If you enjoy old-timey American pastimes, have I got a weekend for you! Three consecutive nights of televised title fights! Who invited the mid-1950s?

The fistic windfall kicks off tonight with a poorly planned and bizarrely promoted but intriguing-as-all-getout three-fight, Saudi-sponsored pay-per-view outdoor card at Times Square in New York, with a feature match pitting Ryan Garcia coming back from a PED suspension and intoxicant-addled haze to face Rolly Romero for a welterweight world championship belt. Then on Saturday, boxing's top international draw, Mexico's Canelo Alvarez, celebrates another Cinco de Mayo season in the ring in Riyadh, boxing's new Las Vegas, where he'll fight perhaps the most anonymous champion extant, William Scull, for a super middleweight title. And the capper, maybe best bout of 'em all, comes Sunday in the old Las Vegas, as Japanese KO king Naoya Inoue brings his powers to the west to face Ramon Cardenas for the undisputed junior featherweight championship.

Throw in that all these fights are boxed around the Kentucky Derby, and you'd have newspapers putting several stories about horse racing and boxing above the fold of the sports sections—if only newspapers and sports sections still existed. (Don't forget that the favorite in tomorrow's Run for the Roses is Journalism.) Just get me to the couch on time!

"I can remember many times being in Las Vegas for a fight and the casino being filled with people betting on the Kentucky Derby," Jim Lampley, among a handful of history's most famous fight callers, tells me, "so this is like the old days."

