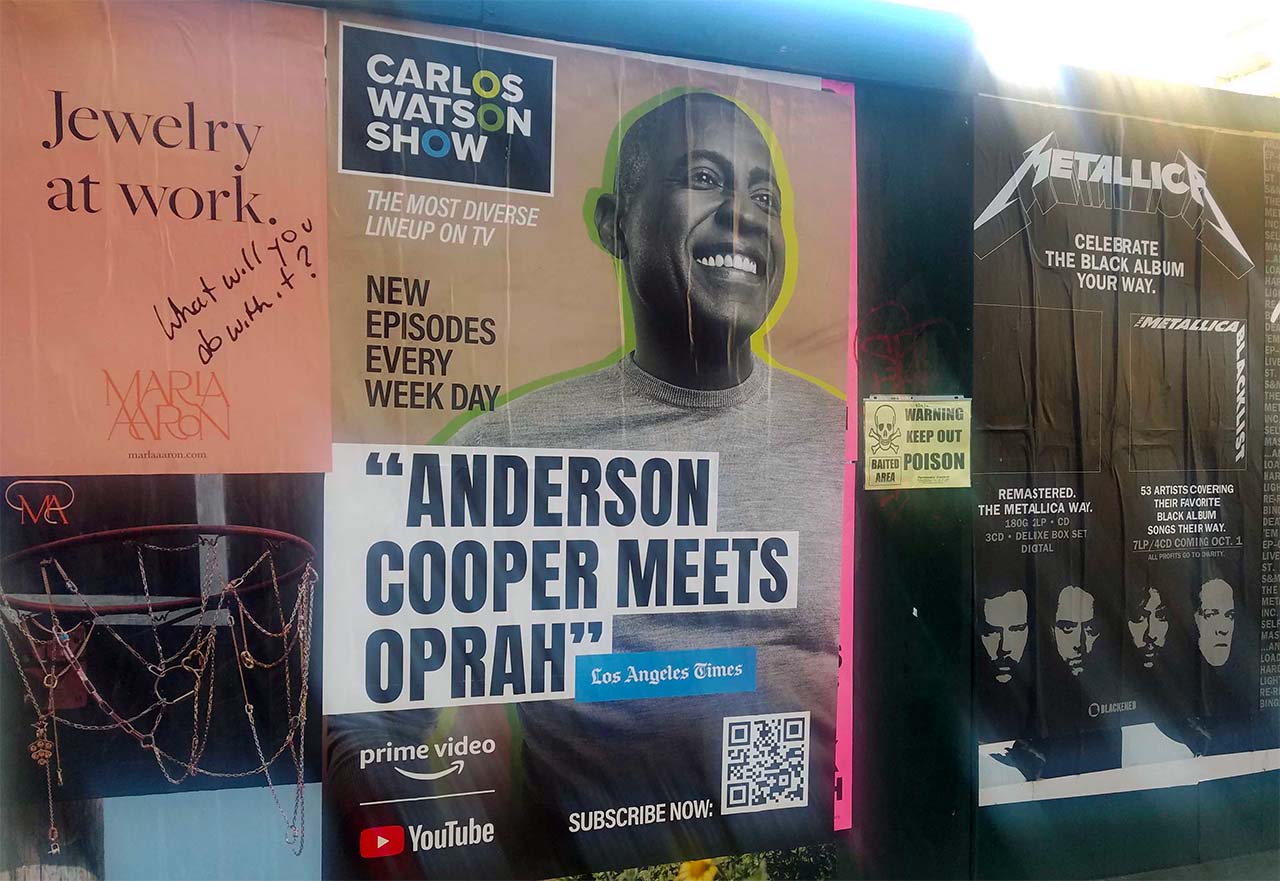

You might have heard of a media company called Ozy. Launched in September 2013 by CEO Carlos Watson and COO Samir Rao, Ozy produced a variety of articles, podcasts, television shows and events. The focus of Ozy, at least officially, was on reporting about “what’s next.” The real outward focus of the company, at least in the last year or so, was mainly about promoting a talk show not just hosted by the CEO but named after him, too. Anyway, none of that is why you might have heard of it.

