People hate Jake Paul. He is the walking personification of a Reddit board: a cocky, belligerent white boy who loves to troll as much as he loves to use mental health issues as marketing. His transition from YouTube provocateur to "serious" "boxer" has been built on the calculated decision to fight washed-up black athletes. It’s smart; boxing has always thrived when catering to the public imagination around race war. The desire to see Paul get knocked out by one of the faded avatars of black masculinity he sets himself against explains much of the draw of his fights. His savvy protection of that appeal explains why he only fights people he can comfortably beat with his young legs and just-about-competent skills.

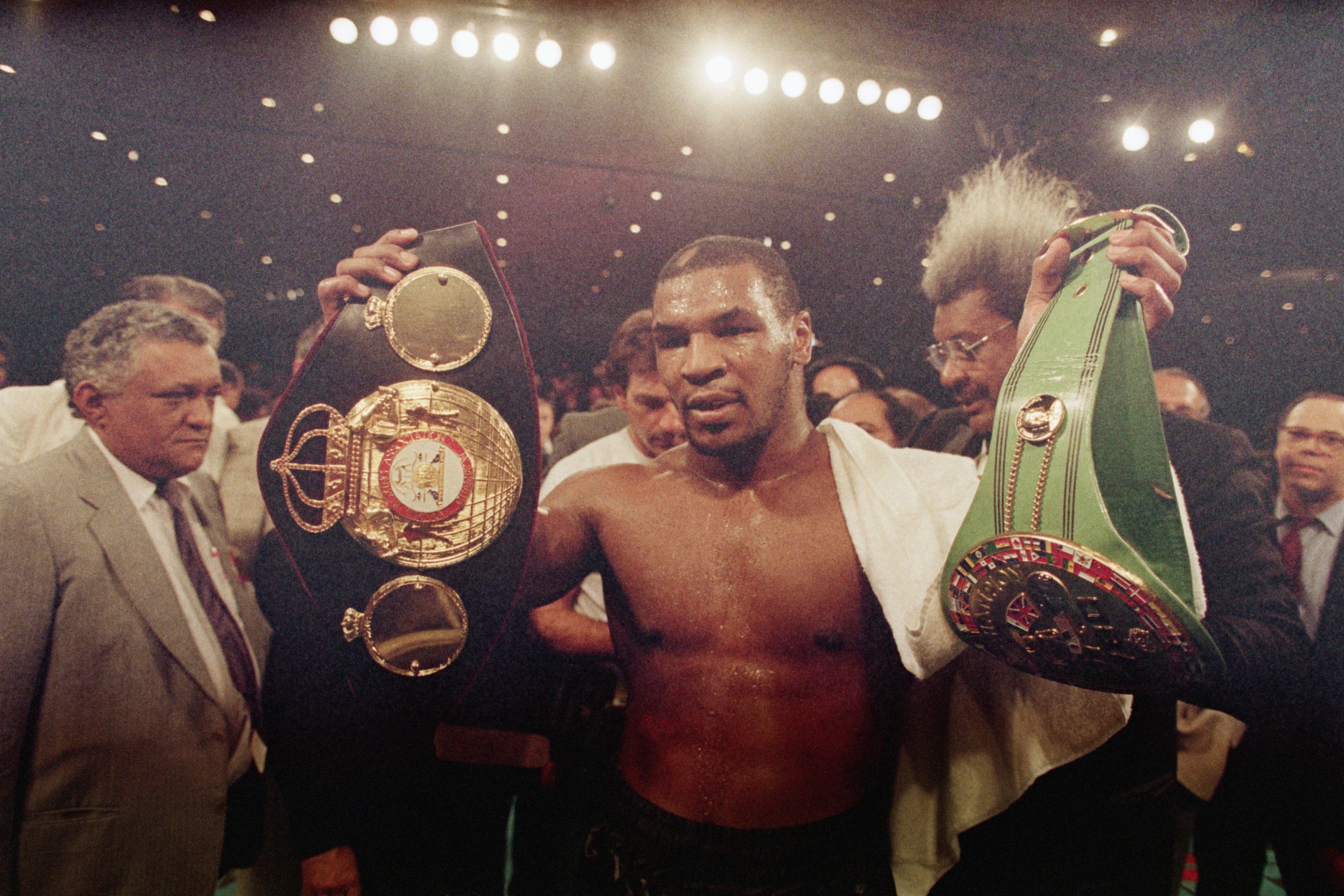

When it was first announced that Paul planned to fight a 58-year-old Mike Tyson, the initial response was one of widespread incredulousness. Over time, people seemed to convince themselves that somehow a geriatric Tyson could be the one to finally put Jake Paul “in his place,” whatever that might mean. It always made sense why Paul would want to fight an old Mike Tyson. But what exactly was in it for Tyson? Money, surely, but that can’t be the only reason. This is a man in his late 50s, who’d been mostly retired since the early 2000s. The people who got suckered into caring about this fight didn't want to see that reality, transposing instead an image of the Mike Tyson of yore, maybe older and slower in some vague way, but still in possession of the exhilarating, terrifying power and violence that made him a legend. On some level, maybe Tyson wanted to see that too.