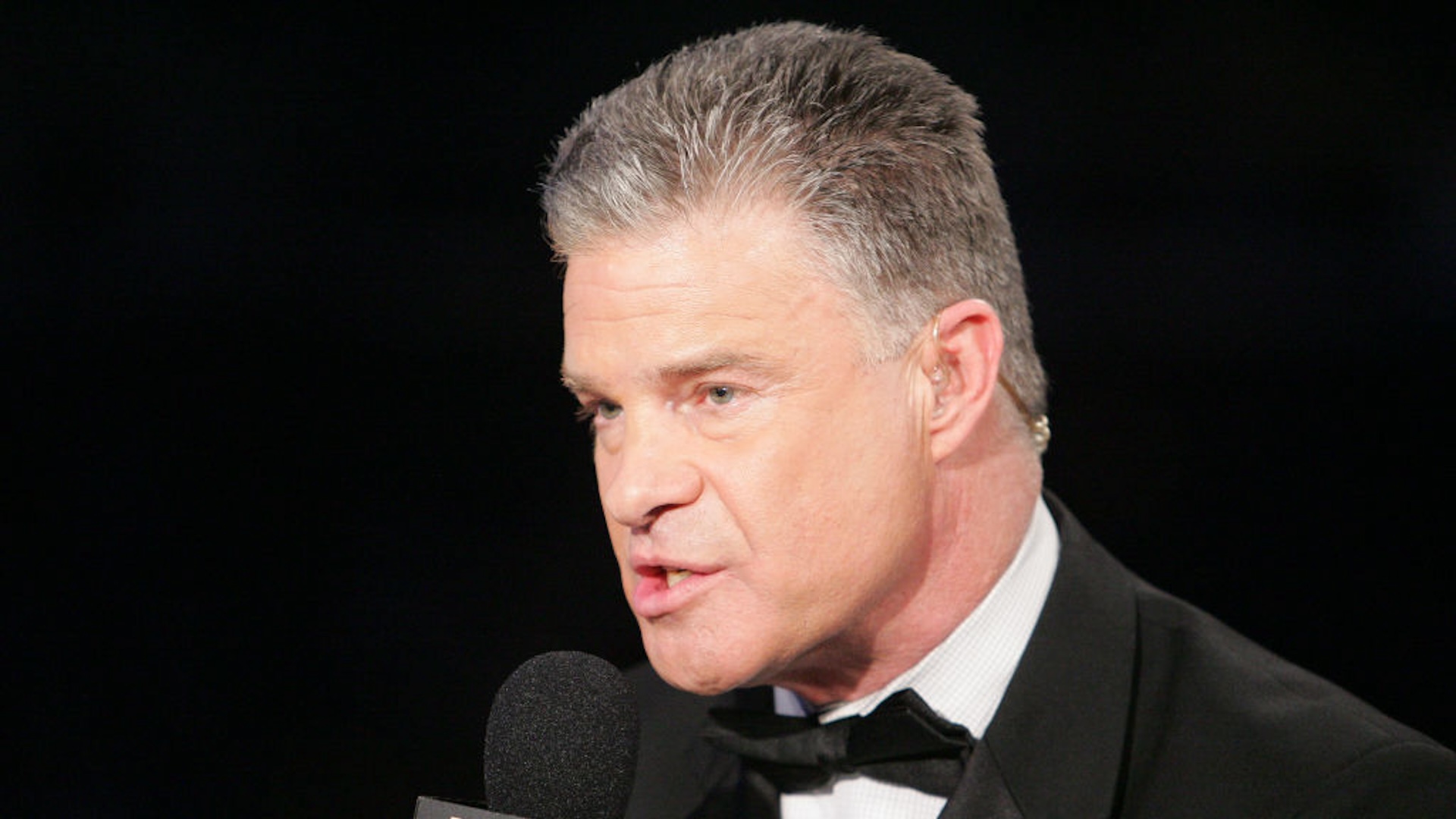

Lampley, newly 76 years old, will enhance the weekend's quaintness by being ringside and behind a microphone for the Friday night fights in Times Square. The Boxing Hall of Fame inductee hasn't given a blow-by-blow fight call since HBO got out of hurt business in 2018. Lampley had worked for the formerly fight-friendly cable station for 31 years.

My conversation with Lampley came via a phone call to his home in North Carolina. His day job nowadays is as a professor in the communications department at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. He teaches storytelling in media. His life in boxing has given him plenty of his own stories to tell. The guy was at the 1964 Cassius Clay–Sonny Liston fight, for chrissakes, in which the young Louisville Lip, days away from introducing himself as Muhammad Ali, shook up the world. Lampley tells about witnessing that piece of history and lots of other entertaining and enviable tales in a memoir, titled It Happened: A Uniquely Lucky Life in Sports Television, that was published last month.

He writes in the book that his fight fandom came about as a way to connect with his father, who had died of cancer when Lampley was just five years old. In December 1955, his recently widowed mother sat him in front of a TV and made him watch Don Dunphy call a Sugar Ray Robinson title bout on NBC's primetime Friday night fights show, The Cavalcade of Sports.

"If your father were still alive," she told him, "this is exactly what you would be doing with him."

Lots of other Americans also did exactly that on Friday nights at the time. In 1950, that weekly boxing program, broadcast from Madison Square Garden, was the seventh most-watched TV show in the country in the annual ratings book. A 1960 Sports Illustrated story on The Cavalcade of Sports as it was being taken off the air said "one out of every five home television sets" had been regularly tuned in.

Lampley, who was born in Carolina but moved with his mom to Miami after his father's death, ended up catching the boxing bug, mostly because he became enamored with Ali in the 1960 Olympics. Rooting for a brash young black guy pleased his socially activist mother and peeved the racist white Southerners he was surrounded by in his neighborhood and at school. His hero worship was complete when Ali came to town to train for the 1964 Liston fight. Lampley, then 14, stalked the local gym where Ali worked out in hopes of seeing his 22-year-old idol, and with lawn-mowing money and financial assistance from his mother got a ticket to the now-iconic heavyweight title bout at the Miami Beach Convention Center. Ali, the 8–1 underdog, humiliated and pounded the champ until Liston sat on his stool and refused to come out for the seventh round. Within a week of taking Liston's belt and baddest-man-on-the-planet mantle, the fighter changed his name to trumpet his Nation of Islam conversion and honor Elijah Muhammad.

The fight young Lampley saw in person had been broadcast live on radio and shown to a limited audience on closed-circuit television, a precursor to today's pay-per-view schemes, at arenas and theaters across the country. But most Americans first watched the history-changing bout two months after it happened on free TV on ABC's new sports show, Wide World of Sports. The New York Times reported at the time that the network brass bought the broadcast rights after the fight realizing the shocking outcome had given it instant-classic status. That episode of Wide World was hosted by Howard Cosell, who would parlay his relationship with Ali into a career as the most famous media man in boxing history. Through a combination of hard work, unique luck, and destiny, Lampley found himself working for that same network and on that very show right after college. And he'd make a little media history of his own at there: Lampley is recognized as the first sideline reporter in football history, a gig he got from ABC bosses in 1974 because they were looking for somebody who still looked like a college student to appeal to young viewers.