Though Ozy talked a big traffic game, it was not a popular media outlet. Just last week, a media journalist told The New York Times that he’d “never heard an explanation of Ozy that made sense to me.” An analyst told the paper that its YouTube page “doesn’t really stand out as a breakout channel.”

These are bad quotes to have in The New York Times about your company, but it’s not the reason the key word in the second paragraph is was. Less than a week after a blistering New York Times exposé that included an incident of possible securities fraud, the company announced it would be shutting down on Friday. (This morning, Watson went on Today to announce the company was sticking around, but c’mon. What’s he going to decide tomorrow?)

So what happened? The Times article, by media reporter Ben Smith, hit on the last Sunday night of September. It had a heck of a lede. In February, Rao impersonated a YouTube executive during a call with Goldman Sachs. ("Sure everything is securities fraud," Bloomberg's Matt Levine tweeted, "but this, this is securities fraud.") Rao pretended to be Alex Piper, the head of unscripted programming for YouTube Originals, both over email and on the phone call. Rao's fake Alex Piper praised the company, saying Ozy’s videos on YouTube did great traffic and ad sales. None of those things were then or really ever have been true. The Goldman staffers were suspicious because, Smith wrote, “the man’s voice began to sound strange to the Goldman Sachs team, as though it might have been digitally altered.”

I yelped aloud when I read this story. I sent it to friends and talked about it with my parents. I prodded my wife until she read the whole thing. It’s great. It raised so many questions, and they scrolled through my head as I subjected one person after another in my life to the story. Did Rao use some sort of voice modulator? Why? Also Rao had to be on the call as well, right, since he’s the COO? Did Carlos Watson know? Was he in the same room? Was this the only time they did this? (Watson later said he wasn’t on the call.)

More to the point, this was definitely securities fraud, right? Levine thought so, and wrote a post about it. A lawyer I talked to did, too. (They also agreed that the company's apparent defense for not punishing Rao because he was having "a mental health crisis" at the time was unlikely to hold up in court.) The Times story said that Google dimed Rao out to the FBI. It also noted that, while Goldman Sachs understandably passed on investing, Ozy was able to raise more money later in the year. “The data service PitchBook reports that Ozy had raised more than $83 million by April 2020 and valued itself at $159 million,” Smith writes.

That valuation seems likely to have dropped. Watson called the Times story a “ridiculous hitjob,” which often is what people say when someone writes something mean and true about them. He ridiculed Smith for the long disclosure he included in the story; when Smith was editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed, he met Watson when the companies had acquisition talks. It is funny how Smith’s columns always contain disclosures about potential conflicts of interest. The one for this story notes that he hasn’t yet divested his BuzzFeed stock options! Smith also didn’t mention the two had been on a panel together on a CNBC show this year.

Carlos Watson, Ozy Media CEO, and Ben Smith, New York Times media columnist, discuss regulation of social media and Big Tech platforms after violent posts and bans. https://t.co/vczaTho95I pic.twitter.com/g0aMQ3v4LK

— CNBC (@CNBC) January 15, 2021

This was certainly the most attention that Ozy had ever gotten, but none of it was great. Reporters began to poke around. CNN interviewed nine disgruntled ex-staffers. So did Bloomberg. Insider doubled that, talking to 18 people. I talked to 10 former staffers and freelancers after the week was up. Some of them shared fascinating stories.

One of the first hires at Ozy Media was Eugene S. Robinson. This past winter, Robinson was upset that his job had come to this. Robinson has been in journalism since the 1980s; his title was editor-at-large. He hosted a podcast. He wrote a sex column (“What It Means When Your Wife Says She Slept With George Clooney” was the headline on one entry). He hosted a video series called Eugenious.

In February of this year, some of that work was curtailed. Robinson says Ozy made a shift to focus on newsletters, and so instead of making videos or writing columns he was writing “30-word newsletter blurbs” and cleaning up transcripts of The Carlos Watson Show. His job's sharp pivot from writing and hosting to transcribing the CEO’s talk show came on the heels of a 19 percent salary reduction. (Staffers took pandemic paycuts.) “From February until I was fired in June,” he says, “I was pretty much in a living hell.” He also described the transcription work as “absolute torture.”

