There is a pleasing symmetry to the Mission: Impossible brand cycle: 30 years between the 1966 debut of the original CBS television series created by Bruce Geller to the 1996 cinematic reboot starring Tom Cruise, and again between that first film and what would appear to be the final installment of the franchise this summer with Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning. A childhood favorite of Cruise’s, the original show is, for anyone tempted to look back, a portal to an era of American television that was willing to be goofy. Still, Mission: Impossible was always a heist series at heart. Inspired by the 1964 film Topkapi, which features a team of thieves attempting to steal from the titular palace of Sultan Mahmud I, Mission: Impossible the show melded the heist plot with obligatory espionage elements at a time when James Bond and Get Smart followed similar trends.

By now, almost no one thinks of the television series, so wholly has the film franchise and its zealous lead actor taken over the past three decades, weathering sea change after sea change in the already turbulent, risky landscape of Hollywood. Behind it all, of course, is Cruise himself, who began Mission: Impossible as the first project for the now-defunct Cruise/Wagner Productions.

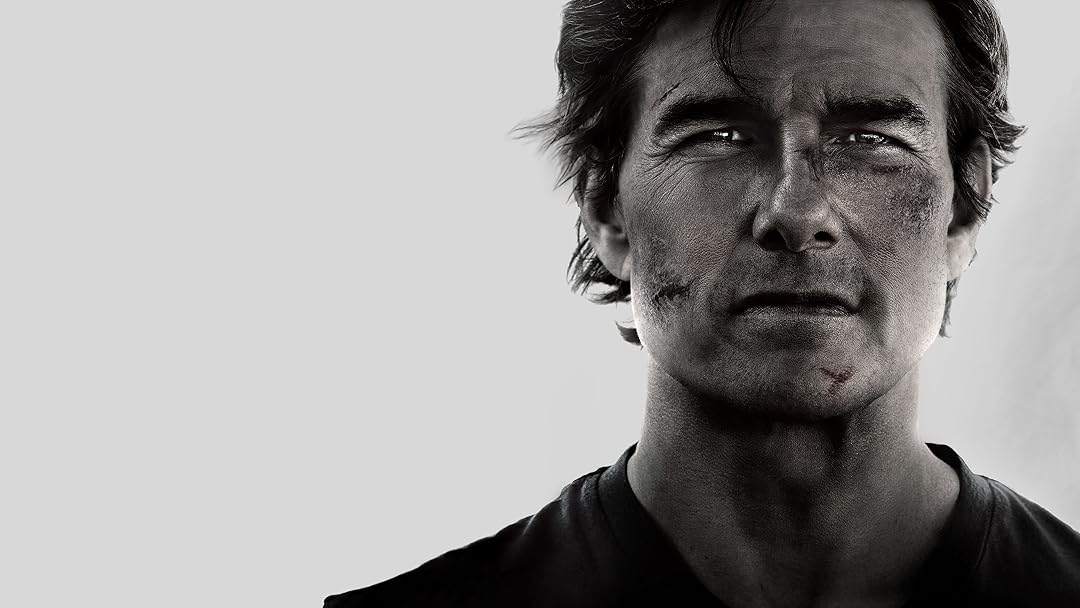

In the last half-century, many major actors created bespoke production companies so they can exert greater creative control over scripts, directors, and budgets. Perhaps what most distinguishes Cruise is his unwavering demand that his name be prominently displayed wherever he goes, as many times as possible. Leonardo DiCaprio has Appian Way, Jake Gyllenhaal has Nine Stories, Brad Pitt has Plan B (which, contrary to what I believed, is not short for “Brad”). Tom Cruise has only ever had his name first and lately, in the wake of Cruise/Wagner’s dissolution in 2008, his name alone. Mission: Impossible –Dead Reckoning Part One’s opening credits immediately illustrate the fixation: “A TOM CRUISE Production” is swiftly followed by “TOM CRUISE.” It’s fitting, since these films have largely been responsible for his transition in American culture from Tom Cruise to TOM CRUISE. Tom Cruise had to wrestle his career from the brink after a series of flubs and scandals during the aughts. TOM CRUISE admonished his film crew during COVID for slacking on health and safety protocols. And TOM CRUISE is credited with almost single-handedly bringing audiences back to theaters.

Mission: Impossible is the essential kernel at the heart of Cruise’s career. It launched him to a new strata of fame, reoriented his perception as both a serious actor and a bankable action star, and, later, saved him from the maws of obscurity and desperation that trap so many aging actors in their twilight years. Now, the end of an era.

