largely viewed, it turned out, as a threat. You can decide for yourself if that's changed in the last hundred years.

The injustice done to Africville wouldn’t be the last. In the 1960s, the entire population of the town was forcibly removed and their homes demolished to make way for industrial development: more displacement in the name of progress. In 2010, the city of Halifax issued an apology; to this day, the Africville Museum keeps alive the community’s memory. The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes has no such shrine.