Robinson decided that if he was going to be assigned less fulfilling work for Ozy, he wanted to do something on his own. He had started an account on the Substack platform and began using that as a venue for his writing. Eventually, he says, management told him to knock it off. “I said I was told I could do it,” he says. “They responded, ‘You were wrong to do it, and whoever told you that you could do it was wrong.’” Robinson argued with his bosses; he said he was doing this work on his own time, they said that “there’s no such thing as your own time.” He says he was fired in June. Ozy did not respond to detailed requests for comment for this story.

Robinson wrote a long post on Substack about his time at the company, including an incident in which his pay was docked $5,000 (it was later restored) and Rao and Watson making him write letters of apology. “You know I’ve had many bosses over my life but I’ve only had one boss who looked like me, and curiously, this was the worst boss I ever had,” Robinson wrote. “In fact some of the African American employees felt that there were two OZY’s. The white OZY and the Black OZY, where like America, employees were treated worse. The great thing about America though has to do with the mechanics of the melting pot since by the end everyone there was treated like shit.”

Defector granted anonymity to some staffers who had signed non-disclosure agreements upon their separation from the company in order to get severance. One former staffer I talked to, who has since left journalism, still didn’t want to use their name because they feared retaliation from Watson. Another staffer, who had signed an NDA, put it this way: “Carlos is the kind of guy who would be reading articles to try to figure out who said what.” (Things shook out a bit after the company announced it was shutting down.)

All described an uncomfortable, arbitrary, fear-driven culture that shaded at times into overt abuse. Staffers didn’t just have to work for long hours, but were sometimes expected to be at their desks even when there wasn’t work to do—basically, for show. Two staffers told me Watson would yell at you until you cried, and then yell at you for crying. (Rao was more of a “good cop.”) The company often didn’t have a human resources department. Watson talked of Ozy as a family, which in my experience is a trait of bosses who not only have unreasonable expectations of their employees but are also determined to be total weirdos about it. “It was a very strange place," Robinson said of Watson and Rao. "And they’re kind of very strange guys.”

I do not know Carlos Watson. I have only talked to people about him and read things he said and watched him in conversation on video. Here is what I think: Carlos Watson says a lot of things I don’t understand.

“You know, when I met her, she had a severe stutter. Talk about intersectionality,” he told Forbes in June; he was speaking specifically of the poet Amanda Gorman and more broadly, like so broadly that it was unclear what he thought the word might mean, about the importance of intersectionality. If the workplace culture that Watson oversaw was arbitrary, his understanding of the company's broader ambitions was psychedelic. Susie Banikarim used to be editorial director of Gizmodo Media Group. (Here’s my Ben Smith-style disclosure: I was there when she was there; despite being a remote staffer pretty low on the hierarchy, Banikarim knew who I was when I was in the office. Or she pretended to. Either way, I was flattered.) Banikarim recalled Watson saying in a meeting that he wanted Ozy to be the “Uber” for media. Kate Dailey, now editor of Philadelphia magazine, tweeted she got “Starbucks” for media. Did he just mean he wanted his company to be popular?

Another staffer, who asked to be anonymous, told me these kinds of buzzwords were part of Watson's regular vocabulary—phrases that would never quite make sense. “Carlos would digest the Harvard Business Review,” she said, “and diarrhea it out.” Even the name of the company is a reference to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” with an analysis that would get you an F in English class. “The poem is commonly read as a warning against outsized egos and the impermanence of power,” Ozy wrote on its about page. “But we choose to read it differently. To us, it's a call to think big while remaining humble.” (In reality, a former staffer told me: “Honestly, Carlos just thought the name Ozy sounded cool.”)

But everyone at least kind of hates their boss, and lots of bosses say silly things; at the highest levels, saying this sort of executive lorem ipsum nonsense is more or less a media executive's job. Plenty of people reading this have also probably worked long hours in offices, and plenty of people I know who have worked in media have had bad experiences with bad managers. This stuff really is different, though.

Nick Fouriezos worked at Ozy for six years. He said he worked 12-15 hour days managing seven daily newsletters, a feature section, and writing. Then he got shingles. At first, he was told that he would just get one night off. He handed in his resignation two weeks later. He told me it was basically the last straw of a long line of insults from bosses. Eva Rodriguez told CNN’s Kerry Flynn that she worked 18-hour days doing branding for Watson’s show. She had a panic attack. She went to a six-week clinic for depression. One anonymous staffer told me Watson literally threw a book across the room at her. The book was The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers.