A couple of years ago, I wrote that “Ethan Hunt is one of the most transparent acts of public relations management in modern cinema history.” Cruise gets away with a disturbing private life and monomaniacal public image in part because of how well he’s deployed his charisma, physical prowess, and genuine instinct for cinematic story structure in Hunt. As Jon Voight’s character says to Ethan in the first film, “Hide in plain sight, highest possible profile. You game?” to which Hunt responds, “Wouldn’t have it any other way.” Across installments 1 through 4, audiences watched a movie star contort through a series of personas, at once grave and light on his feet depending on how confident Cruise was feeling about his public perception. The Mission: Impossible franchise has always been a petri dish for the ways that Cruise wants to literally be seen. Each sequel photographs Cruise in a distinct way, whether in the slow-motion grandeur of John Woo or the steely, controlled gaze of Brad Bird. Hunt, the ever-capable IMF problem solver who inspires the people chasing him to wax poetic about his near-superhuman ability to do just about anything, is a friendship generator. His loyalty to allies new and old, along with Hunt’s signature in-over-his-head expression of surprise, fear, and determination, endears him, and Cruise, to the world. In order to emphasize this central goodness, Cruise’s control of the script naturally dovetailed with his authority to choose a director who could match his vision. The throughline of the entire Mission: Impossible series has been Tom Cruise doing everything in front of the camera. So too behind it.

With writer-director Christopher McQuarrie, whom Cruise has called his “creative brother” and someone he intends to work with for the rest of his life, the series changed drastically. Not just because McQuarrie bucked the Mission: Impossible trend of changing directors every movie, but because Cruise found a willing long-term collaborator for his entire brand. McQuarrie has contributed officially and unofficially to all but three of Cruise’s films over the last 15 years, each time with increasing creative and editorial involvement. This reflects McQuarrie’s competence, a much sought-after quality for Cruise, as much as the duo’s parity of vision and scope. With smaller projects like Jack Reacher, which McQuarrie wrote and directed, the audience catches a glimpse of a more malleable Cruise persona, battle-hardened but playful. This same sensibility carries over to Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, the fifth installment and the beginning of McQuarrie’s tenure with the franchise.

Mission: Impossible has never been a consistent franchise. Its tone has always shifted, its style reflective of prevailing tastes, whether embracing or pushing against them. Cruise embattles himself, throwing his avatar into dangerous situations so that he might scrape his way out of them bruised, weathered, and recognizably human. In the McQuarrie era, Hunt has been fashioned as an old-school hero surviving via analog methods, uncompromising in his beliefs, hemmed in by bureaucracy, and motivated by an unerring sense of righteousness. In an increasingly artificial, digital world, Hunt is a flesh-and-blood catalyst for human judgment and, ultimately, goodness. The test run for this very posture played out in 2022 with Top Gun: Maverick, where Pete “Maverick” Mitchell serves as the living embodiment of tactile superiority over ephemeral technology. It makes sense, then, that the last two films of the Mission: Impossible franchise, Dead Reckoning Part One and The Final Reckoning, pit Hunt against a nearly omniscient AI called the Entity whose moral code is nonexistent and whose capacity for problem-solving is inhumanly vast.

The problem for Cruise, and Mission: Impossible, is that these last films show the slippage between character and actor far more than usual, the primacy of Cruise’s ego infecting the story and everyone in it. Put another way, the series became a slog. In Dead Reckoning Part One, McQuarrie and Cruise retcon Hunt’s past to include a one-note villain that The Final Reckoning quickly forgets about. It contrives the IMF as a repository for orphans and criminals who might reform their wayward souls by taking something called the Oath. It shows Hunt to be a death magnet for brunettes who look vaguely like Katie Holmes. It forgoes any of the humor, both physical and situational, that endeared Cruise most to his global audiences, the kind of slapstick haplessness that silent film stars and Jackie Chan perfected. Most damning, it takes its legacy and itself way too seriously, turning a kinetic, high-spirited franchise into an interminable bore, replete with overlong expository dialogue, pandering self-referential nostalgia, distractingly obvious CGI, and an obsessive focus on Hunt, at the expense of the supporting cast of characters who help bring out his charismatic wit.

If the Mission: Impossible series is a paradoxical fantasy of Tom Cruise as an all-too-human everyman, who is also singularly capable of bringing order to a chaotic planet, it’s fitting that The Final Reckoning finally crumbles under the weight of that contradiction. Unfortunate, given how much effort has been put into emphasizing—in behind-the-scenes footage, chat show conversations, and Olympics promos—how central these Done For Real stunts are to the franchise that here, Cruise ditches Buster Keaton, whom he gestured to in the third-act train sequence of Dead Reckoning, along with any of the silent icon’s impishness. The presence of the Entity forces characters to speak in totalizing generalizations: everyone, everywhere, anything, no one, nothing, ever. Pages of dialogue are rattled off between characters whose only task is to emphasize the Entity’s awesome destructive power by saying the same thing over and over again: the AI is evil, the world is in danger.

