Investment. Arbitrage. Profits. Losses. Assets. Stocks. Business.

If you don't understand the true essence of those words, then you'll probably need a team of experts to help walk you through ESPN NBA insider Brian Windhorst's latest, because it's a highly complex and brain-addling read. His blog, headlined "Betting against an opponent's future is the NBA's market inefficiency," is about how NBA teams are following highly complex "business-style" modes of thinking, using them to do analytics, and pushing the league to a new frontier that is unrecognizable to old-school fans.

Last season, when the Golden State Warriors -- owned by Joe Lacob, a partner at one of the nation's preeminent venture capital firms -- traded D'Angelo Russell to the Minnesota Timberwolves, the deal was rather nakedly structured around betting against the Wolves' future.The primary assets coming back: the Wolves' first- and second-round picks in the 2021 NBA draft. The Warriors are wagering that the first-rounder would not only be in the lottery of a draft projected to be deep with talent -- Minnesota has missed the playoffs in 15 of the past 16 years -- but that sending Russell would not change that direction.[...]Increasingly, front offices have taken on the role akin to venture capital firms, fund managers or even old-fashioned stockbrokers, spreading wide nets and hoping for one angel investment to hit or simply "shorting" the future outlook of trade partners.

Wow. My head would be spinning if I didn't co-own a small business, but yours probably is, so I can walk you through this. A future draft pick is like a pick in the draft, but it comes in the future. The pick will be higher if the team that traded it to you worse. The Warriors understand this because their owner is a big-brain thinker whose experience in the financial sector allows him to understand concepts like "the future," which nobody in the NBA could do before 2005.

Please read this paragraph twice, I don't want you to miss anything.

"That's why there's a marketplace," one general manager said, "because you have buyers and sellers just like the stock market."

A "buyer" is one who buys things. A "seller" is one who sells things.

Windhorst goes on to explain the case of the Thunder. General Manger Sam Presti has traded away most of his good players for draft picks, acquired bad players on expensive contracts for even more draft picks, and has done his level best to make it so those draft picks come to him as far out in the future as possible, when the aforementioned good players will not making the value of those draft picks worse.

But, of course, that isn't enough -- Presti also built in options. The first-round picks from Houston for Westbrook don't arrive until 2024 and 2026, but Presti asked for a pick swap for the Rockets' pick this upcoming season (top-four protected). In the event of a black swan event -- like, say, Westbrook and Harden demanding trades within a year -- the Thunder had another way to capitalize.

Whoa, a "black swan event"? Is that some sort of bird party? Even I cannot process this, so I reached out to Defector VP of Operations Jasper Wang to have him explain it to me.

PR: What is a black swan event?

JW: A black swan event is supposed to be an EXTREMELY unlikely outcome.

My God. Okay.

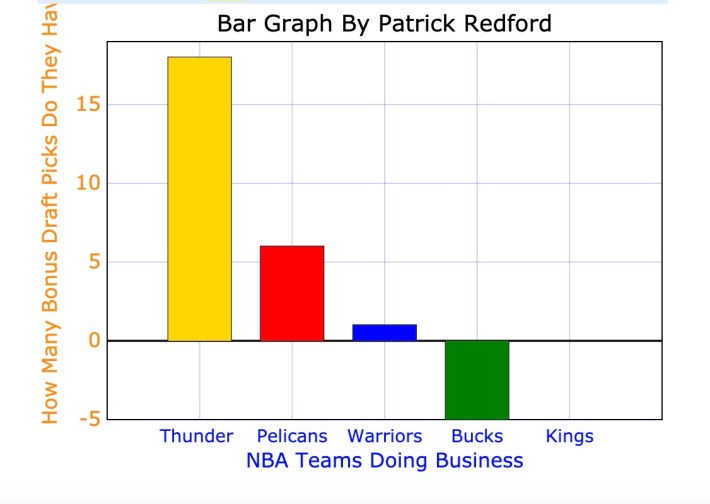

What I am learning from this story is that draft picks are good. Maybe you're a visual learner, so I made a graph to help you wrap your head around this.

The originator of this new way of thinking is of course Sam Hinkie, the former Sixers GM who briefly pretended to work at Stanford. Hinkie worked under two owners from the private equity world (Note: Private equity is like equity but it's private), and he pulled off what Windhorst identifies as the first "short" trade when he extracted a pick and a pick swap from the Sacramento Kings, betting on them to suck shit. You're probably looking for a takeaway for your own life, and here it is: Identify the "Sacramento King" in your life, tell them you'll pay them Tuesday for a hamburger today, and, boom, you're doing business, my friend.