Lampley got to refocus on boxing after Cosell very publicly gave up on the sport while working a viciously one-sided 1982 heavyweight fight between Larry Holmes and punching bag Randall "Tex" Cobb. Lampley was paired by ABC with a comparatively stiff boxing sage, Alex Wallau, to pick up Cosell's fight-calling gigs. He's also had runs as a leading voice in tennis, golf, and even surfing broadcasts at various points in his career, plus the sideline football stint. But it's the ringside renown Lampley began earning alongside Wallau, then continued during his decades-long stint as the frontman for HBO's World Championship Boxing programming, that he'll be most remembered for.

The job put him behind a microphone for many of the most momentous bouts of the last half century. Lampley, for example, called Mike Tyson's first televised pro bout, against Jesse Ferguson in February 1986, which ended in the fifth round with an uppercut from the teen titan that exploded Ferguson's nose. "I wanted to drive the nose bone into his brain," Tyson later explained. Lampley was there again with Wallau for Tyson's 25-second destruction of Marvis Frazier (Smokin' Joe's son) in July 1986, the knockout that got even non-boxing fans to start paying attention to this ferocity known as Iron Mike. And, at the other end of the Tyson glory spectrum, Lampley called his fight against James "Buster" Douglas in Tokyo in February 1990, when the unknown challenger KO'd the undefeated and presumably unbeatable Tyson and briefly shook the world as hard as Ali had in Miami in 1964. In the moment, Lampley described Douglas's win as "the biggest upset in the history of heavyweight championship fights," and that call still rings true. Tyson lost his mystique along with his belts that night, and his career never recovered.

Lampley was on the job when George Foreman felled Michael Moorer to win back the heavyweight title at 45 years old in 1994, 20 years after losing it to Ali in the fabled Rumble In the Jungle. Moments after Moorer was counted out and Foreman became the oldest fighter ever to capture the heavyweight belt, Lampley yelled, "It happened! It happened!" That climactic fight call gave his new memoir its title.

Lampley also worked the 2015 Floyd Mayweather–Manny Pacquiao fight, which still ranks as the number one pay-per-view event in sports broadcasting history, with 4.6 million buys.

Along with calling so many iconic fights, Lampley has also been on the mic for some of the sport's worst nights. He worked both of Riddick Bowe's legendarily brutal fights with Andrew Golota. The first, at Madison Square Garden in July 1996, ended in the seventh round when Golota, possibly the most talented heavyweight in the world at that particular moment in time, decided he'd rather hit Bowe in the nutsack again and again and again than be champion. When Golota was rightly disqualified by referee Wayne Kelly for repeated low blows, the crowd and Bowe's corner began a riot. Lampley was protected during the out-of-bounds Garden party by his color commentating partner on the HBO broadcast that night: George Foreman. Lampley also called Bowe-Golota II, in Atlantic City the following December, which again ended with Golota being DQ'd for targeting Bowe's testicles. Not surprisingly, there was no trilogy match.

Lampley was ringside for Bowe's second fight with Evander Holyfield, held in 1993 at an outdoor stadium in Las Vegas; the bout is mostly remembered for the "Fan Man" incident, in which a doofus parachuted into the stadium only to have his chute caught in ringside scaffolding. Bowe's cornermen pounded on the interloper while he was still trapped in his chute.

Both ABC and HBO had always given Lampley the resources to find worthy up-and-coming fighters and introduce them to new generations of boxing fans; that's how he ended up at a teenage Tyson's bouts. But since HBO got out of boxing, no media outlet devotes any energy to telling the fighters' tales. Meanwhile, the UFC has been holding almost weekly televised cards and putting unknown combatants in idol-making reality shows. So MMA, despite being a vastly inferior craft compared to the sweet science, is capturing young American combat sports fans who in previous generations would have surely gravitated toward boxing.

"'Regularly scheduled' is the biggest economic mover in sports," Lampley tells me. "There was a time when I was young when you knew you would see fights on Friday nights and they would be called by Don Dunphy. Boxing has lost that. Other sports have elbowed boxing out of the picture."

But here Lampley is calling a slate of Friday night fights in Times Square, just like Dunphy did not too many blocks down the street at the Garden that Friday night some 60 years ago when he first fell for boxing. He says he's excited and grateful at this point in life to get a chance "to see if I can still do it."

Asked what he thinks will take place, Lampley says, "Some of the most unusual things I ever witnessed took place when the fight was outdoors. So something unusual will happen! Watch it or you'll miss it."

That last line, which Lampley learned in a lifetime in the fight game, is probably as good a selling point as boxing ever had. Walkouts are scheduled to begin at 7:00 p.m.