All well and good, but the Entity is an ephemeral presence without any visual dynamism to it. Symbolized as a swirl of blue code in the shape of an eye, the Entity remains simply an image that moves invisibly through the world, hacking nuclear systems and rewriting the internet so that anyone with access to a wifi connection is plunged into a reality without reliable fact or evidence. Hunt faces off against this ghostly enemy via a proxy, the loyal emissary named Gabriel, one of the franchise’s most boring antagonists. Where Dead Reckoning retconned Hunt’s past to include Gabriel as the catalyst for his joining the IMF in the first place, The Final Reckoning dives headfirst into the realm of nostalgia, not only incorporating the fake flashbacks from the previous film which show Gabriel and a smoothed-out Ethan, but key scenes from every installment in the franchise. McQuarrie and Cruise walk down memory lane repeatedly throughout The Final Reckoning, referencing old villains, MacGuffins, and side characters: the rabbit’s foot from Mission: Impossible III, the hapless CIA analyst Ethan steals from in the first film’s iconic tightwire heist sequence, even the knife that Ethan left behind in the vault. The irony here is the audience is reminded of more menacing characters, like Philip Seymour Hoffman’s arms dealer, and more streamlined storylines.

The first hour of The Final Reckoning is edited at breakneck speed, but little of consequence happens, apart from a major character death, which, like the death of Rebecca Ferguson’s MI5 agent Ilsa Faust in Dead Reckoning, feels conspicuously contrived. Hunt’s new band of outcasts, including Hayley Atwell as the pickpocket Grace, Pom Klementieff as former Gabriel lackey Paris, Greg Tarzan Davis as American intelligence agent Degas, are headed by Simon Pegg’s Benji but it rarely feels like they’re a real team of equals. Grace, in particular, represents an awkward addition to the proceedings, her character far more passive and bewildered than Ilsa, who was introduced as something like Hunt’s female doppelganger in Rogue Nation. One senses that with Ilsa, McQuarrie and Cruise crafted a dynamic character who was too willful, too recognizable as an active participant and, per the priorities of the final two films, less believable as the more pliant love interest Cruise is clearly interested in having.

And where the relationships feel thin, the stakes in The Final Reckoning, reiterated ad nauseum, are so massive that the audience becomes numb to their world-annihilating consequences. This narrative portentousness was always embedded in the fabric of the Mission: Impossible franchise but never with such po-faced emphasis and never with this little humor. These used to be action movies about friendship and trust, and thus the tension reached its peak when Hunt’s closest friends were in danger. Of course, Cruise can’t allow for such small but intimate stakes to be the main point of concern. What was once an endearing, even winning element of these films curdles as once distinct personalities become chess pieces to be moved around the board.

Finally, about halfway through, The Final Reckoning remembers that these films live and die by the quality of their elaborate setpieces. A lengthy sequence in the corpse-ridden interior of a sunken submarine offers a welcome respite from the film’s frenetic pacing. Crucially, it underlines why people buy a ticket to these movies: to watch Tom Cruise do something insane. Cutting back on the previous film’s distracting use of CGI and focusing instead on the tension of watching Cruise solve an increasingly dire set of physical problems, The Final Reckoning offers tantalizing glimpses of what the series does best.

Still, it’s plain to see the narrative gears clunking as things drag on. Welcome new faces like Severance’s Tramell Tillman and Ted Lasso’s Hannah Waddingham feel like perfunctory stabs at variety among the cast. The more talk there is about the potential eradication of humanity, the less frightening it becomes. Cruise’s allegory of the fight between analog and digital doesn’t cohere because the true conflict is effectively between Hunt and God. There’s sound and fury to be had in The Final Reckoning, but the film stands as a potent example of the consequences of getting high on your own supply. Cruise, a capable dramatic actor, is intoxicated by his own legacy, which he sees as inimitable. Hence the several masturbatory passages throughout the film where characters thank Hunt for merely existing and, in some cases, seem doggedly grateful for the opportunity to sacrifice their lives for him.

Tom Cruise is a singular force in Hollywood filmmaking who is willing to do what other performers won’t or can’t. The result is one of the best action franchises ever made and, here at the end, one of the most disappointing, helmed by a man who is incapable of separating his fame, power, and pride from his work. Buy a ticket to a Tom Cruise movie and you’re buying admission to one man’s extended fantasy of his own greatness, no matter how ardently he claims to be making them for you, the viewer. The pleasure of Mission: Impossible was always its commitment to tactile craft and motion. The dilemma for audiences, and for posterity, is whether the tradeoff for Cruise’s ego and the slipshod results are worth it.