It was not just overwork. It was that the work came and went and more broadly existed according to whatever whim Watson was chasing at that time. “It kind of always felt like the editorial team was Sisyphus, trying to push these hugely ambitious projects up a hill,” Fouriezos tells Defector. “And whether they failed or succeeded, the boulder just rolled back down and Carlos had us tackling some other impossible feat.”

While the robustly duffed meeting with Goldman Sachs that led off Ben Smith's New York Times column about Ozy's long, strange hustle did not result in the desired $40 million investment, Watson always had money behind him, including an investment from the German media giant Axel Springer in 2014 and a $35 million round from various private equity concerns in 2019. Laurene Powell Jobs was another early investor, and Watson namedropped her a lot. He told staffers when she liked something they'd done. The relationship between this extremely powerful investor and this objectively obscure property sounds unusually close in retrospect; Jobs came by the office sometimes, and Ozy’s Christmas party was held in conjunction with her company, Emerson Collective.

The overall atmosphere at the site was by all accounts not just intimidating and overbearing, but restrictive. Staffers talked of sponsor interference in stories. But the most important person at the company, the one whose rage everyone feared and whose interests they understood they served above any other, was never in doubt. “It's clear that all roads are intended to lead to the singular subject at hand,” Robinson says. “The guy the TV show is named after—Carlos Watson.” People I talked to described doing fulfilling work, and created stories and video series and many other things they were proud of. Watson did support their efforts many times; Robinson mentioned the work done by Sean Braswell as an example of how this could work well, when it worked.

For many years, that was enough for Robinson to stay. “If you were doing good work that didn't really threaten the Carlos brand, you were allowed to do good work, you know?” he said. “But that really changed in February.” The timing varies from one staffer to the next, but the stories all end the same way. The environment becomes too stifling, the compromises too vast to justify. Robinson left.

In the days after that Times story, the floodgates opened with negative stories about Ozy. Bloomberg’s Gerry Smith and Clara Molot reported that staffers felt pressured to take stock options instead of cash. (Robinson told me that he took the cash.) People continued to poke at Ozy and Watson. At Nieman Lab, Joshua Benton wrote about some of the claims Watson and Ozy made, such as that Ozy would “never tell a story that another national or international publication has already covered”—that claim is on its about page—and that the site offered “a sneak peek of the future,” which Watson himself said on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Benton discovered that Ozy was in fact not the first website to break to the world the prowess of Aaron Judge or Christian McCaffrey or Misty Copeland or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Benton found that one of Ozy's most common claims, that it introduced the world to Daily Show host Trevor Noah, was (in my opinion, at least) more “false” than “exaggerated.” The Daily Beast’s Max Tani chronicled more exaggerations. Slate’s Shannon Palus wrote about the absurdity—and, again in my opinion, the actual offensiveness—of Watson’s "mental health crisis" defense for Rao. A thread of ultra-fatuous smugness and wild serial dishonesty ran through every story about the company.

At Forbes, Jemima McEvoy and David Jeans wrote about the company’s exaggerated claims about Ozy Fest, saying the company was “a dysfunctional organization that seemed to consider fibbing an essential part of the business model. ” Some details: Ozy once claimed it sold 20,000 tickets for a venue that holds only 5,000, and later said that 100,000 people would attend a two-day event that could credibly only fit 15,600 people a day. They even lied about plans to have a petting zoo. July’s event was set to be a big bomb until NYC mayor Bill de Blasio ordered outdoor events canceled due to heat, which allowed Ozy to collect on its insurance policy. Naturally there was a COVID-19 angle, too: Ozy, which had pandemic-related layoffs, got $3.7 million in PPP funding from the federal government for payroll.