People love Mike Tyson—even with everything he’s done, both of the self-admitted and credibly accused varieties. It doesn’t hurt that Tyson has spent the last 20 years rehabilitating his image: books, interviews, one-man Vegas shows, self-aware cameos in The Hangover and How I Met Your Mother. By presenting himself as candid, vulnerable, and well-spoken, he went from the scariest, craziest man in the world to America’s reformed, cuddly pet pit bull, like Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, or Ice-T before him—an important step for someone of that archetype to ingratiate themselves into proper A-list celebrity.

But Tyson's transformation never felt fully complete, and especially of late, it's felt like he was regressing. You can hear it in interviews when the past comes up. It's there in the Allen Hughes documentary about Tupac and Afeni Shakur, Dear Mama, in the giddiness in Tyson's voice when talks about the thrill of fighting and being in the ring. You can tell he misses the violence. It's in the following clip from his appearance on Sugar Ray Leonard's podcast, when he talks about both being afraid of and pining for his old self. He’s on the verge of tears just thinking about how much it scares him that he still wishes to be the monster he once was.

And he was a monster, in the ring and out of it. A Category 5 hurricane built to destroy everything in its wake, even himself. The mythos of Tyson is more important than the actual athlete now. It's been almost 40 years since that mythical Tyson actually existed, but the searing image of that version of him is still the memory that people keep holding onto. It's also the image Tyson himself is holding onto, even knowing the toll it took on himself and the world around him.

Which again raises the question: Why would Tyson do this? And why do people want to watch it? As the animating spirit behind American entertainment, we've long passed the point of cynicism and have plunged straight into nihilism, in which pop culture becomes a circus that prioritizes depravity, meanness, and ugly drama as shortcuts to attention and an emotional response. Whether it’s Trump mimicking oral sex on a microphone at a rally, The Rock starring in the latest tax write-off for a streamer, Pat McAfee turning ESPN into his personal frat house, or Ryan Reynolds doing anything, entertainment doesn’t just treat you like you’re stupid and lazy, but like it actively despises you, spits in your face. Netflix's presentation of the Tyson-Paul fight fit right into this landscape: the glitchy transmission and the poor commentary team that featured Mauro Ranallo, Roy Jones Jr., and freakin' Rosie Perez. All of it felt cheap, unprofessional, and completely disrespectful to its audience.

And that’s before you get into the actual match, which was eight rounds of plodding around and occasionally landing a few punches. Even Paul, in all his shamelessness, couldn’t bring himself to knock out or even risk dangerously hurting this withered "fighter." How anyone could convince themselves that a man near 60 and coming off a major health scare made for even a halfway credible boxer is beyond me. At the post-fight press conference, Tyson talked about himself as though he were Rocky, just a shnook who proved he could go the distance.

Before the fight, when Tyson was interviewed by kid reporter Jazlyn “Jazzy” Guerra, he said he didn’t care about his legacy, calling the very idea meaningless before the nullifying finality of death. I believe him when he says the concept of legacy has no hold over him, because no one who cares about that would have done this. This was an ego play. A money play, too, but crucially an ego play. It was a chance to feel like the man he hasn’t been for nearly 40 years. In that context, the whole affair was depressing all around. Depressing for a great ex-athlete to degrade himself to feel the heat of glory once more. Depressing for an audience in the throes of an imaginary nostalgia for an era of fearsomeness that most of them only experienced via echo. Depressing for all the scammers and hustlers who saw in this spectacle a chance to make money off our stupidity. Depressing for the once-proud sport of boxing, which has been reduced to this.

There’s nothing wrong with getting old, despite what you might hear from wealthy megalomaniacs who think they can suck the blood of the young and live forever. As someone raised Christian in the evangelical South, death has always been something I understood as not just inevitable but potentially beautiful, so long as you have done enough to get into heaven and sit by the Lord. It was actually a surprise to me to find out not only that many people never think about or develop a healthy relationship to death, but some, particularly those with a lot of money and a lot more ego, think they can find a way to stave it off.

Death is, of course, scary. It scares me to this day, as I don’t exactly buy into heaven or hell. But it is good to understand that it will come for all of us and that we are but dust in the wind, tears in the rain. Money, science—whatever else can improve your living for some time, but only for some time. I don’t know if Tyson is one of these rich people who think they can beat death, but I think boxing professionally at 58 years old is the action of a man trying to deny the inexorability of the passage of time, trying to prove that he is not close to the grave and that “the real” Mike Tyson—the young, fierce, powerful boxing prodigy—is still there, inside of him.

Maybe he proved that to himself on Friday. I’m not so sure. The only thing I saw was a struggling old man being abused by Jake Paul and Netflix. A gross display of egomania, and our own depraved entertainment culture laughing in our face for actually watching the turd it just took. Maybe Tyson can’t feel his age by boxing, but I certainly did by acting witness to it.