Yesterday morning I handed in my resignation to Ozy Media. I was looking forward to working with the talented young reporters but I did not expect this! pic.twitter.com/fc5Ii6ifav

— Katty Kay (@KattyKay_) September 29, 2021

All these stories happened in one week! Katty Kay, a high-profile recent hire who had previously hosted a podcast called When Katty Met Carlos for the BBC World News Service, announced she’d quit by printing out a statement, taking a picture of it with her phone, and posting it to Twitter. Another new hire, Josefina Salomon, quit publicly. Axios’ Sara Fischer and Dan Primack reported that Ozy lost a major investor. Watson stepped down from the NPR board. The Wall Street Journal’s Benjamin Mullin and Suzanne Vranica reported that advertisers suspended $5 million worth of deals. Marc Lasry, Ozy's board chair, stepped down (but remains an investor), citing the need for someone with more experience in crisis management. Watson dropped out of hosting the Documentary Emmys. A&E canceled a co-produced show hosted by Watson that was to air on Tuesday entitled Voices Magnified: Youth Digital Crisis and deleted its webpage. The show was to be about mental health.

In retrospect, it was only a matter of time before Sharon Osbourne got involved. Ozzy Osbourne’s company had sued Ozy in 2017 over the Ozy Fest name, with TMZ reporting that Ozy's defense was that the festival was a “‘media-focused event’—whatever that means.” Watson once said on CNBC that he and the Osbournes were “now friends” and claimed that Sharon and Ozzy had invested in the company. Per the CNBC story by Brian Schwartz, Sharon actually called up CNBC herself this week to say that Watson was lying.

Osbourne told CNBC that Watson brought up Laurene Powell Jobs—“the wife of a guy that died [and ran] Apple,” in Osbourne’s words—and used her money as a threat: “We’ve got her money behind us,” Osbourne said Watson told her. "I’ll fight you all the way." But he also tried a softer approach, she said. "To be honest, he did say, ‘Well we’ll give you shares in the company, but I said ‘your company is worth nothing.’ He said, ‘We have all this backing. All these billionaire people. And you know we can keep on suing you and I can give you some shares.’ But I’m like, ‘Shares in what? What do you do?’” (Watson later said that the Osbournes do indeed have shares in the company.)

There's been a lot of that last question. A common refrain from media members marveling at all of it—the lies that Watson got away with and the money that he raised and the money that the company spent advertising, mostly, him—was that all of this had somehow happened without anyone learning what Ozy really even was. “I have never read an Ozy story," the refrain goes, more or less. "I have never seen an Ozy story, I don’t even know how to pronounce the name of the website. Is it a website from Australia?"

Have you ever consumed a piece of content from Ozy Media?

— Trung Phan 🇨🇦 (@TrungTPhan) September 27, 2021

There is a lesson here for media companies attempting to embark on a sprawling campaign of fundraising and routine workplace browbeating and avant-garde jargon abuse: Make more friends in New York media, so that when you have terrible management decisions, people will at least focus on some of the good work your staffers have done. Ozy did not do this; it launched conspicuously and kept its headquarters in Mountain View, Calif., a place that's home to many more tech companies than media ones.

It seems true that, despite Watson's own relentless claims to the contrary, Ozy did not have a huge audience. But only the claims from the executive suite were actually fake; the stories and videos that the editorial staffers and freelancers produced were real, and in many cases were quite well done. There just never seems to have been any understanding or even good-faith attempt to help that work find an audience. For Watson's purposes, it was much easier to claim that audience already existed, and pay for low-quality traffic when and where the appearance of that audience was needed for business purposes. That appears to have been enough to convince a lot of big media investors to shovel money in his direction.

And it’s depressing! In 2017, Craig Silverman wrote a story for BuzzFeed about how publishers were buying cheap, fraudulent traffic. One of them was Ozy. Robinson told JP Morgan in 2017 that Ozy was hitting its metrics for sponsored content with fake traffic; they only stopped advertising with Ozy recently. It’s incredible how much of the benefit of the doubt Watson gets. The Daily Beast reported that Watson flew to New York in 2017 to convince Inc. to kill a story that would have exposed the Ozy Fest dysfunction. Inc. claims the story was shut down because of a lack of sourcing, which is the kind of thing you say when a powerful person convinced you to kill a negative story. Ben Smith of the Times spent the last seven days or so destroying Watson’s professional life, then wrote this week that, “I am sympathetic to people like Mr. Watson and Ms. [Elizabeth] Holmes—strivers whose dreams apparently led them into deception.” After all of the stories about Watson lying to investors, about staffers feeling abused, about Watson lying about his friendship with Ozzy Osbourne … Smith still considers him a “striver whose dreams apparently let them into deception.” What does a person have to do to be considered a serial liar? How much money does a serial liar need to have before he becomes reclassified as a big-dreaming striver?

It’s especially odd because Watson is continuing to treat current Ozy staffers like shit. On Friday, Ozy announced it would shut down. This morning, he appeared on Today to talk about how he is relaunching the company!

Staffers that were employees as of Friday confirm to @axios that this is the first time they’re hearing of any plans to bring Ozy back. They don’t have access to Ozy email anymore. https://t.co/7JegbgWw7y

— Sara Fischer (@sarafischer) October 4, 2021

“This is our Lazarus moment, if you will, this is our Tylenol moment,” Watson said. “Last week was traumatic, it was difficult, heartbreaking in many ways.” Yes, Watson appeared to be referring to the 1982 Tylenol poisonings when talking about his scammy media company's newest scam. Staffers attempting to hold out for severance or unemployment are now left in the lurch, wondering just what Ozy is going to do next, while their CEO gets to hold forth on TV about how great he is. It may not be happening in the way he wanted, but Watson is finally getting what he wanted. He’s famous! He’s the man on TV talking about how the Tylenol poisonings, first and foremost, were a PR triumph by Johnson & Johnson. He continued doing the rounds on the Comcast networks throughout Monday morning.

"It's heartbreaking. I'm a big fan of Marc's. I've been lucky to get a chance to work with him. He was great as an investor, a board member, a chairman," says @carloswatson on Marc Lasry leaving the Ozy board. "I'm sure he and I both wish last week hadn't happened." pic.twitter.com/XRkDjW7sZj

— Squawk Box (@SquawkCNBC) October 4, 2021

Beyond Watson and Rao and their long, strange grift, what we mostly have here is a real bummer. If you are this many words into this story, I am confident you know the story of the founding of Defector Media. Just like many of the people who left Ozy did on their way out, I went to the head of my old company, told him he needed to treat his employees better, and quit my job. It was one of the best and worst days of my life. Before I did it I registered danspin.org (the .com was taken; I never did anything with it), watched the World Series at an incredible New York dive bar with a friend and a bartender who cheered me up for my impending dive into the abyss, then went to the Times Square McDonald’s at 5:00 a.m. (I wasn’t the only one there crying.) Leaving was both very obviously the right decision and a painful and difficult one to make, but one thing that made the decision to quit much easier was the support that Deadspin staffers received, both privately and publicly. (Some people wrote mean things, too; when I’m in New York, I sometimes consider carrying around a football so I can spike it if I see one of the people who weighed in on that side of things.)

The management screwup at Ozy is very different, though, and the response has been different in turn. When we quit our jobs, a lot of people—even people who didn’t like us—were really supportive. At Ozy, where the work was always a secondary or tertiary concern to everyone but the editors and writers doing it, the people who were treated the worst received no such consideration or support. Not when they were working there, and subject to Watson's rages and hilariously fatuous idea of what a website should be—for all the real journalistic work that got done there, Watson seemed primarily to envision it as a place where people could learn interesting factoids about important celebrities and soon-to-be celebrities a few months before those factoids became more widely known—and not when they left.

“It’s a shame because we invested millions into creating the sham audience,” Fouriezos says. “And we could have spent that money more deliberately building a real one that would have benefited from our reporting. You see it in all the examples of the content, gradually over time becoming more and more Carlos-related.”

The blockbuster success that Watson described to investors never existed, and that somehow never mattered; what the site actually was mattered a great deal more to the people that worked there. It was probably inevitable that the fake stuff would overtake the real. In retrospect, the outlandish volume and scale of Watson's lies about the site seems unsustainable. But, in a strange way, all his dishonesty helped bring his vision into focus. In the absence of any bigger idea or ideal, the endeavor narrowed from a website about Inspiring And Interesting Famous People to one that was primarily about and only served the CEO who desperately wanted to be one himself. In that sense, all that desperate bluster and brazen dishonesty about how popular the site was—it's “growth-hacking” when Uber does it, and just “making up weird shit” when people do—seems primarily to exist to boost Watson himself. On its own, Eugene S. Robinson being told that his job had changed from doing his own work to making sure that his boss's fluffy conversations with famous people were properly transcribed reads like a joke that's a little too on the nose. In context, it fits perfectly.